I recently asked Twitter what personal finance topics they want me to write about and one of the most requested was:

How do I save (and invest) for a big purchase?

So whether you are saving up for a car, a home, a wedding, or some other big ticket item, what’s the best way to go about doing it?

I asked a few advisors at my firm and they all responded in the same way—cash, cash, cash. When it comes to saving for a big ticket item, cash is the safest way to get there. Period. Full stop.

But, I already know what you’re thinking:

What about inflation?

Yes, inflation is going to cost you 2-3% a year while you save. However, given that you are only saving for a short period of time (i.e. a few years), then the impact will be small.

For example, if you needed to save up $24,000 for a down payment on a house and you could afford to save $1,000 a month, it would take you 24 months (2 years) to get there without inflation. However, with 2% annual inflation, it’s going take you an extra month of saving $1,000 to reach your goal. That means that you would have to save $25,000 nominal dollars to get $24,000 of real purchasing power thanks to inflation.

Yes, this isn’t ideal, but it’s a small price to pay for the guarantee that you will have your money when you need it. In the grand scheme of things, the extra month isn’t a significant cost. This is why cash is the most sure-fire, lowest risk way to save for a big upcoming purchase.

But, what if you wanted to fight inflation while you were saving? Or what if you needed to save for a period longer than two years? Is cash still the best option?

To answer this question we will compare saving in cash to saving in bonds throughout history.

Does Saving in Bonds Beat Cash?

To test whether investing in bonds beats holding cash, we can run the same $1,000 a month saving exercise, but this time we will invest that money in U.S. Treasury bonds (via an ETF/index fund). By buying U.S. Treasury bonds we can earn some yield while also holding a low risk asset. What’s not to like?

