Roughly 60 miles east of Portland, Mount Hood is the most visited snow covered peak in America. Despite rising 11,240 feet into the skies of northern Oregon, it is considered a “beginner’s mountain” with over 10,000 climbers reaching the summit each year. As Laurence Gonzales stated in Deep Survival:

One difficulty is that the standard route up (and down) Mount Hood is not technical. It’s more of a hike on a steep snow field. On a good day, you can walk it without crampons, snap some pictures on the summit, and be back at the Timberline Lodge ski resort for New Zealand fire-broiled spicy loin lamb chops.

However, on May 30, 2002, Bill Ward and his 3 man climbing crew would learn that the term “beginner’s mountain” was all too deceptive. The four man team was descending the mountain in working order. Ward, the most experienced climber, was at the top, followed by the rest of his team, each man separated by 35 feet of rope between himself and the next climber. The system was well thought out and would work, as long as Ward (the top man) didn’t fall. However, it had rained the previous night and now the slopes were covered in ice and slush, making it easy to fall and hard to stop.

Harry Slutter, the lowest man on the rope, was looking down when he saw a blur out of the corner of his vision. Ward had fallen. In the course of the next few seconds, the force from the rope yanked Slutter and his fellow teammates down the mountain into the crevasse below. Unfortunately, in their free fall, they entangled themselves with other climbers who were also on the slopes. When it was all over, three climbers (including Ward) were killed, and four others had been injured.

Remember, Bill Ward was an experienced climber and Mount Hood was a “beginner’s mountain.” It was easy in theory, but difficult in practice. This idea can also be applied to many other areas of life as well:

- Diet and exercise? Easy in theory, difficult in practice.

- Meditation (i.e. sit and stop thinking)? Easy in theory, difficult in practice.

- Buy and hold investing? The same.

And that’s what I am here to talk about today — buy and hold. The most repeated investing advice on the planet, which I support, is still one of the most difficult to follow. Why? Because simple catchphrases cannot overcome the social, economic, and psychological forces that markets impose on you during panics. Don’t believe me? Let’s do a little thought experiment…

Imagine the S&P 500 has fallen by 30% since its peak a few months prior and your spouse just lost their job. Don’t worry. Buy and hold, right?

Months go by and now the market is down 40%. Your spouse says to you, “Honey, we need to stop this. Think about our children’s future.” As this happens, one of your closest friends brags about how he sold when the market was down only 15%. CNBC reports this is the worst financial crisis of the modern era. You’re still buying and holding, yes?

Another few months go by and the market is down 50% from its peak. Your company lays off workers, but, thankfully, your job is spared. Hundred year old institutions are failing as household names disappear into thin air. Your 6 months of emergency savings is approaching zero, slimming by the day. Your spouse starts to connect dots that weren’t connected before and comes to the false conclusion that you have always been reckless. This time your spouse approaches you more urgently, “Honey, if you don’t do something, I don’t know if I can do this anymore. I can’t live like this. We are almost ruined.”

This is what financial hell is really like. It’s not just you in a vacuum with the numbers trying to keep yourself sane. It’s your partner, your friends, the media, your children, your coworkers. They all play a part in this. Slowly adding pressure points. Slowly degrading your emotional stability. Like an iron maiden for your mind.

Maybe you think you can resist these forces, but so does everyone else. Consider this: how many investors buy stocks thinking they will sell at the bottom? NONE. No one thinks they will be the one to crack. No one thinks they are going to make bad future financial decisions, including you and me. But, somehow many of us still do.

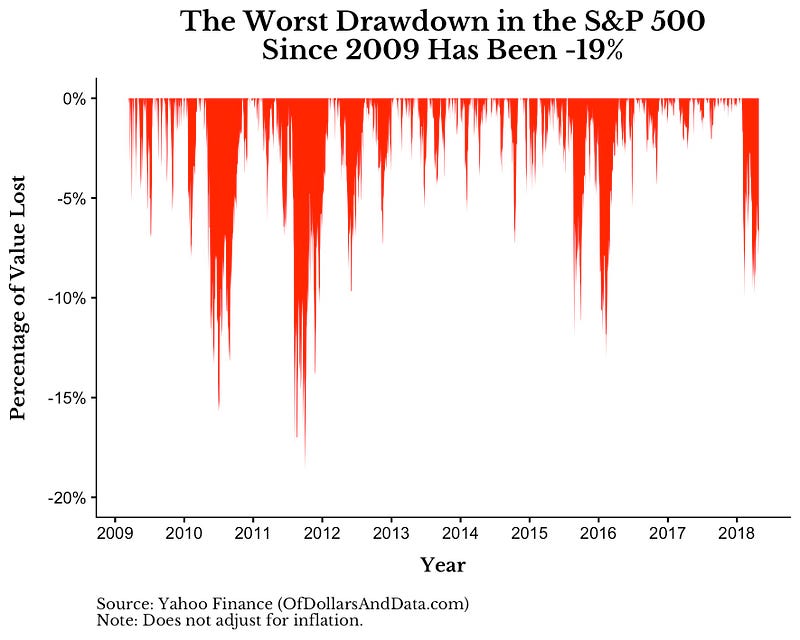

Even now you may think you can do buy and hold well. However, if you have only been investing since the end of the financial crisis (like me) you haven’t seen much action. In fact, since 2009 it’s been a virtual cakewalk with the worst drawdown being only -19%:

The problem is that being down 19% is not that bad. In a typical year, the max intra-year drawdown for the Dow is 12.8%. This means that we should expect the market to be down 10–15% from its peak at some point in any given year. So while you may have been able to “buy and hold” the market over the last 9 years without a problem, if the social, economic, and psychological pressures start mounting, you may be in trouble.

So what’s the solution? Get a good financial advisor. It may seem silly to you, as it once seemed to me. You’re smart. You may even know the math better than most of them, so what could they offer you? They offer a behavioral crutch to save you from yourself. They provide a path forward when the future could not seem less clear. That’s what your paying for. You are giving up 50 basis points a year now to save thousands of basis points when the game gets tough.

The Game

I like to think about investing as a big game. Everyone is holding on. However, everyone has different risk preferences. As soon as markets fall by 5%, the weakest hands say no and get out. By 10%, more crumble under the pressure and leave. This keeps going — 20%, 40%, 60%, etc. It’s all about who will hold (and possibly buy more) and who will fold.

When an investor becomes financially educated, in theory, they may shift their risk preferences slightly so they won’t fold as easily. Whereas before they would sell at a 10% decline, maybe now they can hold until a 20% drop in markets. The problem is, this is a relative game. If everyone believes the same thing (i.e. “buy the dip”, “HODL”, etc.), then all the players preferences are shifted such that the old 10% drawdown is the new 20% drawdown. You really have done little to help yourself.

This is where the advisor adds value. You outsource your ability “to hold” and the portfolio construction to your advisor so that you can keep playing the game and reduce the probability of larger drawdowns altogether. Of course, getting the right financial advisor is easy in theory, but difficult in practice. Good luck with “the game” and thank you for reading!

If you liked this post, consider signing up for my newsletter.

This is post 74. Any code I have related to this post can be found here with the same numbering: https://github.com/nmaggiulli/of-dollars-and-data