So you’ve decided that you want to invest your money into U.S. Treasury bonds, but you’re not sure which ones to get. Should you buy short-term, intermediate-term, or long-term Treasury bonds?

Well, you’ve come to the right place. This post will explain the pros and cons of investing in U.S. Treasury bonds of different maturities (i.e. short, intermediate, and long-term) so you can find the right fit for your portfolio.

But, before we dig in, let’s review what short, intermediate, and long-term bonds actually are.

What are Short, Intermediate, and Long-Term Bonds?

As a quick reminder:

- Short-term bonds: Mature in less than 2 years.

- Intermediate-term bonds: Mature in 2 to 10 years.

- Long-term bonds: Mature in over 10 years.

In particular, the U.S. Treasury has different names for short-term, intermediate-term, and long-term bonds:

- Bills: These are short-term Treasury securities with maturities of one year or less. For example, you might buy 1-month Treasury bills, 6-month Treasury bills, or 1-Year Treasury bills. They are also commonly known as “T-bills”.

- Notes: These are intermediate term Treasury securities with maturities of 2 to 10 years. The most commonly referenced intermediate-term Treasury security is the 10-Year Treasury note.

- Bonds: These are long-term Treasury securities with a maturity of over 10 years. The most popular among these are the 20-Year and 30-Year Treasury bond.

For the purposes of this article, I will compare 1-month Treasury bills (short-term), 5-Year Treasury notes (intermediate-term), and 20-Year Treasury bonds (long-term) in the sections that follow. You can buy these bonds:

- Directly through TreasuryDirect,

- Directly through your brokerage account, or

- Indirectly through an index fund/ETF (if you want to diversify your bond holdings).

Now that we have a general idea of what short, intermediate, and long-term bonds are and how the U.S. Treasury refers to them, let’s explore how their performance differs.

How Do Bills, Notes, and Bonds Perform?

Outside of the difference in maturity, bills, notes, and bonds also differ in their level of risk and return that they provide to investors. In general, Treasury bills tend to have less risk than Treasury notes which tend to have less risk than Treasury bonds. So in terms of risk it goes:

Risk

Treasury bills < Treasury notes < Treasury bonds

The same pattern holds for returns. Treasury bills tend to have lower returns than Treasury notes which have lower returns than Treasury bonds:

Returns

Treasury bills < Treasury notes < Treasury bonds

Why is this true? Because, generally, its riskier to lock up your capital over a longer period of time. Therefore, investors will demand higher yields (i.e. higher returns) to do so. Let’s demonstrate how this plays out in the real world with an example.

Let’s say on January 3, 2022 you bought a 5-Year Treasury note and I bought 1-Year Treasury bill. At the time, 5-Year Treasuries were paying 1.37% and 1-Year T-bills were paying 0.42%. Unfortunately for both of us, interest rates increased dramatically throughout 2022 to the point where 5-year Treasury Notes were paying 3.94% and 1-Year T-bills were paying 4.72% on January 3, 2023 (one year later).

This isn’t great for either of us, who bought when rates were much lower and saw our bonds decline in price as rates increased throughout 2022. However, this situation is far worse for you, the owner of the 5-Year Treasury note. Why? Because you still have your capital locked up in a Treasury note paying 1.37% for the next four years though current rates are much higher. While my T-bill took a hit during 2022, at least now (in 2023) I can re-invest my capital at higher rates. You can’t unless you sell your Treasury note for a loss.

This is why maturity is the biggest determinant of a Treasury security’s risk and return. We can see this clearly in the data if we look at the average 1-year inflation-adjusted return and standard deviation of 1-month Treasury bills, 5-Year Treasury notes, and 20-Year Treasury bonds from 1926-2022:

| Duration | Avg. 1-Year Return | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| 1-Month Treasury Bills | 0.35% | 3.84% |

| 5-Year Treasury Notes | 2.14% | 6.67% |

| 20-Year Treasury Bonds | 2.8% | 10.43% |

As predicted, as maturity increases so does risk and real return. However, these aggregate statistics hide a lot of what is happening with these bonds over time. If we were to look at the total real return by decade for these maturities, we would get a much better idea of their performance:

As you can see, there isn’t a consistent pattern in the returns of these various Treasury securities over time. Though 20-Year Treasury bonds tend to outperform notes and bills, there are clear exceptions to this rule.

More importantly, most of the return generated by Treasury bonds above notes and bills occurred within the last four decades. If we were to recreate the same table from above while excluding all the data since 1980, we would discover that Treasury bonds don’t always outperform Treasury notes:

| Duration | Avg. 1-Year Return | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| 1-Month Treasury Bills | -0.01% | 4.49% |

