Though the market is only 15% off its highs, as my colleague Michael Batnick recently wrote, “It feels a lot worse.” And it does. Bonds are having one of their worst years ever, stocks are down, and inflation is the highest it’s been in 40 years. With all this turmoil, you might be thinking that now is the right time to get out of the market.

Of course, you know I’m not a fan of market timing (see Ch. 14 in Just Keep Buying), but let’s say you’re right. Let’s say this is the beginning of the next 50%+ decline in U.S. stocks and you decide to get out now, nearly half a year since the most recent high. So, you move to cash, you watch the market crash, and then wait for the dust to settle before getting back in.

How long does it take for “the dust to settle”? Let’s say half a year to be sure. So six months after the bottom, you buy back into the S&P 500 at a lower price than where you sold. You’re officially a legend, a rockstar, an investing maverick. Congratulations!

But before you finish your victory lap, let me let you in on a little secret—you may have won the battle, but you will likely lose the war. I can explain.

Does Reasonable Market Timing Work?

I will refer to the market timing strategy described above, where someone calls the top/bottom within six months of the actual top/bottom, as the Reasonable Market Timing strategy. Why do I think it is reasonable? Because, unlike many other market timing strategies, this strategy assumes imperfect information as opposed to perfect information.

Perfect information is thinking you can sell the exact top or buy the exact bottom every time. This isn’t realistic. However, selling six months after the top and re-buying six months after the bottom? This seems reasonable. Someone just might be able to pull it off.

So, assuming it’s possible, does the Reasonable Market Timing strategy actually work?

Sometimes, yes, but, most of the time, no.

For example, let’s say you followed the Reasonable Market Timing strategy by selling six months after every top (where you knew a decline of at least 10% would occur in the future) and stayed in cash until six months after every bottom. If you used this strategy from January 2000 (near the peak of the DotCom bubble) until the end of 2009 (coming out of the Great Recession), you would’ve absolutely crushed Buy & Hold.

The chart below illustrates this by showing Buy & Hold (in black) versus the Reasonable Market Timing strategy (in blue) for the S&P 500 from 2000-2009. Note that the local market tops are denoted by green dots and the local market bottoms are denoted by red dots on the Buy & Hold line.

As you can see, the Reasonable Market Timing strategy moves to cash six months after the top and buys back in six months after each bottom, to glorious effect. In the long run, it easily beats Buy & Hold because it avoids two 50% declines in the market.

But what if there aren’t any big declines? What happens then? The strategy no longer looks so hot.

