This week I want to talk about the exciting world of investing. Not the boring, passive, safe way to the upper middle class that I recommend frequently, but the high conviction, high stakes kind of investing. This is for all of those people that pick stocks or think they can choose someone who picks stocks. This is all about the investment game.

And yes this is a game. There are winners and losers and 4 rules I recommend you follow to increase your chances of success. The rules I am going to discuss have nothing to do with how to pick stocks. Any advice I could give on picking a great stock would just regurgitate the ideas of others (i.e. Buffet says you should look for a good management, a wide economic moat, etc.) However, if I had to recommend one resource that summarizes the best historical stock picking strategies it would be What Has Worked in Investing by Tweedy, Brown LLC. With that being said, let’s dive into the rules:

1. Only Play Where Few Are Looking

I put this first because it is probably the most important. Many studies have shown that once a successful stock strategy has been publicized it almost immediately stops succeeding as a strategy. The reasoning is that as individuals learn about the strategy they rush into the market and bid away any future gains that could result from using it. The act of revealing the strategy makes it worthless. There are exceptions to this, but not many.

This same idea can be generalized to any area of the market where you have too much competition. While it is true that you can make money trading the AAPLs of the world, it is incredibly hard when everyone else is looking.

The earliest forms of value investing involved buying companies that had more net current assets (i.e. cash) than what they were selling for on the open market. This is like selling a wallet with $100 in it for $50 simply because you never opened it to see what was inside.

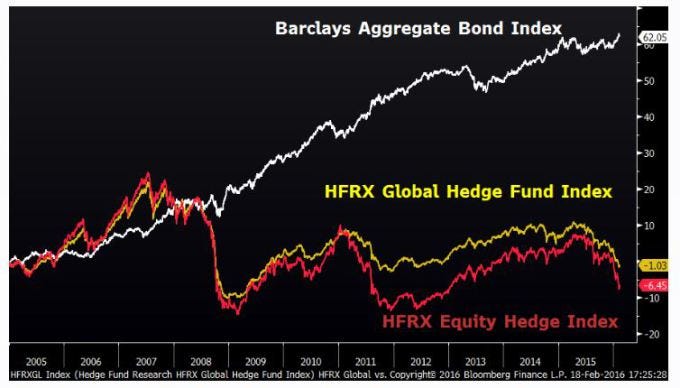

Recently Pension Partners wrote an in-depth piece about how equity hedge funds, on average, have seen their returns collapse in the last decade because there are too many hedge funds for the excess returns to go around:

The author compares the 10,000 hedge funds that exist to the 12,000 Starbucks that exist to illustrate how much competition there is in the industry. Equity hedge funds in particular are becoming more correlated with the S&P 500 (the correlation is close to 0.9 now). As a result, they are starting to perform much more like the market though they still charge high fees. This competition is eating away the excess returns.

If you want one convincing data point to “only play where few are looking”, consider Renaissance Technologies. Renaissance is a hedge fund whose flagship fund averaged ~72% annually from 1994–2014. They use extremely advanced statistical/mathematical models, keep this information under lock and key, and are (generally) not open to outside investors. The secrecy surrounding the firm and its methods embodies the “only play where few are looking” strategy.

2. Don’t Confuse Skill with Luck

It is very difficult to separate skill from luck, especially in the short run. Therefore, you cannot let a few wins clout your judgment about your true ability. Stay honest with yourself and remember that your track record will be affected by both skill and luck. Many great investors realize this relationship and admit that luck plays some role in their success.

There is a great story told by Nassim Taleb about the trader who received a low performance bonus and, in an attempt to get revenge, started trading his employer’s money wildly. Despite his best efforts to cost his employer dearly, he ended up making them lots of money before he was stopped. Some luck.

3. Only Play With What You Can Afford to Lose

There is a fascinating story about the investor Jesse L. Livermore who made the equivalent of $3 billion in one day during the great crash in 1929, but continued to make big bets afterwards until he lost it all. It illustrates the importance of having constraint with your active investment decisions. Whatever you invest you should be able to afford to lose. If you can’t afford to lose it, then build up ample emergency savings before you engage in active investment.

4. Remember That X% in Fees Should Deliver X%+ in Outperformance

If you are picking someone to pick stocks for you (i.e. a mutual fund, hedge fund, etc.) you should realize that they need to outperform their relevant benchmark (i.e. S&P 500) by more than their fee for you to be the same off as a passive fund. A 1% annual management fee means they should beat their benchmark by more than 1% annually. Rather than explain the math, which is not perfectly linear, just remember that an X% fee means you expect the fund to beat their benchmark by more than X%. This might seem obvious, but as the fee structures get more complex it gets more difficult to judge how much outperformance is needed.