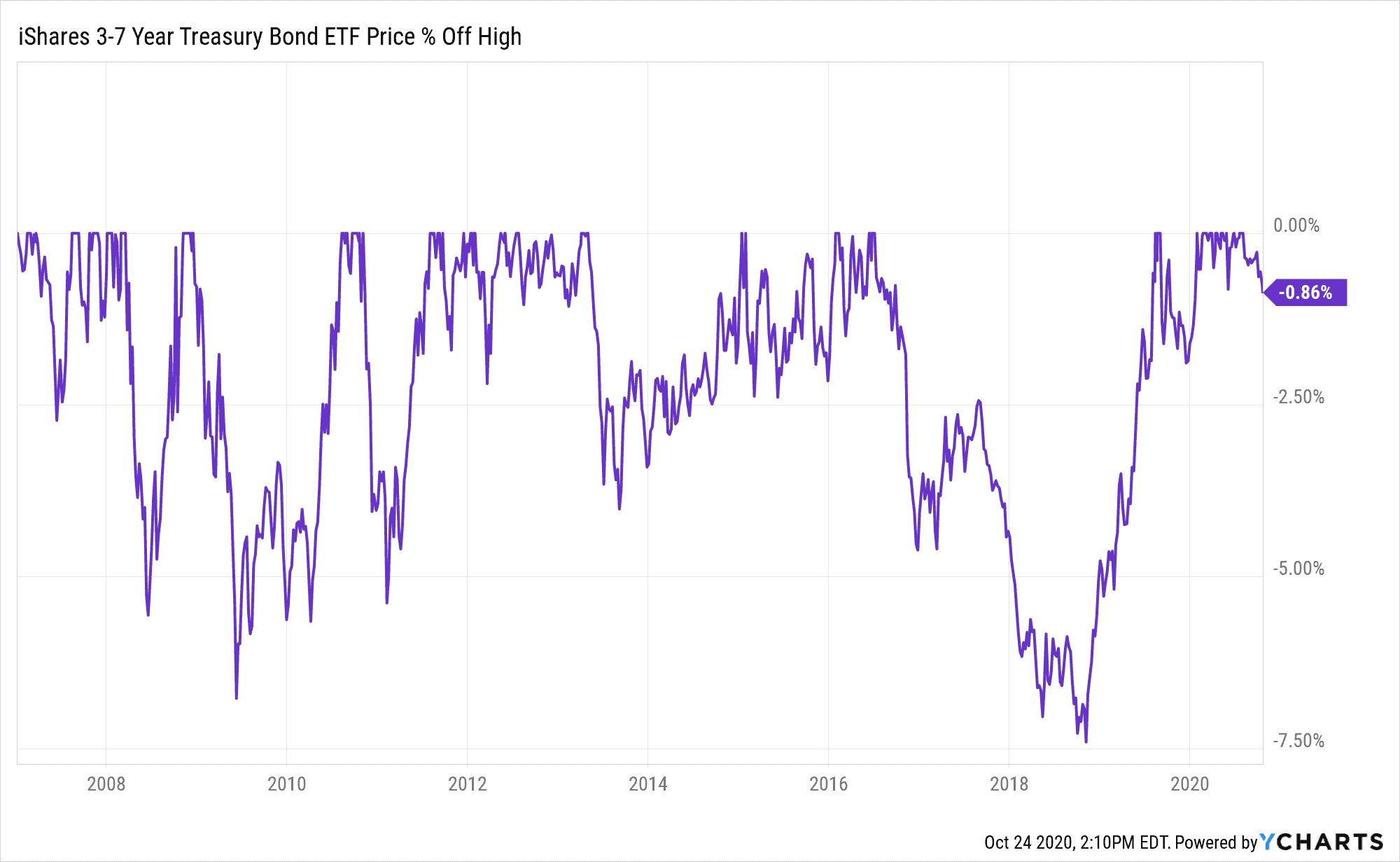

Well, low risk isn’t the same as no risk. As you can see below, intermediate U.S. Treasury bonds regularly lose 3% of their value (and sometimes more):

This illustrates how normal fluctuations in bond prices can push your savings goal further into the future.

Going back to our example of saving $1,000 a month until you reach $24,000, a 3% drop in bond prices near the finish line would reduce your portfolio value by nearly $750 (~3% of $24,000). This means that you would have to save an extra $1,000 (i.e. save for 1 additional month) to reach your $24,000 goal.

