Few people have done more to change the world and have gotten rewarded less for their efforts than Edwin Drake. On August 27, 1859, Drake became the first person in history to successfully drill for oil. Despite his early start, within a few years of his discovery Drake was nearly broke. He had spent most of his money, unsuccessfully, buying up land in search of more oil. Two decades after his revolutionary finding, Drake died with little money to his name. You might hear this and think that Drake was one of the unluckiest people in history, but that’s not the full story.

The only reason Drake was able to find oil in the first place was due to a particularly lucky set of circumstances. Drake had been a railroad conductor most of his career, but was forced to retire due to health issues. It was through a chance meeting at a hotel during his retirement that Drake met George Bissell and Jonathan Eveleth, the two men he would go into business with in the quest to find oil. Bill Bryson tells the story of what happened next:

For more than a year and a half they drilled, but no oil came. By the summer of 1859, Bissell and his partners were out of funds. Reluctantly, they dispatched a letter to Drake instructing him to shut down operations. Before the letter got there, … at a depth of just under seventy feet, Drake and his men hit oil.

Though Drake never made any money off of his oil speculation, in 1872 he was granted an annual pension of $1,500 (50% more than his yearly wage with Bissell/Eveleth) by the state of Pennsylvania for helping to found a new industry.

So, was Edwin Drake lucky or unlucky? Depending on what set of facts you use, you can make either case. Because Drake’s story highlights one of the most overlooked concepts in our lives: the ebb and flow of luck, or what I like to call fickle fortune.

We tend to ignore how often luck changes in our lives and end up extrapolating out our most recent experiences. This explains how one negative event can lead to fear and one positive event can lead to greed. The truth is usually somewhere in the middle, but people and markets don’t behave this way.

Fickle fortune is found everywhere in the investment industry. Just look at the Dow Jones Industrial Average and you will see that not a single company currently in the index was in it 100 years ago. Even the sharpened FAANGs of today will eventually dull and fall out of favor. More importantly, this idea can also be applied to asset classes, not just individual businesses.

