Between 1985 and 2012, a total of 84,350 pension plans disappeared within the United States. In 1970, 45% of private sector workers had a defined benefit pension plan. Today it’s only 15%.

Could the same thing happen to the 401(k)?

It might seem like a crazy question to ask given the widespread adoption of the 401(k), but imagine I had asked the same thing about pensions back in 1970. This would’ve seemed like a crazy idea at the time too. I would’ve heard things like, “Pensions are the backbone of the American retirement system,” and “How could we live without them?”

But guess what? Things changed and we found a way. I have a feeling that a similar change is on the horizon today when it comes to 401(k)s in America. With the rise of AI/LLMs, the future of human labor has never been more uncertain. And with this added uncertainty, do we need to rethink how we save for retirement?

Before we answer that question, let’s briefly review what almost killed the pension and how the Congress tried to fix it.

What Almost Killed the Pension (and how ERISA fixed it)

In December 1963, the Studebaker-Packard Corporation closed down a plant in South Bend, Indiana. Normally, such an action wouldn’t have caused much of a stir, but Studebaker had a sizable defined benefit plan covering thousands of its workers. Following the plant’s closure, Studebaker “terminated the retirement plan for hourly workers” and defaulted on all its pension obligations. This article from the Journal of Accountancy noted the chaos that ensued shortly thereafter:

At the time, the [Studebaker] plan covered roughly 10,500 workers, 3,600 of whom had already retired and who received their full benefits when the plan was terminated. Four thousand employees between the ages of 40 and 59 received approximately 15 cents for each dollar of benefit they were owed. The average age of this group of workers was 52 years with an average of 23 years of service. The remaining 2,900 employees, who all had less than 10 years of service, received nothing.

Despite the financial fallout from the Studebaker pension failure, nothing changed in the years that followed. It wasn’t until a NBC documentary titled Pensions: The Broken Promise aired in 1972 that the national mood began to shift on pensions. The documentary highlighted the flaws in the U.S. pension system and interviewed individuals who had been deprived of their benefits.

The popularity of the documentary and the public outcry that followed pushed the U.S. government to begin working on a solution. Two years later, the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (“ERISA”) was passed and signed into law in 1974.

ERISA fundamentally changed how private-sector retirement plans were regulated in the U.S. Following the passage of ERISA, every private sector retirement plan had to follow certain rules regarding funding, benefits, vesting schedules, and much more. ERISA also created the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (“PBGC”) to be a government guarantor of private pensions. The PBGC ensured that employees with pensions would receive a minimum amount of benefits in the event a plan failed.

Before ERISA, employees had little to no protections regarding their retirement benefits. They could be promised benefits, but receive nothing. They could lose benefits for having a short stint away from work (e.g. due to a medical issue). Employers could even fire employees without cause right before they were eligible to receive benefits just to save money. The goal of ERISA legislation was to shift the power balance back into employees’ hands and protect their retirement benefits.

Despite the progress achieved by ERISA, within a decade pensions began disappearing from the American workplace. The cause? Defined contribution plans, namely the 401(k).

With the creation of the 401(k) in 1978, employers were able to shift the risk of retirement planning onto their employees. Rather than control and manage the investments themselves, the 401k made it so that employees had to make these decisions. Employers just had to help administer the plans. This was much easier and less risky than the defined benefit pension plans that came before them.