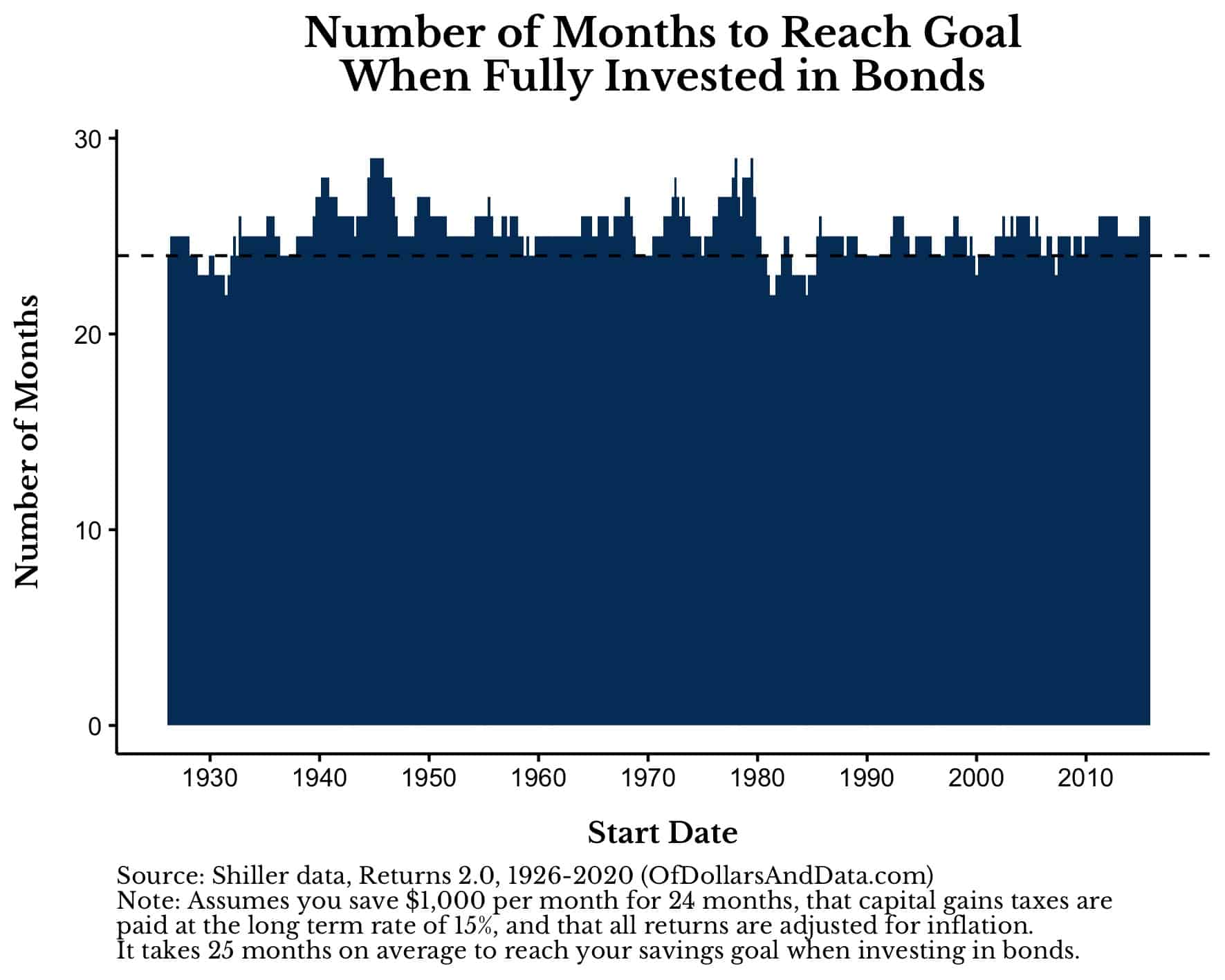

In fact, if we re-run this scenario across every period going back to 1926, this is exactly what we find. On average it takes 25 months to save $24,000 when investing $1,000 a month in U.S. Treasury bonds (after adjusting for inflation):

The dotted horizontal line in the chart above represents the amount of time it would take to reach our savings goal in a world with no inflation (i.e. 24 months). As you can see, most of the time we are above this cutoff, but sometimes we end up below when investing in bonds.

If we perform the same exercise while saving $1,000 a month in cash, we find that it actually takes about 26 months, on average, to reach our goal (after adjusting for inflation):

As you can see, bonds typically beat cash when saving for about two years, but not by much. Having to save for one extra month is a small inconvenience compared to worrying about whether bond prices might tumble when you need your money.

In fact, about 30% of the time since 1926 you would have been the same or better off holding cash versus investing in bonds to reach your $24,000 goal. This suggests that when saving for less than two years, cash is probably the optimal way to go since there is less risk around what might happen with your money. My colleagues’ intuition was accurate in this regard.

But what if you need to save for a big purchase that will take more than two years to reach? Should you change your strategy?

What If You Need to Save Beyond Two Years?

When saving beyond a two year time horizon, holding your money in cash can be much riskier than it initially seems.