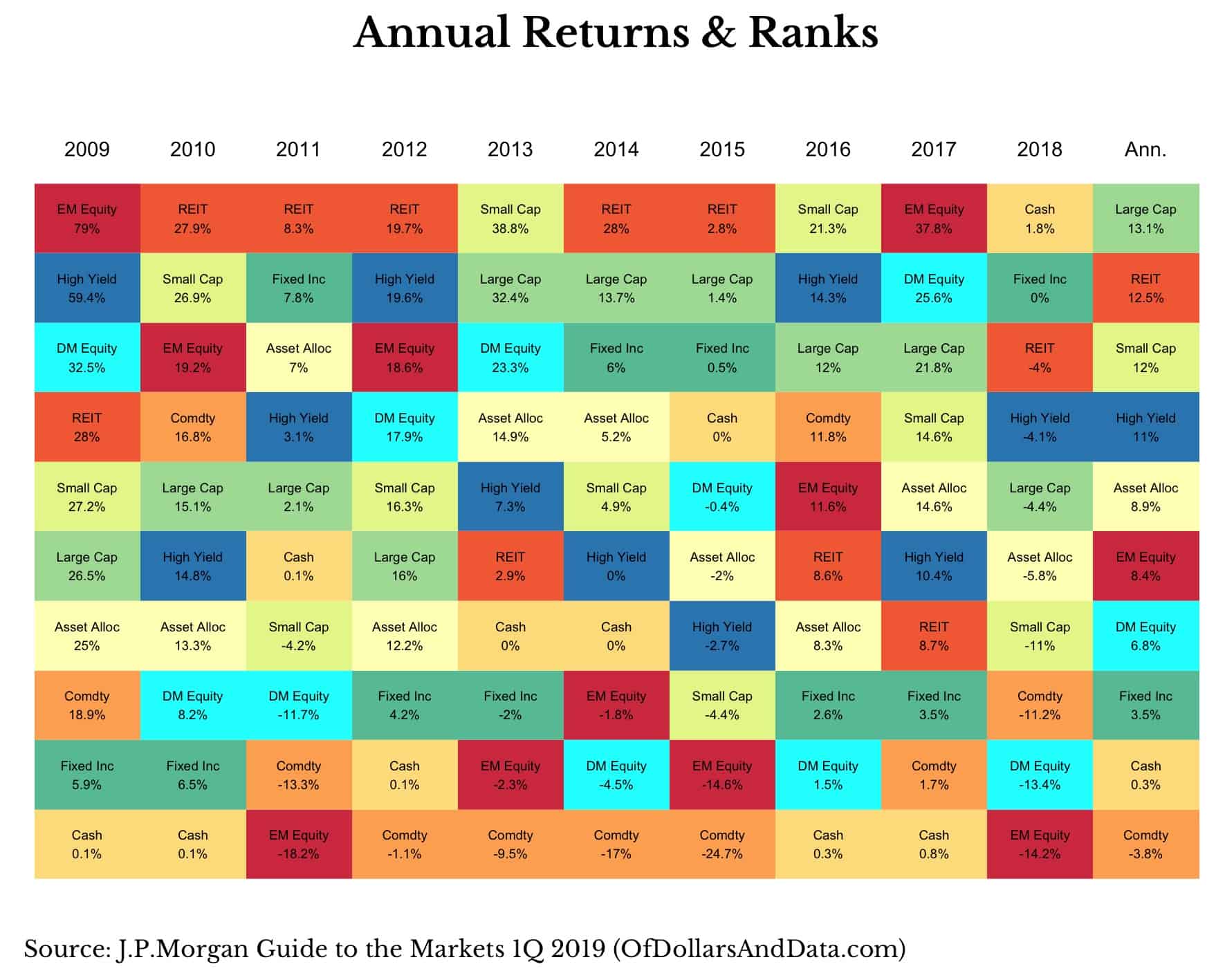

To illustrate this, consider the relative performance of 10 different asset classes over the last 10 years (2009-2018). This performance chart (which is one of Ben Carlson’s favorites) shows the relative ranks and returns of each asset class by year with the annualized return over the 10 years (“Ann.”) at the far right:

The purpose of this chart is to show the variability of relative asset performance over time. As you can see, some years an asset class is near the top and some years it is not. There is no law guaranteeing that long term returns should converge across asset classes, but there is some evidence of mean reversion (at least for equities). As Jason Zweig once stated:

From financial history and from my own experience, I long ago concluded that regression to the mean is the most powerful law in financial physics: Periods of above-average performance are inevitably followed by below-average returns, and bad times inevitably set the stage for surprisingly good performance.