| 5-Year Treasury Notes | 1.11% | 5.93% |

| 20-Year Treasury Bonds | 0.74% | 7.55% |

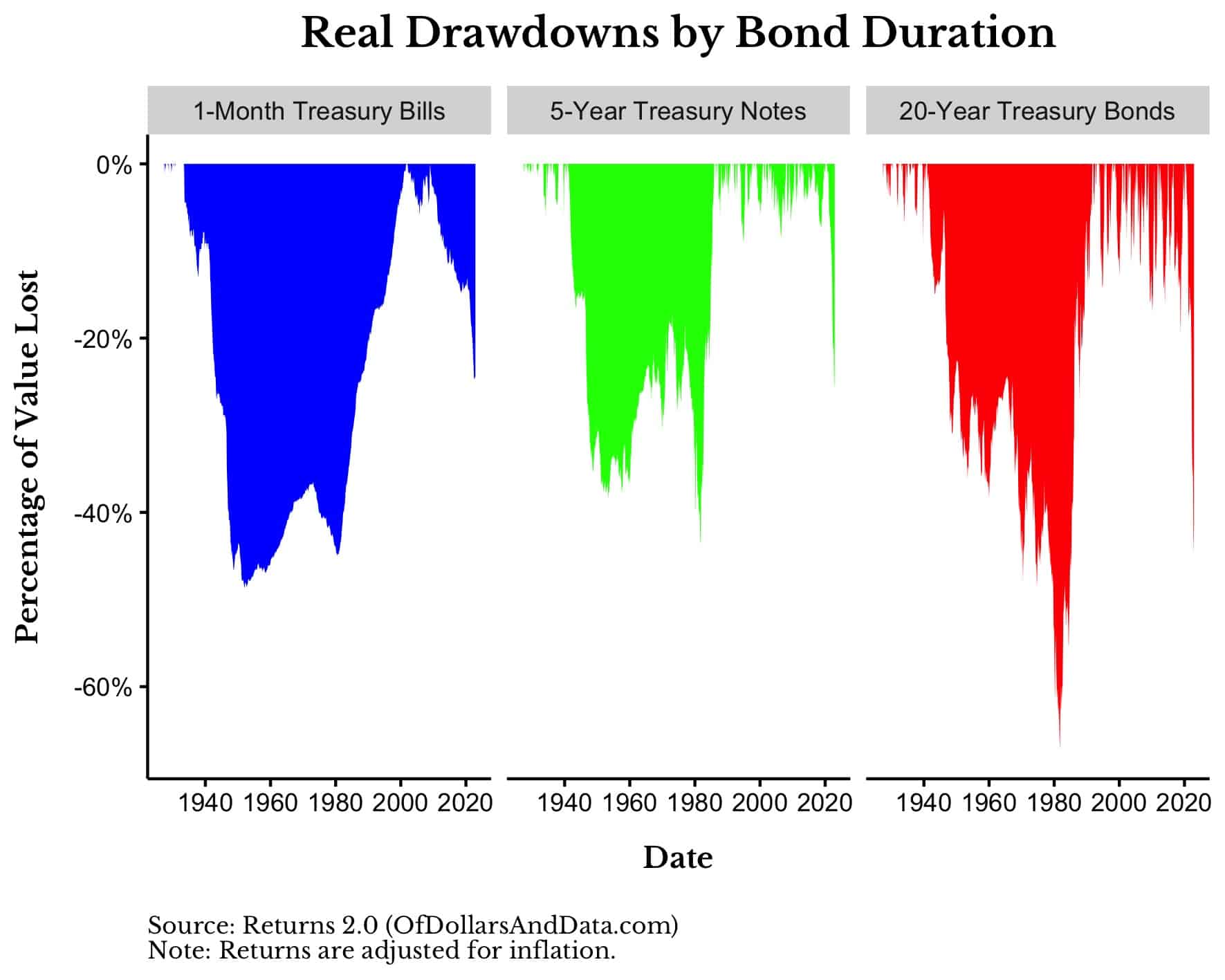

As you can see, before 1980 5-Year Treasury notes outperformed 20-Year Treasury bonds while also experiencing far less risk! We can see this more clearly if we examine the total drawdowns in these various bond maturities since 1926. As a reminder, a drawdown shows the total percentage decline from an all-time high:

Unfortunately, this plot highlights how the definition of risk isn’t the same in every time horizon. While 1-month Treasury bills are less likely to fluctuate than 5-Year Treasury notes, they also have experienced more severe drawdowns over longer periods of time. This suggests that longer bond maturities don’t always correspond with higher returns and higher risks as theory would predict. As the noted economist and MIT professor Fischer Black once stated:

Markets look a lot less efficient from the banks of the Hudson than from the banks of the Charles.

Now that we have looked at the performance of bonds of various maturities, let’s wrap things up by summarizing what we’ve learned and how you can use this information to pick the right bond for you.

How to Find the Right Bonds For You

Given the historical data above, it might seem like intermediate bonds (Treasury notes) are the optimal bond choice for most investors. While Treasury notes have had a higher historical return per unit risk than any other Treasury security, I don’t think we can crown them as the clear winner. Why?

Because every investor is looking for different things. If you want stable returns and a predictable stream of income, Treasury bills might be better than Treasury notes or Treasury bonds. However, if you are willing to take on more risk in exchange for higher potential returns, then Treasury bills probably aren’t the right choice.

Personally, I have only ever purchased intermediate-term Treasury notes and short-term Treasury bills. I am generally against owning long-term Treasury bonds because (as demonstrated above) the risks aren’t worth the rewards most of the time. However, I could imagine a scenario where buying long-term Treasury bonds would make sense. For example, back in September 1981 a 20-Year Treasury bond was yielding 15.78%. It would be hard for me to say “No” to 15.78% for 20 years.

This example demonstrates how investing is more of an art than a science. What works in one period may not work in another. What works for one person may fail for someone else. There are few hard truths in investing, but there are many general guidelines. This is as true with Treasury bonds as with anything else.

So, figure out what you want out of life, then choose the Treasury bonds that will help you get there. That could mean short-term bonds. That could mean intermediate or long-term bonds. That could mean all of the above.

It could even mean picking the bonds with the highest current yield. Though long-term Treasury bonds tend to have the highest yields, this isn’t always the case. For example, as of today the Treasury securities with highest yields are 6-month Treasury bills. Maybe you should buy those, then wait and see what happens to rates before deciding what to do next.

Ultimately, what matters is figuring out what works for you. That’s how you find the right bonds.

Happy investing and thank you for reading!

If you liked this post, consider signing up for my newsletter.

This is post 333. Any code I have related to this post can be found here with the same numbering: https://github.com/nmaggiulli/of-dollars-and-data