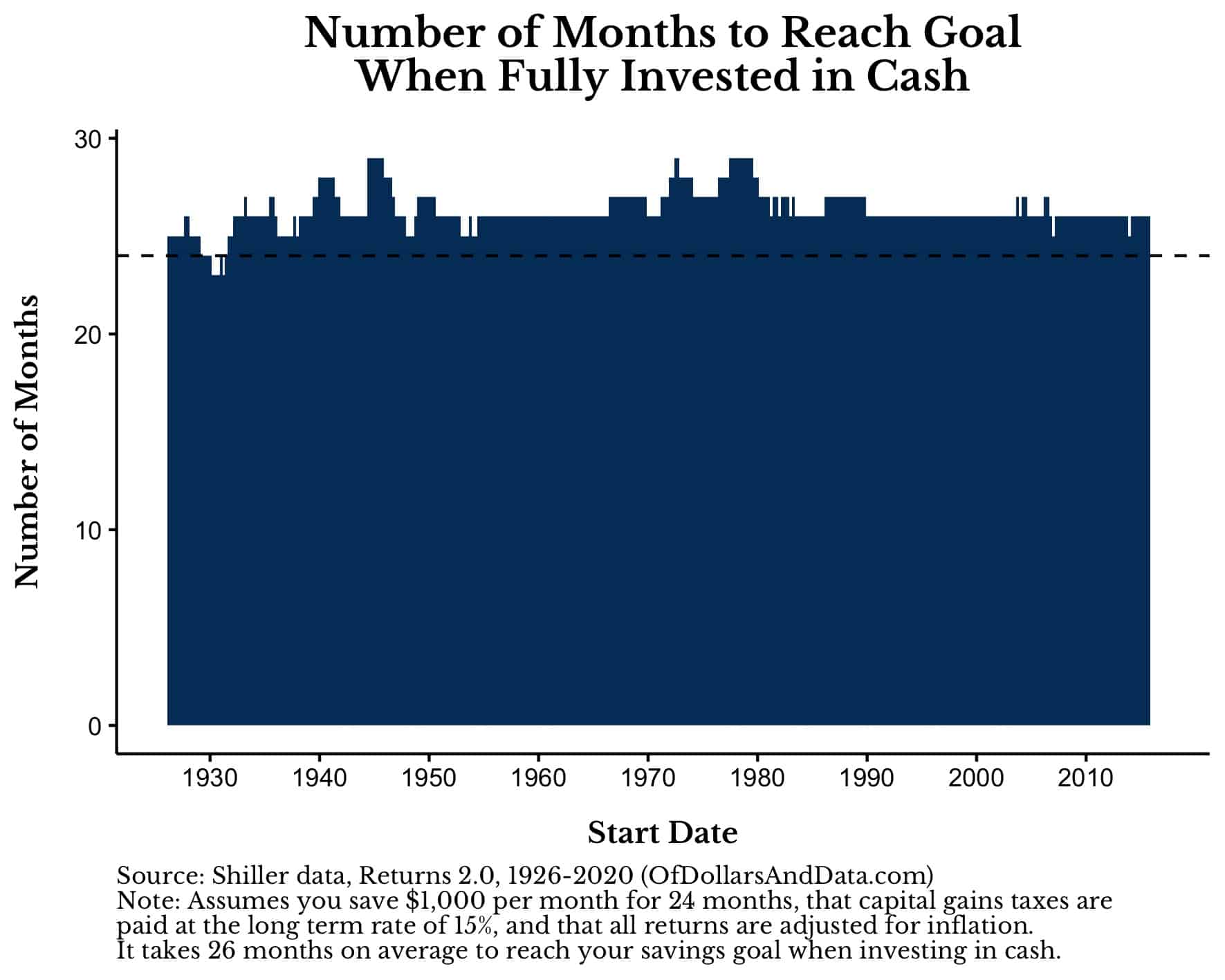

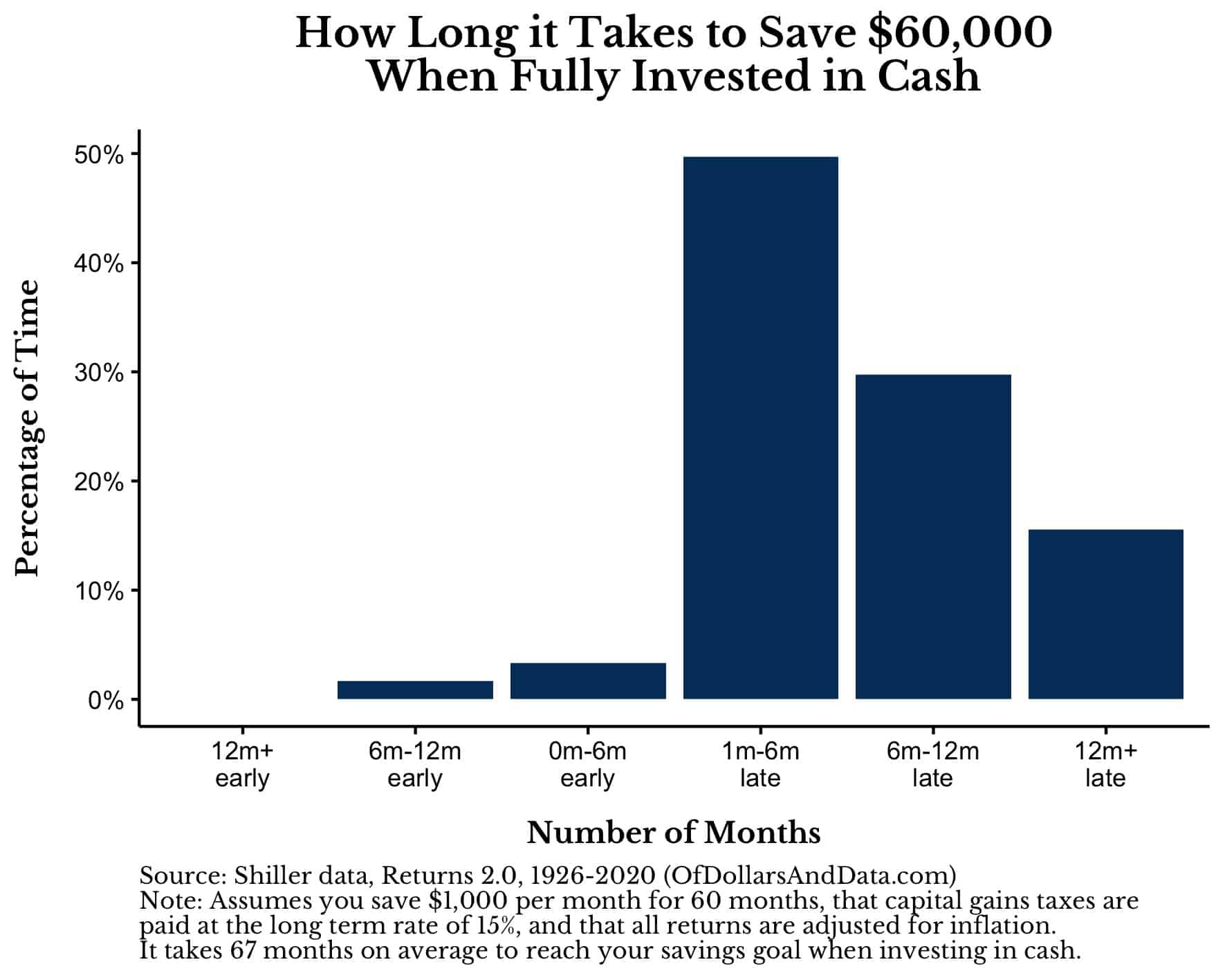

For example, if you wanted to save $60,000 by saving $1,000 a month in cash, we would expect it to take 60 months (i.e. 5 years) in a world with no inflation. However, when you actually perform this exercise going back to 1926, 50% of the time it would take you 61-66 months (i.e. 1m-6m late) to reach your goal and 15% of the time it would take you 72 months or more (i.e. 12m+ late):

On average, holding cash takes 67 months to reach the $60,000 goal. Why? Because the longer time horizon increases the impact of inflation on your purchasing power.

