This week I want to illustrate how you can ensure your financial soundness during the next crisis by having ample liquidity. But first, let’s start with a story:

“But everything was not fine. Long-Term, which had calculated with such mathematical certainty that it was unlikely to lose more than $35 million on any single day, had just dropped $553 million — 15 percent of its capital — on that one Friday in August 1998. It had started the year with $4.67 billion. Suddenly, it was down to $2.9 billion. Since April, it had lost more than a third of its equity.”

–When Genius Failed: The Rise and Fall of Long Term Capital Management, Roger Lowenstein

The above passage illustrates the beginning of one of the greatest downfalls in hedge fund history — the fall of Long Term Capital Management (LTCM). Despite the spectacular downfall, it was how Warren Buffett responded to the situation that can teach us an important lesson about the power of liquidity.

Before we continue that story, let’s quickly define liquidity so we are all on the same page. Liquidity is a measure of how quickly an asset can be bought or sold without altering the asset’s price. Most of the time, most markets are highly liquid and assets can be bought and sold without issue. However, during a panic, buyers flee, prices plummet, and liquid assets quickly become illiquid. Therefore, having liquidity as an investor means to hold assets that can be easily sold at stable prices.

In the case of LTCM’s decline, their bets on bond spreads became highly illiquid and they continued to lose money as buyers were nowhere to be found. LTCM’s partners realized that they needed cash reserves to hold them over until the financial panic had passed and liquidity resumed. Enter Warren Buffett.

How does Buffett get involved in this fiasco? A few of the bankers involved in helping LTCM contact Buffett because they know he has something that no one else has: money.

In particular, Buffett agrees that he can front LTCM the $3 billion in capital they require to survive the financial storm, but for a price. Buffett wants all of LTCM’s assets for $250 million. Yes, the same assets that were once worth ~$4.67 billion now have an offer price of $250 million. At the time of Buffett’s proposal, LTCM had roughly $555 million in equity remaining, but Buffett’s offer stood at $250 million.

Though Buffett’s deal did not go through due to a legal technicality, it likely would have. This illustrates the power of liquidity during market downturns. When everyone is panicking and no one is willing to buy, a buyer can dictate incredibly low prices.

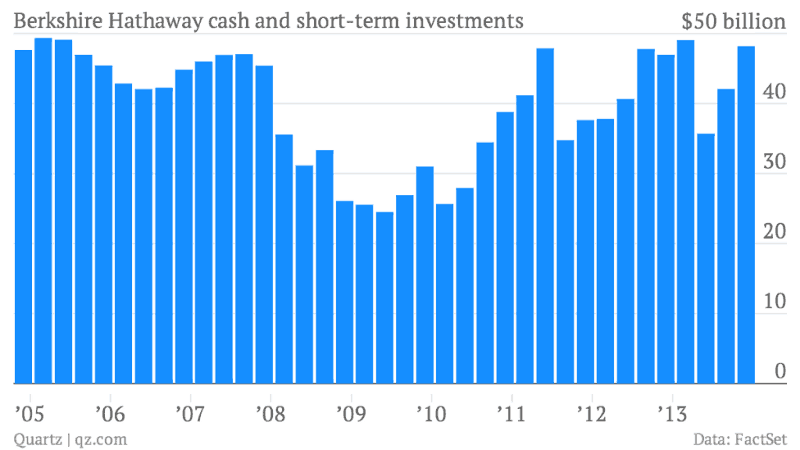

The funny thing is that Warren Buffett does this all of the time. He has a track record of buying companies or lending money when the investment environment looked darkest. For example, Buffett famously aided Goldman Sachs during the financial crisis when he supplied them with cash for shares of Goldman’s stock. Buffett’s final profit ended up being over $15 a second over a 5 year investment period! Looking at Berkshire Hathaway’s cash position during the financial crisis, we see a sharp decrease in cash holdings as Buffett buys in (the chart is from this article):

This demonstrates how Buffett uses his liquidity when the right opportunity presents itself (i.e. sellers become desperate).

Despite his folksy charm, Buffett remains a full-fledged capitalist who wants a cheap deal. Buffett summarizes this part of his investment philosophy beautifully with a quote about baseball:

The stock market is a no-called-strike game. You don’t have to swing at everything — you can wait for your pitch.

And that’s what he does. He waits and waits for the right pitch. Fun fact: Berkshire’s current cash position is the highest it has ever been at $96.5 billion, as of March 31, 2017.

How You Can Use Liquidity To Your Advantage

Though you will likely never have Warren Buffett’s level of liquidity or his business experience to time market purchases, you still can use liquidity to your advantage during future panics. To do this, you should not view liquidity as a way to buy more assets at low prices, but as a way to prevent yourself from selling your assets at depressed prices. While it is tempting to only buy during downturns, if your economic conditions worsen, you could end up having to sell those risky assets you bought at even lower prices. In other words:

Don’t play to win, play not to lose.

For the average investor, the purpose of having ample liquidity (i.e. riskless assets like short term bonds/cash) is to provide you with stability in case of job loss or another financial shock. You may experience prolonged financial distress, and liquidity is the only way to prevent you from raiding your 401(k) or other investment accounts. The last thing you want is to sell assets at a steep loss.

As for the right amount of liquidity to have, no one knows. Some say 6 months as an emergency fund, but I would shy on the side of more rather than less. When you are in the desert, having more water doesn’t hurt. Lastly, if you want to find out how the Long Term Capital Management story really ends, I highly recommend Lowenstein’s book. Thank you for reading!

If you liked this post, consider signing up for my newsletter.

This is post 25. Any code I have related to this post can be found here with the same numbering: https://github.com/nmaggiulli/of-dollars-and-data