In the late 1970s the view in the publishing world was that an author should never produce more than one book a year. The thinking was that publishing more than one book a year would dilute the brand name of the author.

However, this was a bit of a problem for Stephen King, who was writing books at a rate of two per year. Instead of slowing down, King decided to publish his additional works under the pen name of Richard Bachman.

Over the next few years, every book King published sold millions, while Richard Bachman remained relatively unknown. King was a legend. Bachman a nobody.

However, this all changed when a book store clerk in Washington, D.C. named Steve Brown noticed the similarity of writing styles between King and Bachman. After being confronted with the evidence, King confessed and agreed to an interview with Brown a few weeks later.

The Click Moment: Seizing Opportunity in an Unpredictable World tells the story of what happened next:

In 1986, once the secret was out, King re-released all of Bachman’s published works under his real name and they skyrocketed up bestseller lists. The first run of Thinner had sold 28,000 copies — the most of any Bachman book and above average for an author. The moment it became known that Richard Bachman was Stephen King, however, the Bachman books took off with sales quickly reaching 3 million copies.

This phenomenon isn’t exclusive to Stephen King either. J.K. Rowling published a book called The Cuckoo’s Calling under the pen name Robert Galbraith only to be outed by someone performing advanced text analysis with a computer. Shortly after the public discovered Galbraith was Rowling, The Cuckoo’s Calling increased in sales by over 150,000% shooting to the #3 on Amazon’s bestseller list after previously being ranked 4,709th.

Both King and Rowling’s foray into undercover writing reveals a harsh truth about success and social status — winners keep winning. This idea is formally known as cumulative advantage, or the Matthew effect, and explains how those who start with an advantage relative to others can retain that advantage over long periods of time.

This effect has also been shown to describe how music gets popular, but applies to any domain that can result in fame or social status. I discovered this concept by reading Michael Mauboussin’s The Success Equation where he writes:

The Matthew effect explains how two people can start in nearly the same place and end up worlds apart. In these kinds of systems, initial conditions matter. And as time goes on, they matter more and more.

This explains how King and Rowling sell millions while Bachman and Galbraith don’t, despite being of similar quality. While I find these anecdotes and others useful, we can illustrate cumulative advantage using a simple simulation.

To start, imagine we have 400 marbles in a bag equally spread across 4 different colors (i.e. 100 black, 100 blue, 100 red, 100 green). Now we draw a color at random and add 1 additional marble of that same color back to the bag.

So, if we drew a green marble in the first round, we would have 101 green marbles, 100 red, 100 black, and 100 blue in the bag at the end of the first round. We would keep drawing marbles and adding the 1 additional marble to the bag over 40 rounds and then end the game.

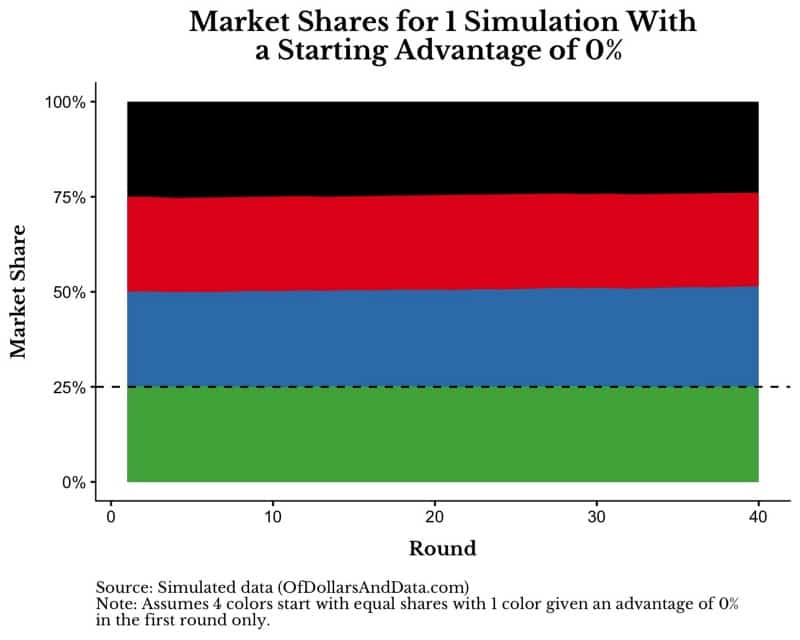

One such simulation of this game could look like this (Note: the colors represent the marble market shares in each round):