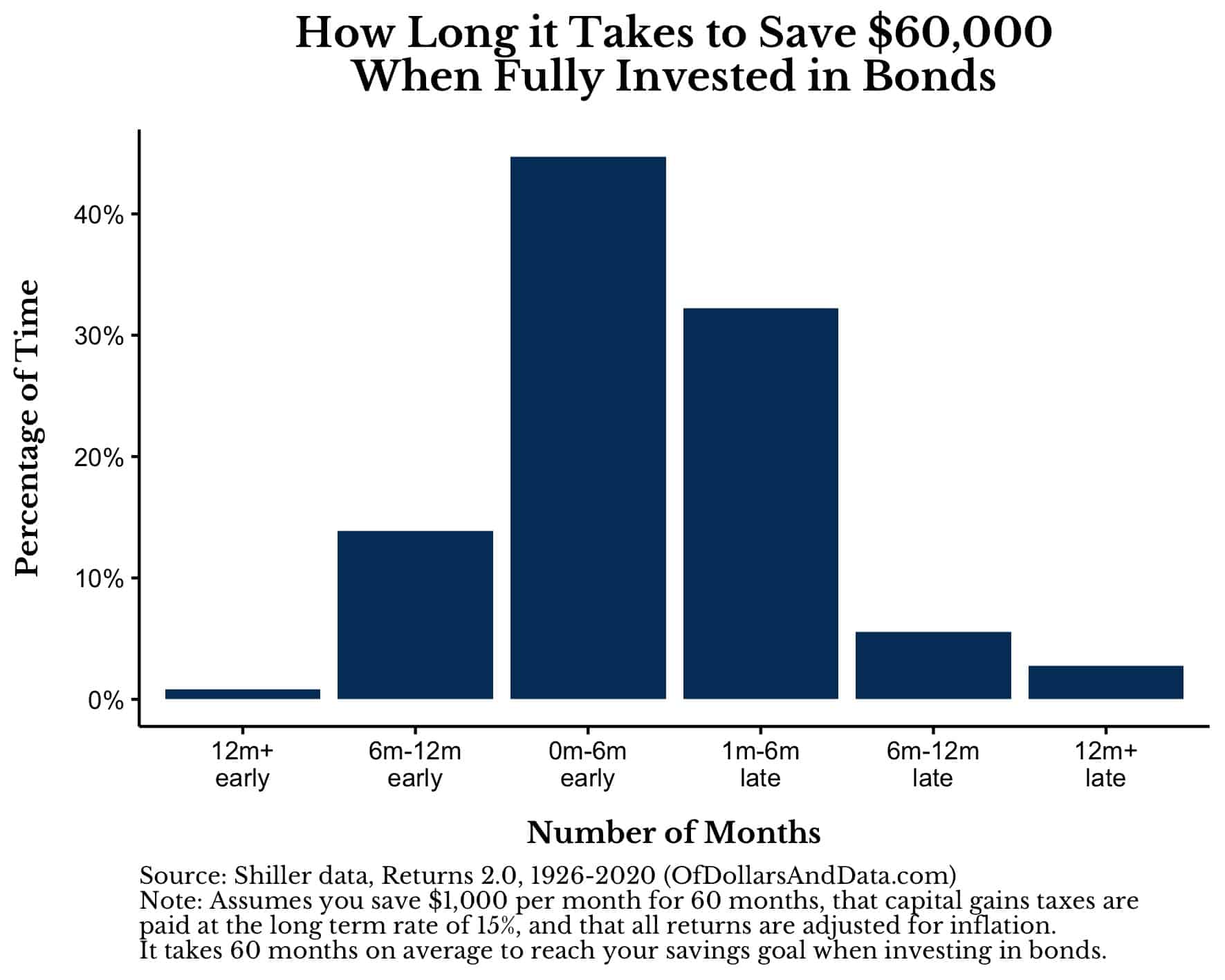

Compare this to investing in bonds where it only takes 60 months, on average, to reach your $60,000 goal:

Since bonds provide some yield, they can offset the impact of inflation to preserve your purchasing power.

