On the surface, the life of Christina Santhouse does not seem particularly remarkable. She has a master’s degree in speech pathology. She owns her own home. She is married. But, there is something different about Christina — she only has half a brain.

At the age of 7, Christina was diagnosed with Rasmussen’s encephalitis, a rare neurological condition characterized by frequent seizures. As a result, it was recommended that she undergo a hemispherectomy where half of her brain would be removed. The procedure was performed in 1996 when Christina was 8 years old by the now famous politician/neurosurgeon Ben Carson. As a result of the surgery, Christina lost most of the motor skills on the left side of her body, but today she has the ability to walk and lives a mostly normal life.

I tell this story because it illustrates how amazing natural systems can be at adapting to change and thriving in the face of uncertainty. You might assume that after losing half a brain, most individuals would be completely non-functional, but you would be wrong. Patients undergoing a hemispherectomy do experience changed motor skills, but one study suggests that cognitive changes were not major.

This is what makes life so amazing. It explains why we can live with only one kidney though we are born with two. It explains how our brains can adapt to changes (i.e. neuroplasticity) even when we are missing an entire hemisphere. If you think about it, this all boils down to natural systems relying on redundancy to increase the chance of survival. In other words, nature has a trick up it’s sleeve — a margin of safety.

When it comes to investing, having a margin of safety increases the chance of financial survival and is arguably the most important (and difficult) investment rule of all. To illustrate this, consider the following question:

What is the most important piece of information when it comes to buying a stock?

Is it management? Growth prospects? Profitability? No, no, and no.

The most important piece of information when buying a stock (or any asset) is — the price you pay.

That’s right. Even with bad management, terrible growth, and bad profitability, there exists some price, possibly a negative price (i.e. I pay you to own it), at which every asset would be a good investment. All the other aspects of an investment will fail you if you pay the wrong price.

This is the fundamental tenet of value investing and the data to back it is extensive. Just watch this talk on global value by Meb Faber and the evidence for value investing will crush any doubt you may have. If you still don’t believe me, consider what Warren Buffet said to Brent Beshore over dinner last year:

Price is my due diligence.

This simple yet profound idea is the essence behind a margin of safety. It implies that you can still profit from an investment, even after getting some bad luck, if you can get a good enough price. Therefore, if you think the intrinsic value of a company is $100 a share and you get it for $50, you have quite a bit of wiggle room for bad things to happen (i.e. lawsuits, bad management, a Kylie Jenner tweet, etc.) so you can recover.

Dan Rasmussen recently wrote an incredible piece on his experience in private equity that backs this idea further:

One PE firm did just such an analysis and found that over 50 percent of deals done at valuations of more than 10x EBITDA lost money and that the aggregate multiple of money was barely over 1.0x (i.e., for every dollar invested, only slightly more than one dollar was returned to investors).

Once again, higher purchase prices imply lower returns.

You may be thinking that price only matters for the first few years, but over longer periods the price paid shouldn’t matter. I even implied this when I previously discussed valuations and showed how annualized real returns converged over longer time periods for the U.S. stock market. However, my friend Jake pointed out how even small differences in annual returns can make huge dollar differences when compounded.

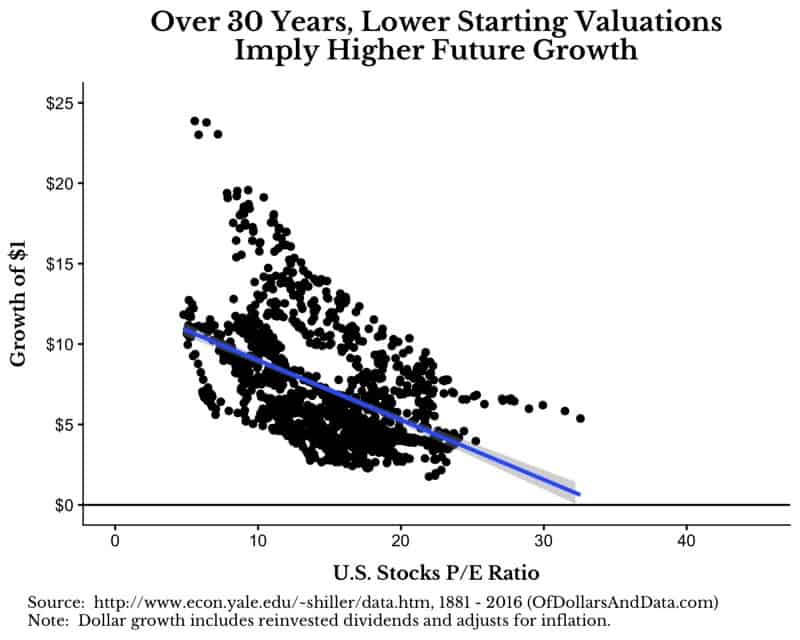

I looked into this further and realized that he was completely right. If you look at every 30 year period for the U.S. stock market from 1881 onward you will see that lower starting valuations (as measured by Shiller’s CAPE) imply higher future dollar growth. This chart shows the growth of $1 over 30 years in the U.S. stock market on the y-axis and the initial valuation on the x-axis:

As you can see, there is a clear negative relationship between initial valuation and future dollar growth. And just for fun, you can see this animated starting with the total growth over 5 years and progressing to a period of 30 years. Note that the green points represent positive total dollar growth and red points are negative growth:

While valuations aren’t completely predictive, they do seem to matter.

So, value investing must be killing it right now, right?

Nope. It is either underperforming or doing okay, but it depends on how you measure it. Even when you Google it you get this:

And this is why value investing, despite being arguably the most important investing rule across all space and time, is also one of the most difficult…

Ignorance is Easier than Catching Falling Knives

Despite all of the evidence I just discussed about how much purchase price matters in investing, I still think you should mostly ignore this advice if you are an average retail investor. Why? Buying when things are cheap requires you to time the market to some extent. This is difficult, because you could buy when you think something is cheap…and then it gets far cheaper. In the Meb Faber value talk he makes the following joke that illustrates this point:

What do you call a market that is down 90%?

That’s a market that was down 80%, then proceeded to go down 50% more.

Trying to buy an investment as it is bottoming is known as “catching a falling knife”, and it can be both difficult and scary. So what should you do instead of exclusively trying to buy cheap? Consider the following:

- Dollar cost average, or as I love to say, “Just Keep Buying.” While this is not optimal mathematically, since you sometimes buy assets at inflated valuations, behaviorally it is by far the best solution I know for the average retail investor. Buying consistently is an ignorant approach to market valuations that is far easier than catching a falling knife.

- Add a value tilt to your equity allocation. There are lots of value ETFs and mutual funds out there that can give you some value exposure. I wouldn’t put too much of my total equity in this though as value is known to go through periods of underperformance, which can make holding the investment difficult.

If any of this got you interested in learning more about value investing, I recommend the following books to start:

- The Intelligent Investor (Benjamin Graham + Jason Zweig)

- The Education of A Value Investor (Guy Spier)

- Security Analysis (Benjamin Graham + David L. Dodd)

- Margin of Safety (Seth Klarman) This book is out of print, difficult to find, and currently sells for $700 for a used copy. Best of luck if you find one.

Thank you for reading!

If you liked this post, consider signing up for my newsletter.

This is post 61. Any code I have related to this post can be found here with the same numbering: https://github.com/nmaggiulli/of-dollars-and-data