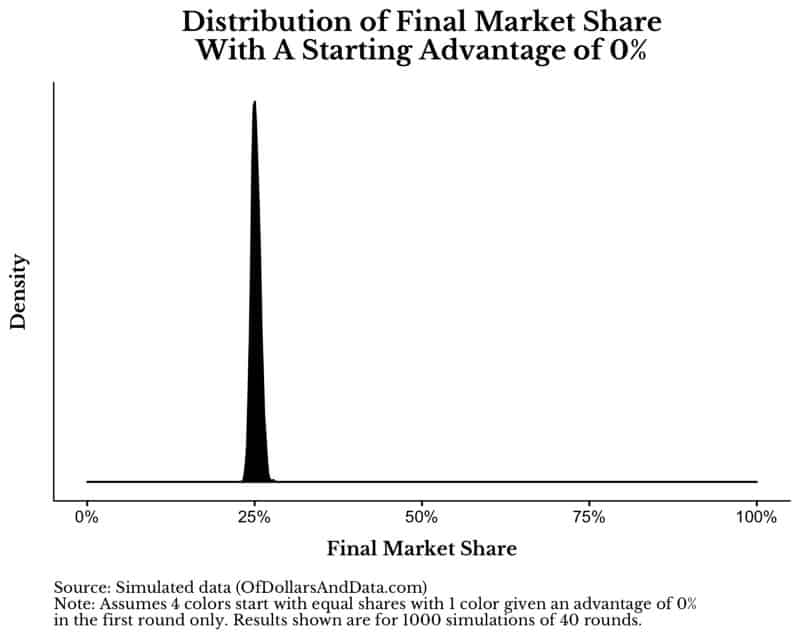

As you can see, there is very little variation in market shares because the reward size (1 marble) is small relative to the total number of starting marbles (400). The distribution of the market share at round 40 (“final market share”) across 1,000 simulations for any one color could look like this:

As we expect, the mean final market share with no starting advantage is 25% with a very small standard deviation.

However, what if we rigged the game such that we gave a particular color an advantage to start? For example, instead of giving 1 additional marble in each round, we give 100 additional marbles in each round.

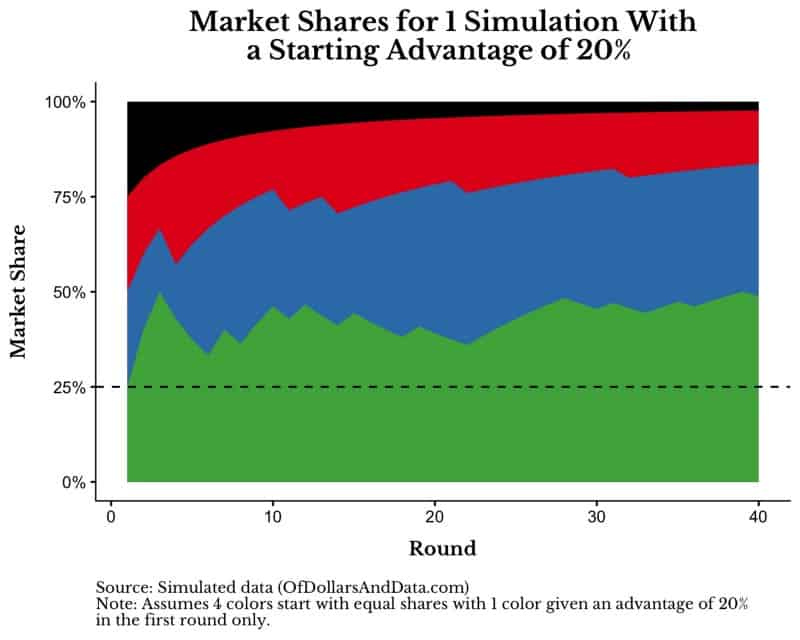

If we did this, one color would have a market share of 40% (200/500) while the remaining colors had a share 20% (100/500) starting round 2. This is a starting advantage of 20% (40% — 20%) in market share. One such simulation, where green is given the starting advantage, could look like this:

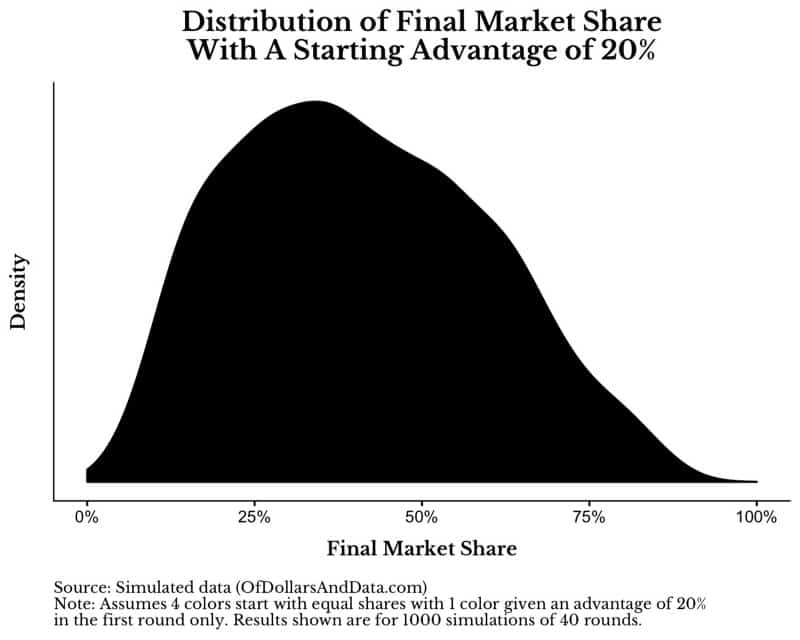

As you can see, the green color starts with a huge lead and never gives it up over time. Across 1,000 simulations like the one above, the distribution of final market share for the advantaged color (i.e. green) could look like this:

With that 20% initial advantage, the final market share increases significantly. What is even more amazing is that this advantage was only given in the first round and everything after that was left to chance. If we were to keep increasing the size of the starting advantage, the distribution of final market shares would continue to increase as well:

The purpose of this simulation is to demonstrate how important starting conditions are when determining long term outcomes. Instead of marbles though it could be wealth, or popularity, or book sales. And most of these outcomes are greatly influenced by chance events.

We like to think in America that most things come down to hard work, but a few lucky (or unlucky) breaks early on can have lasting effects over decades. If we look at luck in this way, it can change the way you view your life…

The Worlds We Simulate

Think about the story you tell yourself about yourself. In all the lives you could be living, in all of the worlds you could simulate, how much did luck play a role in this one?

Have you gotten more than your fair share? Have you had to deal with more struggles than most?

I ask you this question because accepting luck as a primary determinant in your life is one of the most freeing ways to view the world. Why?

Because when you realize the magnitude of happenstance and serendipity in your life, you can stop judging yourself on your outcomes and start focusing on your efforts. It’s the only thing you can control.

I know this because I have had far more luck than most. If I ran the world 1,000 times over, in less than a handful would I be where I am today.

Most lower-middle class kids growing up with divorced parents don’t get the chance to get a full ride to a top university. And even fewer ever find their passion and get to do it everyday. However, I’ve always tried to work hard and that’s where I get my satisfaction.

So don’t let good luck put you on a pedestal, but don’t let bad luck knock you down either. Because for every Stephen King there is a Richard Bachman that never saw the light of day. Yes, some of us are born with more advantages than others and some of us are born with less, but you should never let that define how hard you try.

So, best of luck from Of Dollars And Data and thank you for reading!

If you liked this post, consider signing up for my newsletter.

This is post 71. Any code I have related to this post can be found here with the same numbering: https://github.com/nmaggiulli/of-dollars-and-data