More importantly, compared to when we were trying to save up $24,000 over 24 months, trying to save up $60,000 over 60 months is much riskier for cash. It’s no longer the case that one or two months of extra saving can offset the impact of inflation. Now it requires six months (or more) of additional cash savings to get there. Because of the longer time horizon, the risk of holding cash is now bigger than the risk of holding bonds.

You can see this more clearly by looking at how many additional months cash requires to reach the same savings goal as bonds based on different time horizons:

As you can see, regardless of when you start throughout history, cash typically underperforms bonds especially over longer time horizons.

Does this mean that there is an optimal point at which you should stop saving cash and start saving in bonds? Not exactly, but we can come up with a good guess.

For example, given that a two year savings time horizon slightly favors cash and a five year savings time horizon clearly favors bonds, the “switching point” will be somewhere in between. After reviewing the data, this point seems to be around the three year mark. So if you need to save for something that will take less than three years, use cash, otherwise, put your savings in bonds.

If you had done this throughout history, you would have reached your 36 month savings goal in about 37 months with bonds and 39 months with cash. This is a good rule of thumb that is backed by historical evidence and has worked through periods of high inflation, low inflation, and everything in between.

But, this begs the question: Can we do even better than bonds by investing our cash in stocks?

Does Saving in Stocks Beat Bonds?

For our last thought experiment we will do our same $1,000 a month exercise but invest it in the S&P 500 instead of U.S. Treasury bonds. How does this strategy fare against bonds? Well, most of the time it does better, but sometimes it does much, much worse.