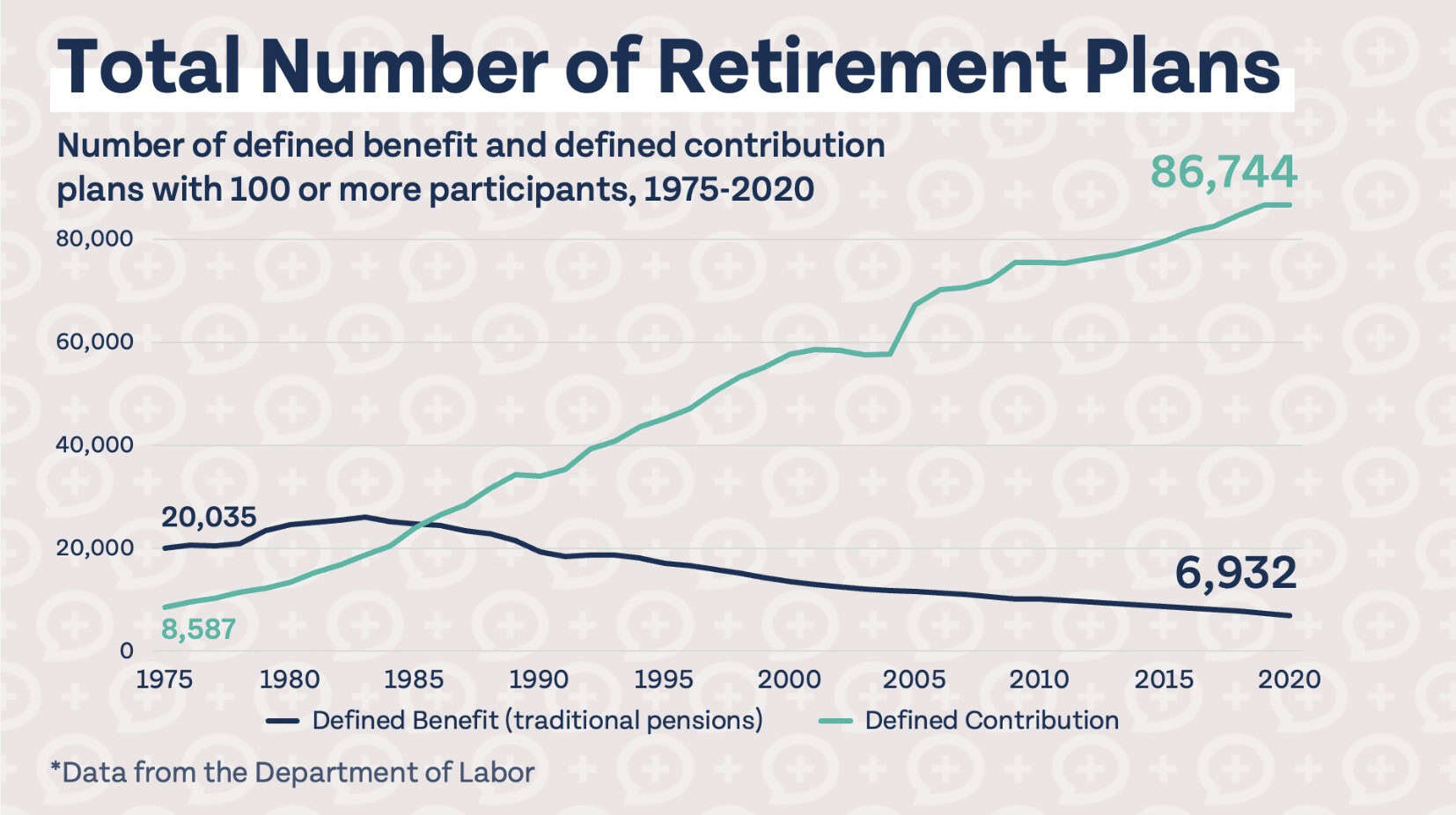

The chart below from The Money Guy Show illustrates this shift from defined benefit to defined contribution plans in the U.S. over time:

With the rise of defined contribution retirement plans, it seems like ERISA solved the retirement problem in America.

But, will this hold true in the future? Or is the 401(k) just the pension plan of the modern era?

Is the 401(k) Next on the Chopping Block?

The downfall of the defined benefit plan among employers makes sense. After all, which company wants to get into the investment management business on behalf of its employees? Exactly. But, when it comes to defined contribution plans, there seems to be no similar kind of pressure.