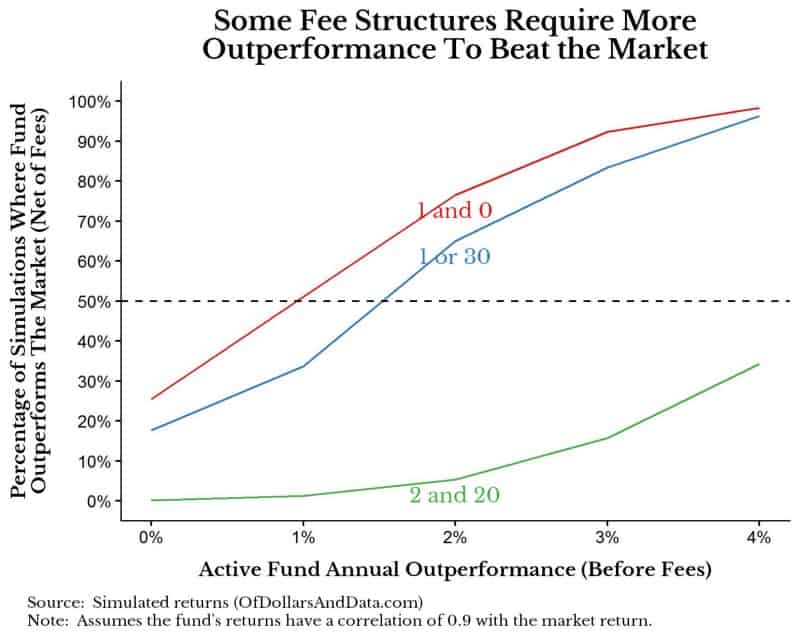

Fortunately, I ran a few hundred thousand different simulations of 40 year investment horizons comparing the performance of an active fund to a passive fund using different fee structures. I assume that the passive “market” fund gets a 10% annual return and 20% standard deviation while only charging 0.05% (5 bp) annually to its investors.

To do this I simulated correlated returns between the passive fund and an active fund while assuming the same level of risk, but varying the level of outperformance by the active fund. Before I show the results of the simulation, there are 3 fee structures I will present:

- 1 and 0: This structure charges a 1% management fee annually and a 0% performance fee.

- 1 or 30: This newer structure, based on comments from Gotham Asset Management, charges the higher of a 1% management fee or 30% performance fee above the benchmark. In addition, “the management fees charged in a year when the fund underperforms the benchmarks are deducted from the following year’s performance fee payment.”

- 2 and 20: This is the classic 2% management fee and 20% performance fee that hedge fund’s have used historically and I covered in my first post here. Currently hedge funds charge closer to 1% management and 17% performance.

Without further ado, let’s look at how these 3 fee structures stack up. The x-axis below represents the average amount of outperformance the active fund can obtain over its benchmark (annually) and the y-axis represents the percentage of total simulations where the fund beats the market benchmark. The dotted 50% line is the point where you would be the same off between the active and passive fund:

As you can see, with a “1 and 0” fee structure we need about 1% of outperformance to be the same as the passive market fund. However, the “2 and 20” fee structure requires over 4% of outperformance to get close to being the same off as a passive fund. The thing I like about this is it clearly illustrates how extractive “2 and 20” is and also offers much more promise for the newer “1 or 30” model.

If you vary the fund’s risk and correlation with the market, the results above will change, but the relative performance of the different fee structures will remain similar.

Should You Play the Investment Game?

While I do not recommend the active approach discussed above, I have a certain amount of respect for stock pickers, despite my articles to the contrary. Without active stock pickers we wouldn’t have functioning investment markets and all of the passive investors (myself included) wouldn’t get the free ride from their research.

If you like the thrill of active investing, but are unsure of your skills, you could try taking a small percentage of your total portfolio (i.e. less than 5%) to play the game. Even if you lose this few percent, you won’t be ruined, but remember, I am generally against this idea. Sometimes the best way to win is not to play. Thank you for reading!

If you liked this post, consider signing up for my newsletter.

This is post 13. Any code I have related to this post can be found here with the same numbering: https://github.com/nmaggiulli/of-dollars-and-data