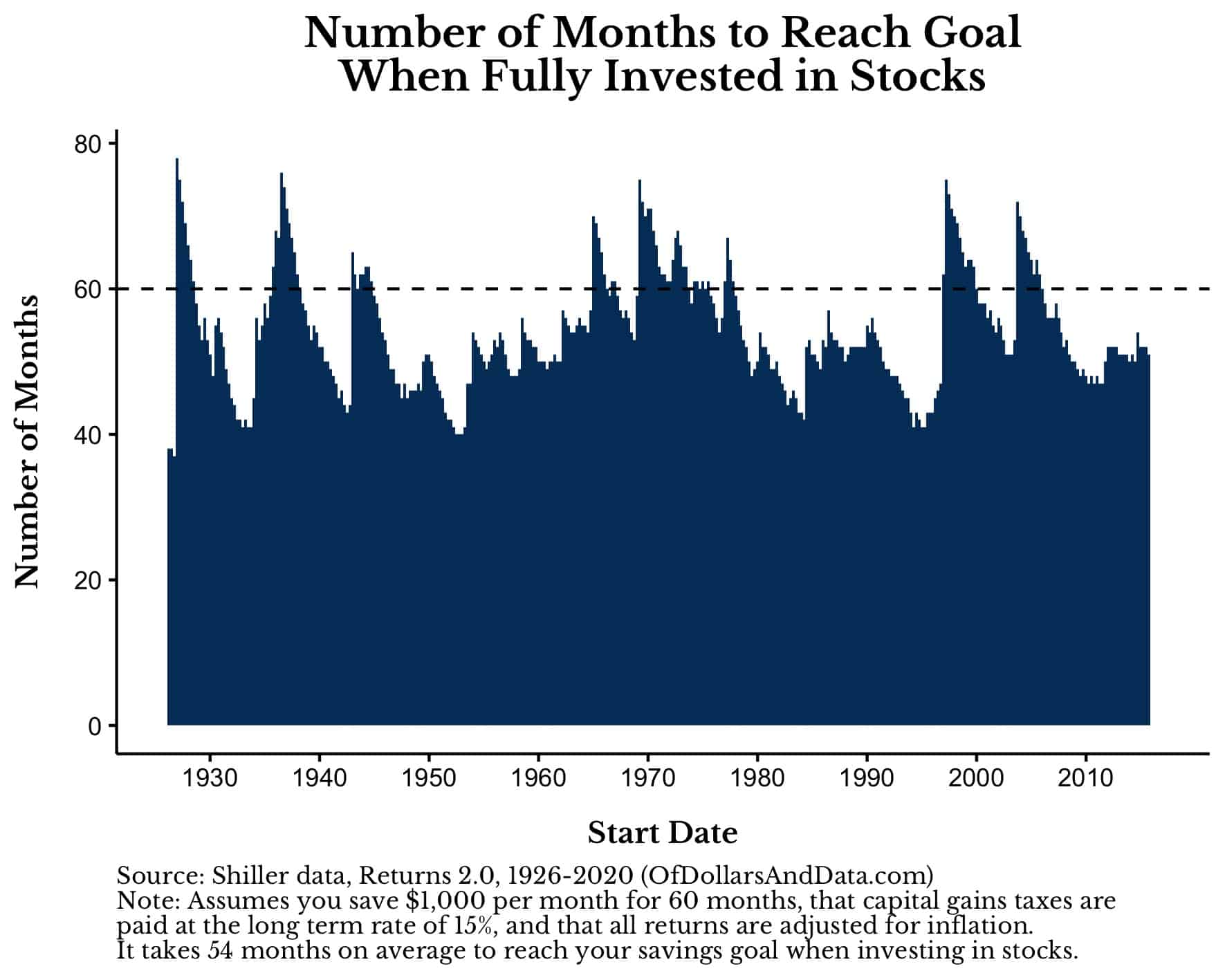

For example, if you saved $1,000 a month until you reached $60,000, it would typically take you 60 months if you invested that money in bonds, but only 54 months if you had invested that money in stocks:

However, sometimes it would have taken you far longer than 60 months to reach your goal.

We can see this more clearly by comparing the additional number of months it takes bonds to reach the same savings goal when compared to stocks for various time horizons across history:

As you can see, investing in stocks during major crashes (i.e. 1929, 1937, 1974, 2000, and 2008) would have taken you an additional year (or longer) to ultimately reach your savings goal when compared to investing in bonds.

More importantly, this analysis assumes you would have been able to continue to invest $1,000 every month regardless of economic conditions. In the real world though, we know that this won’t always be the case. This is the real risk of using stocks to save up for a larger purchase.

However, this decision is almost never going to be all-or-nothing. You don’t have to choose between a portfolio of 100% stocks or a portfolio of 100% bonds. In fact, when saving for a big purchase that is five years away (or more), you can choose a balanced portfolio that better fits your timeline and risk profile.

Bottom Line

Based on the evidence above, it’s clear that the length of time over which you have to save for a big purchase should help determine how you save for it. Over shorter periods, cash is king, but as a purchase goes further into the future, you have to consider other options. Unless you are willing to pay the inflation demon’s annual toll, this means reaching for yield/growth through fixed income, and, possibly, stocks.

Lastly, this analysis assumed that you would save a constant amount over time until you reach a goal. However, life rarely works out so well. If you happen to reach your goal earlier than anticipated, then you will need to invest that money in some way to preserve its purchasing power. Unfortunately, that either means foregoing cash in favor of higher yielding options, or saving more cash than you need in anticipation of inflation.

Either way, some areas of personal finance can be more art than science. I wish I could tell you the most optimal way to save for the future, but the world will never provide such certainty. As the world changes, the advice should change with it. With that being said, happy saving and thank you for reading!

If you liked this post, consider signing up for my newsletter.

This is post 213. Any code I have related to this post can be found here with the same numbering: https://github.com/nmaggiulli/of-dollars-and-data