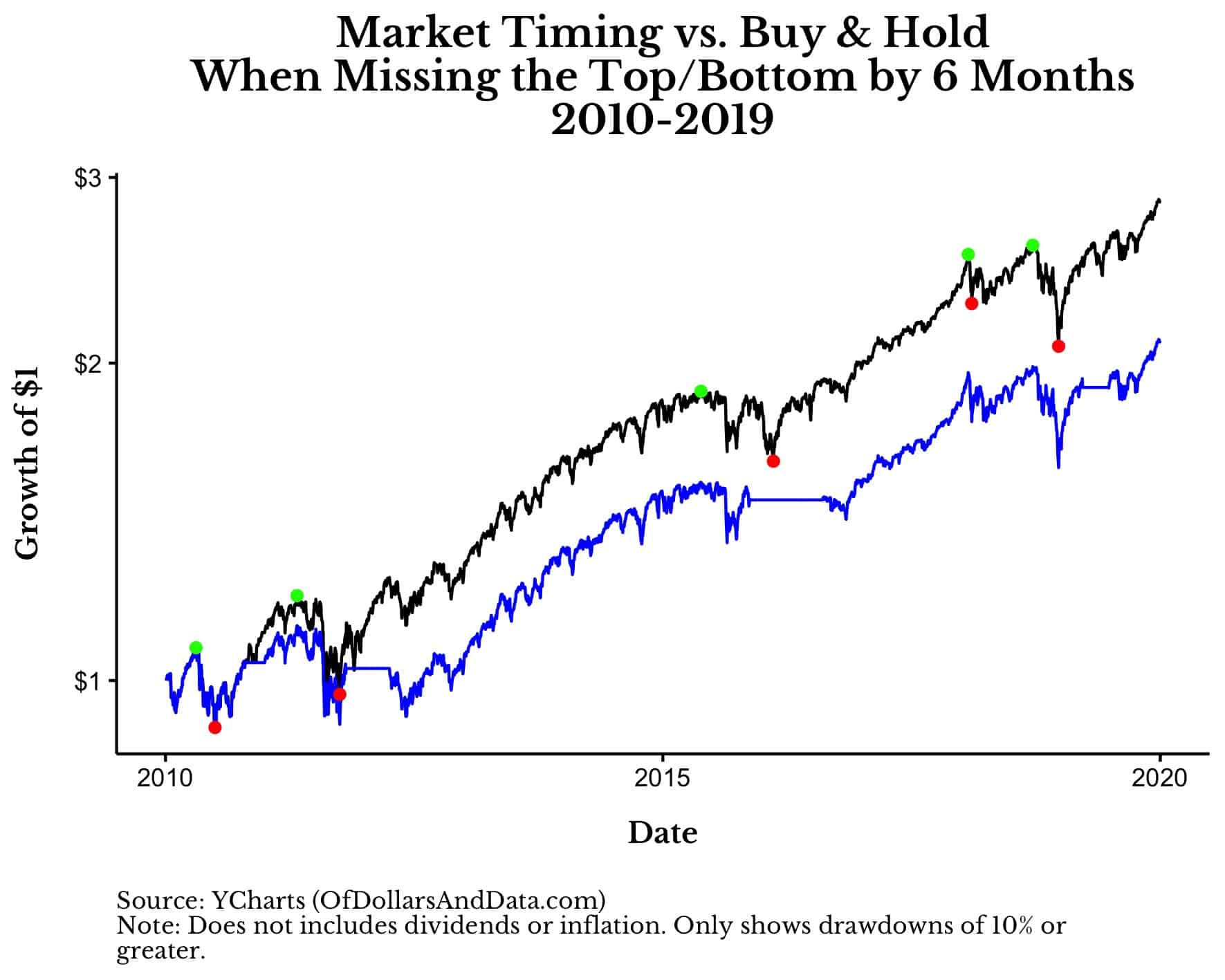

For example, if you followed the Reasonable Market Timing strategy from January 2010 to 2020, you would’ve underperformed Buy & Hold by a significant margin:

In this case the Reasonable Market Timing strategy gets humiliated by Buy & Hold because it has too many false positives. It exits the market expecting a big decline, but that big decline never occurs. As a result, it ends up re-investing at a higher average price.