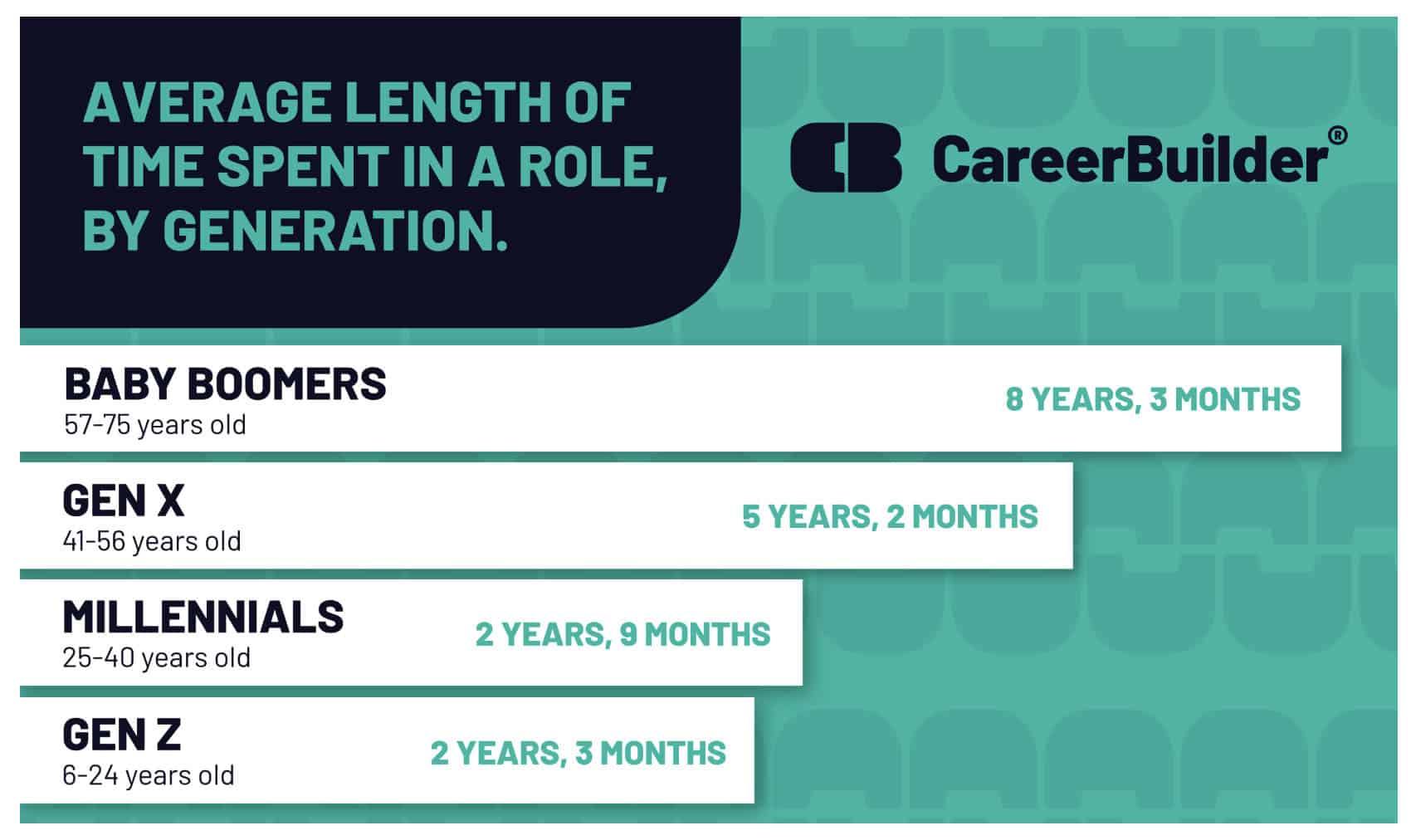

That’s true…for now. But the labor market is changing. We no longer live in a world where you work the same job for 40 years or even a few jobs for a few decades each. As this Career Builder chart illustrates, there’s more job hopping than ever before among the youngest generations:

Of course, some of this is an artifact of age itself. After all, we would expect younger folks to do some job hopping until they found a role they liked, right?

But this isn’t the full story. Because the data suggests that workers have also been quitting their jobs at much higher rates. According to FRED, the share of workers who quit their jobs hit an all-time high in 2022. This was especially true among younger workers. As Forbes noted, “Over 22% of workers ages 20 and older spent a year or less at their jobs in 2022.”

And when people switch jobs they typically lose out on some 401(k) vesting due to the typical multi-year vesting schedules. Even when this isn’t the case, job hoppers still have to deal with future rollovers to access their money. When you combine the increased job switching, the extended vesting schedules, and the hassles associated with rollovers, you can see why the 401(k) doesn’t look as attractive as it used to be.

But, what really makes the 401(k) less appealing today is the uncertainty around the future of work itself. OpenAI recently released a model called Deep Research which can scour the web and write high-quality research reports in minutes. Some are saying that Deep Research (or its successors) will eliminate the need for interns and other junior roles altogether.

If this is even partially true, imagine what the job market will look like for recent college graduates. Do you really want to lock money away for 35 years if you don’t know what the job market will look like in 35 months? Where does a 401(k) fit into a world where work is far less stable than it used to be?

While I don’t know the answers to these questions, I will say that most peoples’ jobs are safe for now. I can say this with confidence because I’ve used LLMs quite a bit. I bet you have too. We all know they are useful, but we also know that they have a fatal flaw—they hallucinate too much. They either make stuff up or produce the most basic errors.

For example, someone asked Deep Research to give it a list of all the players on each NBA team that were at least 30 years old. They found that:

- Deep Research produced the correct list for only 6 out of 30 teams (20%).

- It only identified 59% of the over-30 players on each team.

- For 60% of teams, it named a player not on the team.

While this technology probably saved some time on this project, a human was still required to check the output. This wasn’t a difficult exercise, just a time-consuming one, yet Deep Research couldn’t pull it off.

So while our jobs aren’t at risk for the time being, I still understand the plight of today’s young workers. With everything going on, is it unreasonable for young people to question the usefulness of a 401(k)? I don’t think so. With all the uncertainty around the future of work, I wouldn’t be surprised if fewer employees ask for (and fewer employers provide) these kinds of accounts in the future.

Note that I am not saying that there is something wrong with these accounts. Not at all. If you have the opportunity to get an employer match on tax-free contributions, take it. However, if you’re young, contributing above the match seems riskier than ever.

Lastly, none of this advice applies to anyone who already has considerable savings in a 401(k) or other retirement account. If you made it onto the ship and have already set sail toward retirement island, I don’t think you have much to worry about.

But for those still waiting at the dock, there’s a storm on the horizon and I’m not sure whether these old “ships” will withstand it. Only time will tell.

Happy investing and thank you for reading.

If you liked this post, consider signing up for my newsletter.

This is post 438. Any code I have related to this post can be found here with the same numbering: https://github.com/nmaggiulli/of-dollars-and-data