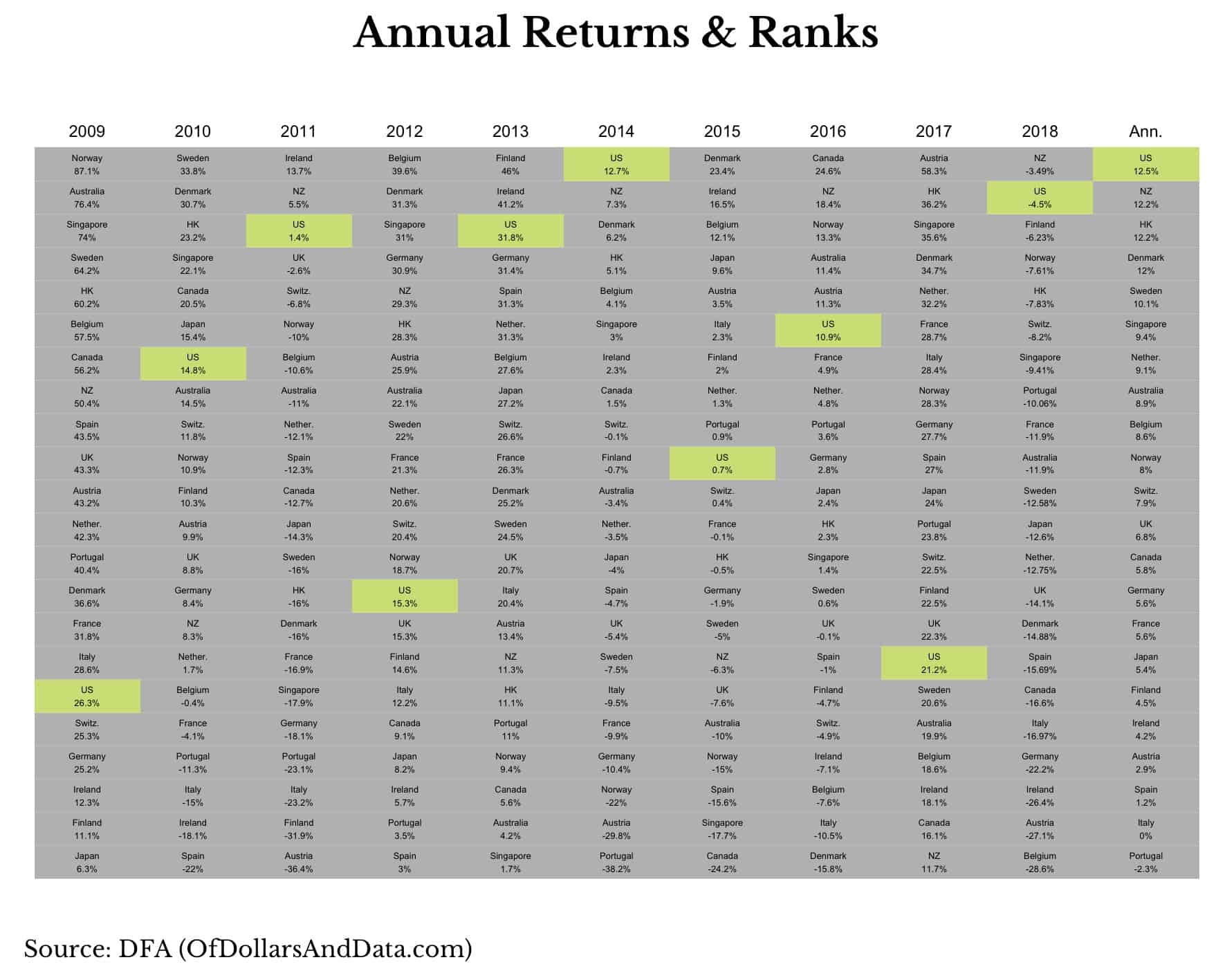

What’s funny about Zweig’s description is how true yet ignored it is by the financial media. All the time I see stories of how asset X is underperforming or asset Y is the hot new thing. These things come and go, yet our society spends so much time discussing minor trends that, many times, will reverse. Consider how the U.S. has outperformed every other developed market over the past 10 years (Click on the image to see it more clearly):

Maybe there is some form of American exceptionalism and the U.S. will continue to be the best performing developed equity market on Earth, or maybe this is just fickle fortune. While I do believe in the future of U.S. equity markets, I doubt the U.S. will be the best performing developed equity market for the next 10 years. If you disagree, consider the wisdom from Matthew 23:12:

For whoever exalts himself will be humbled, and whoever humbles himself will be exalted.

Stay the Course

Last week the investment world lost one of its greatest innovators and thought leaders—Jack Bogle, the founder of Vanguard and the man who popularized the index fund. A lot that has been said about Bogle, but what most interested me were the odds he overcame to revolutionize an industry.

Bogle’s family lost everything in the Great Depression and his father resorted to alcoholism, but this didn’t stop him from working hard and getting into Princeton. Bogle had his first of six heart attacks at age 31 and had a full heart transplant at age 66, but this didn’t tame his vigor when attacking high fees in the mutual fund industry. As Jason Zweig documented, the man faced off with death and opponents throughout his life, but was able to persevere. He had some good luck, but he had lots of bad luck too.

Now consider what lady fortune has done for you. You have probably had some setbacks. Some things weren’t fair. However, you have probably also had good luck too. Maybe you were born in a developed country, or you had loving parents, or you were born smarter than average. I don’t know your history, but I am confident that if you look back you will find some chance events that benefited you in profound ways.

However, life isn’t about the hand we are dealt, it’s about how we play it. It’s about how we react to what the world throws at us. This is true in investing and everywhere else. As Mr. Bogle would say, “Stay the course.” So, stay the course, my friends, and you may never have to worry about fickle fortune again. Thank you for reading!

If you liked this post, consider signing up for my newsletter.

This is post 108. Any code I have related to this post can be found here with the same numbering: https://github.com/nmaggiulli/of-dollars-and-data