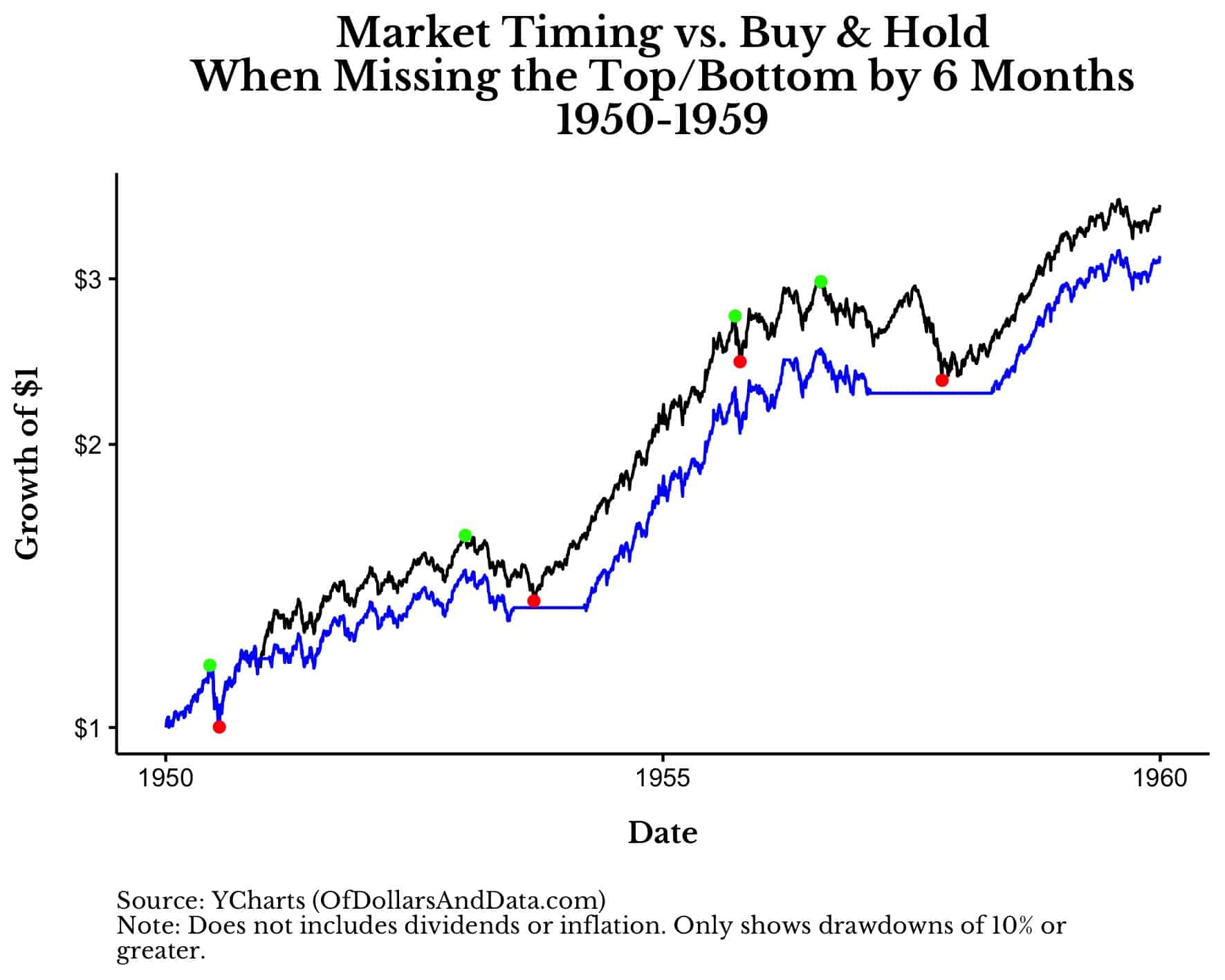

Unfortunately for the Reasonable Market Timing strategy, this is usually what happens. For example, consider the strategy from 1950-1959:

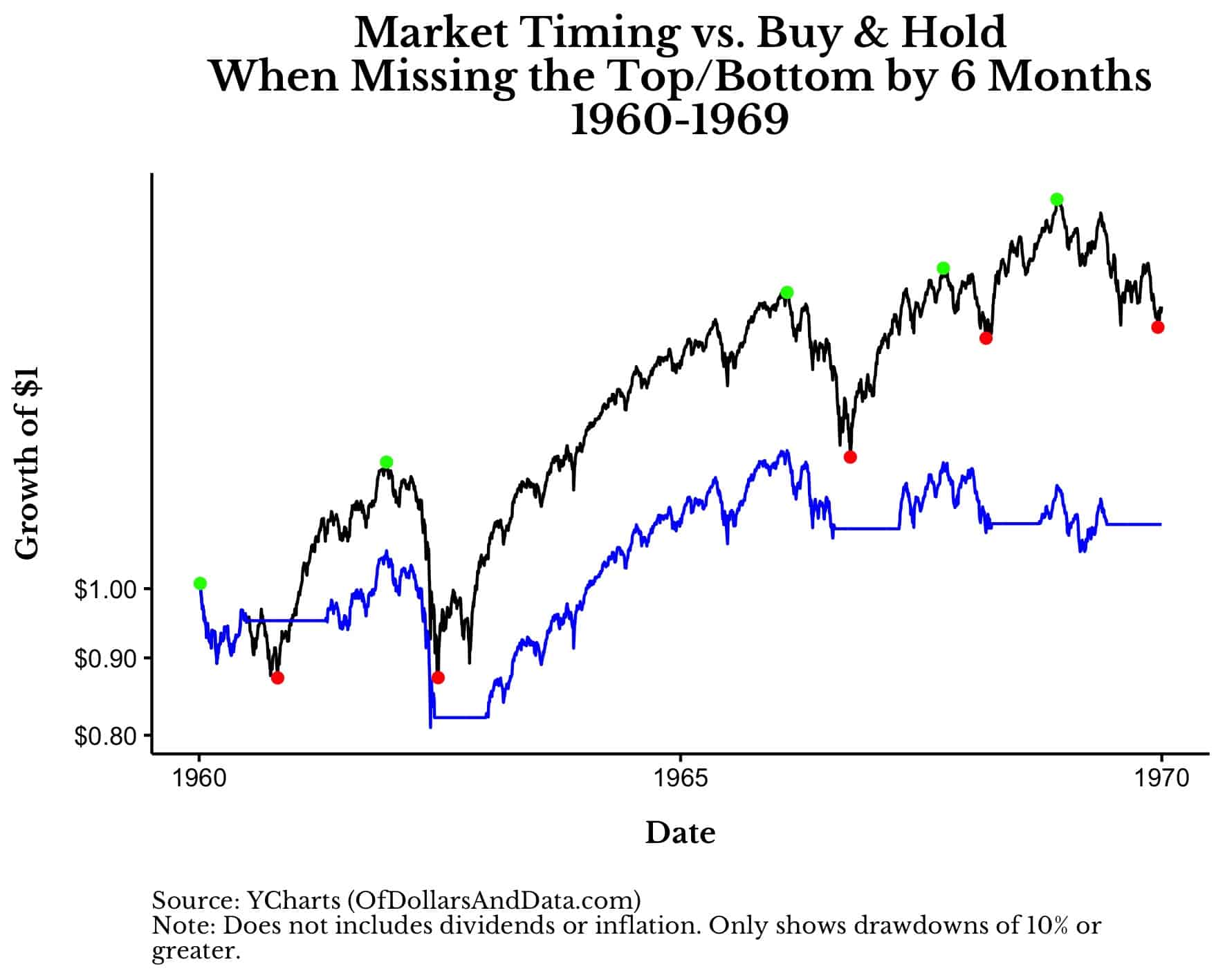

Or from 1960-1969:

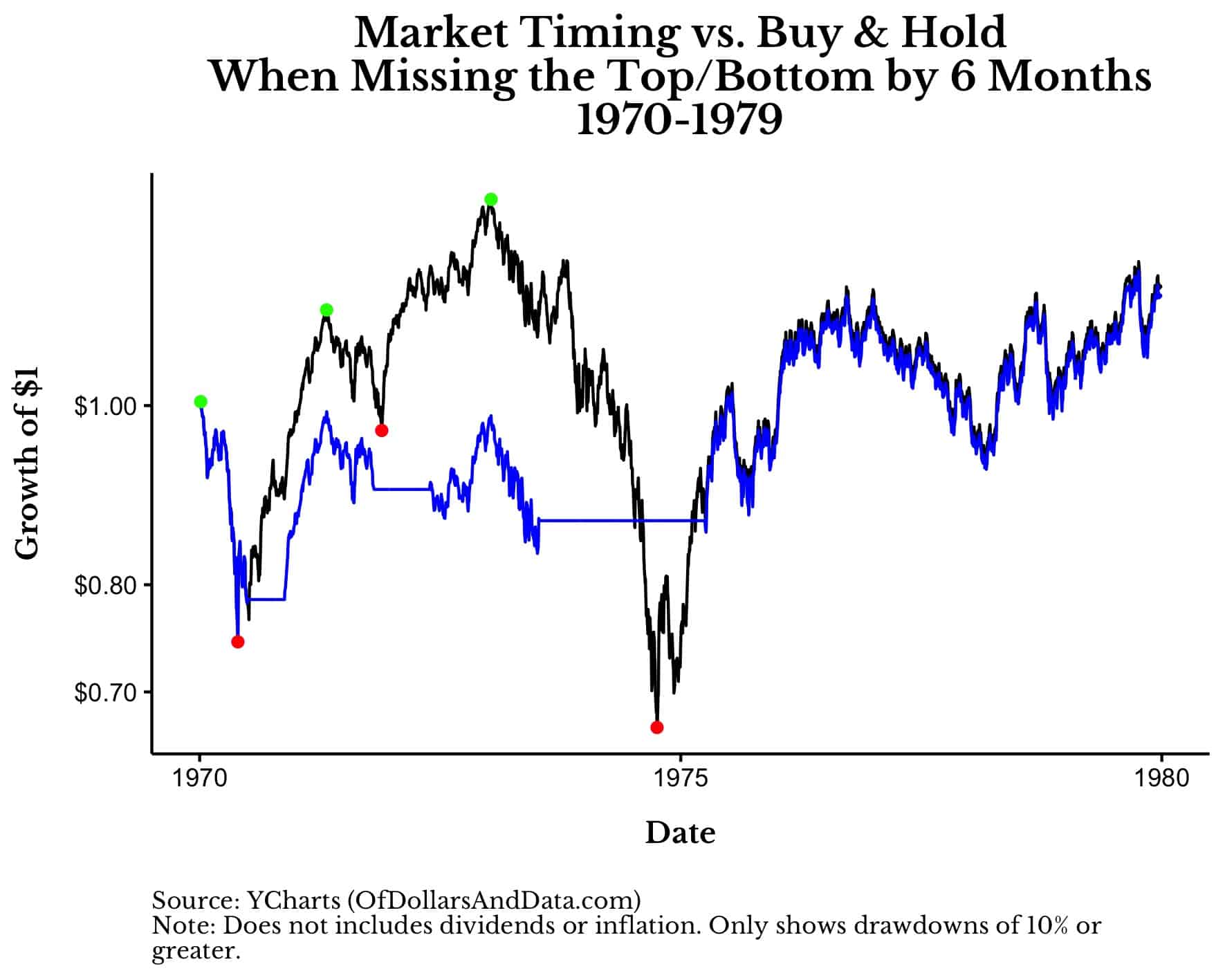

Or from 1970-1979:

In all of these cases, the Reasonable Market Timing strategy either underperformed or barely kept pace with Buy & Hold. The reasoning is simple—big declines in the S&P 500 have been rare throughout history. Because of this, it is difficult to identify (and avoid) these declines beforehand. As a result, this strategy ends up exiting the market too often.

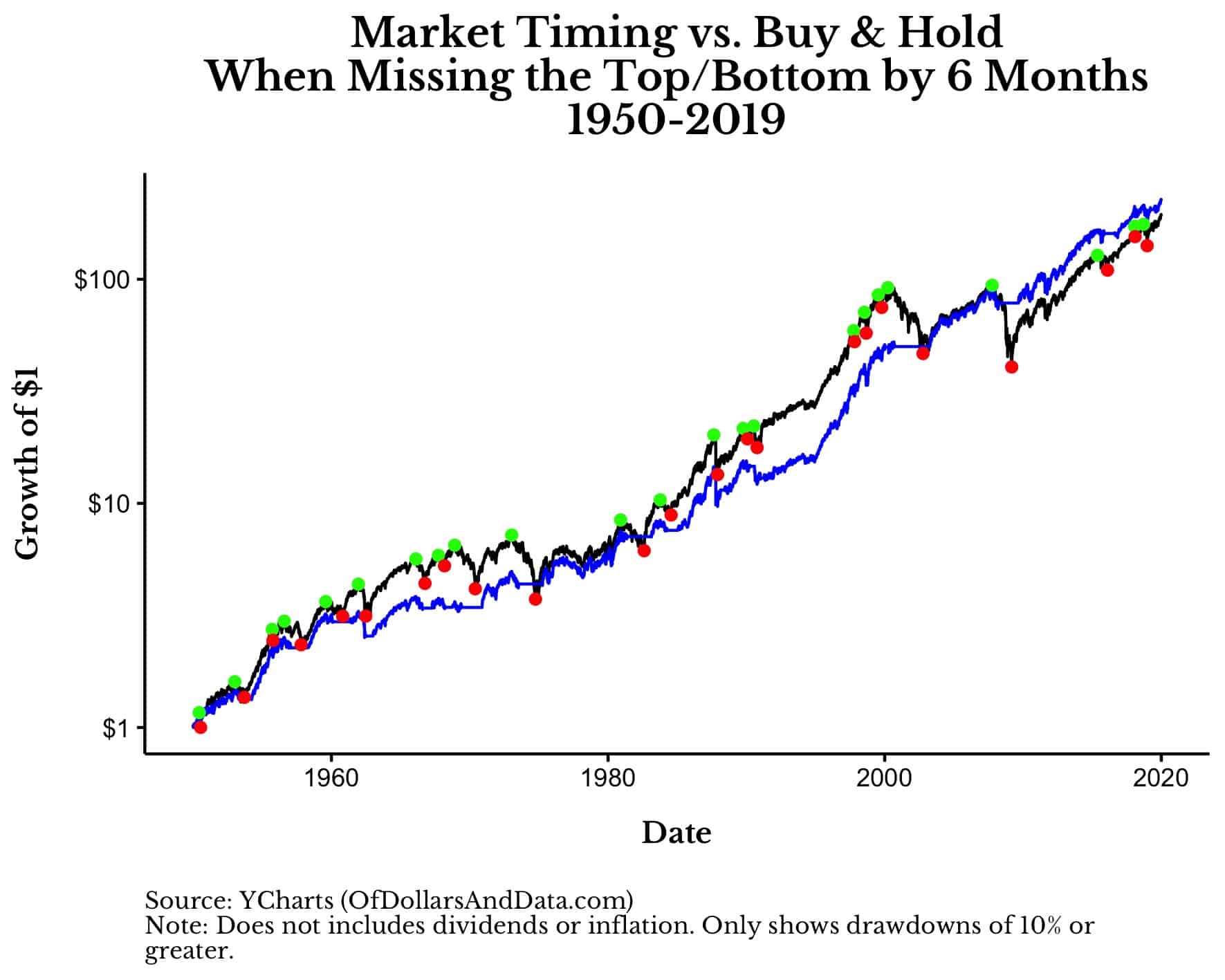

But, does the strategy make up for all the times it is wrong when it occasionally gets it right? Using data from 1950-2019, the answer is technically yes:

However, there’s a big problem here. For the first 59 years (from 1950-2009) the strategy underperforms Buy & Hold for almost the entire time! So who in their right mind could’ve followed such a strategy? No one. No rational investor could stick with this while underperforming for so long. This is why even a reasonable market timing strategy can be so difficult to execute in practice.

More importantly, this strategy assumes you follow the rules consistently over decades. But so many market timers do no such thing. They jump in and out based upon gut feel, not a rules-based approach which has a chance of outperforming. As a result, even the Reasonable Market Timing strategy isn’t reasonable when you take into account human nature.

So, if you do successfully time the market, you should take your victory lap and move on. Never do it again. Just quit while you’re ahead. Why? Because what you’ve done is like hitting the lotto. You’ve made money in a game (i.e. market timing) where you usually lose money.

Smile and forget that it ever happened. Because if you don’t, I can almost guarantee that you’ll regret it. When? I don’t know. Maybe not in this crash or the next one. But maybe in the one after that, or the one after that, or the one after that.

There will come a time when your gut is wrong and you exit the market when you shouldn’t have. You only need to consider the crash (and recovery) of March 2020 for an example of this.

Of course, maybe this time is different. Maybe the Fed is the arbiter of the market. Maybe passive investing has gotten too big. Maybe human nature has permanently changed.

But, I beg to differ. Because I’m not here to win the battle, I’m here to win the war. So market timers, permabears, and whoever else that thinks this is the end, wave your flags high. Wave them high for all to see. You may be right now, but you’ll be wrong later.

For everyone else, Just Keep Buying and thank you for reading!

If you liked this post, consider signing up for my newsletter.

This is post 294. Any code I have related to this post can be found here with the same numbering: https://github.com/nmaggiulli/of-dollars-and-data