In his first year he turned $15,000 into $193 million. The following year he took $3 million and made it into $177 million. You might be thinking that I am talking about one of the greatest investors of all time, but I’m not. The person behind these outsized returns is Jason Blum, a film producer and the CEO of Blumhouse Productions. You may not have heard of Blumhouse, but their films have some of the highest return on investment in all of Hollywood.

Those first two films, Paranormal Activity and Paranormal Activity 2, opened Jason Blum’s eyes to a new way of making consistent money in the film industry. Blum’s discovery was to make microbudget horror films (typically less than $5 million per film) by following a set of strict rules. In other words, stay on script.

For Blumhouse these rules include:

- Not too many speaking parts. If an extra ever speaks in a film you have to pay them an additional $400 by law. Preventing extras from speaking reduces costs and arguably makes their movies scarier.

- Not too many locations. Ideally, the whole movie happens at one location (i.e. a house, the woods, a school, etc.) to reduce costs.

- Pay your talent as little as possible, but give them upside if the movie succeeds. Therefore, your big name actors/actresses get far more equity than normal, but get basically nothing if the film flops.

- Never, ever break your budget. This is the iron law of Blumhouse.

A perfect example of their process in action is the film The Boy Next Door, which got 10% on Rotten Tomatoes and a 33% audience score. Despite these bad reviews, the film grossed $52.4 million on a $4 million budget! An arguably terrible film made 10x because Blumhouse sticks to its plan.

This idea is relevant for you as an investor because there is plenty of evidence that the typical investor would be better suited if they stuck to their investment plan. Joel Greenblatt reminds us that investors that manage their own portfolios will underperform portfolios managed by a predetermined set of rules despite the fact that the “self-managed” investors are choosing from the same set of top ranked stocks as the rules based investors. I found this idea by reading The Acquirer’s Multiple by Tobias Carlisle, who discusses how investors feel about rules:

Many investors hate strict rules. They think it’s better to use output from the simple rule and then decide whether to follow it. This isn’t a bad way to go. Experts make better decisions when they use simple rules. But they don’t do as well as the simple rule alone.

It seems hard to believe that a simple rule (i.e. “buy cheap stocks”) can outperform the complex processing power of the human mind, but the evidence suggests that this is true in investing. Though we think we can outsmart such simplistic investment notions, chances are we cannot.

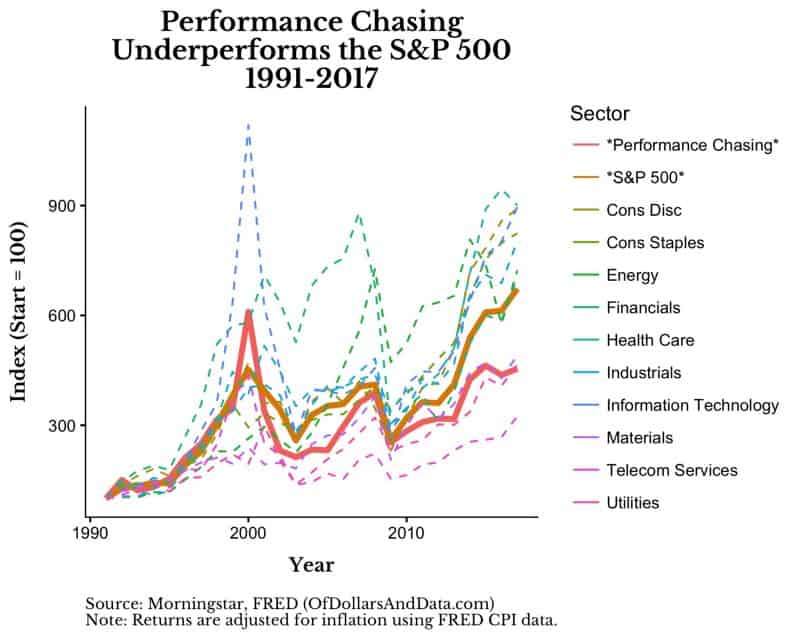

To further illustrate this idea, I got some S&P 500 sector performance data from Lawrence Hamtil (follow him on Twitter) and wanted to test whether sticking to one sector would be preferable to a performance chasing type strategy. In the performance chasing strategy, you would find the best returning sector in the prior calendar year and invest in that sector in the current calendar year. For example, if “Healthcare” stocks did the best in 1990, you would put all of your money into them for 1991. If “Energy” stocks did the best in 1991, you would sell your “Healthcare” stocks and put all of your money into “Energy” stocks for 1992. And so forth.

After plotting the respective performance of each sector against the performance chasing strategy, you can see that the performance chasing strategy performs quite poorly. The strategy only beats two individual sectors from 1991–2017 and it does so with the second highest amount of risk (standard deviation) among all sectors. Note that the performance chasing strategy and the S&P 500 overall are plotted with larger solid lines to differentiate among the 10 dotted sector performance lines:

As you can see, sticking to even one particular sector, though not ideal, would almost always have beaten out a strategy that constantly jumps around. And this is true before we take into account taxes and transaction costs, which make performance chasing even more undesirable. Of course, this was just one strategy tested over a short period of time among a large number of other possible strategies, but it is another example of how investors can underperform as a result of performance chasing and not sticking to an investment plan.

Lastly, I do not want to imply that all strategies are created equal. If you stick to a bad investment plan, you will do poorly. However, if you can find a strategy with good historical long term performance across different markets, sticking it to it can work wonders.

What About Having Fun?

The great economist John Maynard Keynes once said:

Investment is intolerably boring and overexacting to anyone who is entirely exempt from the gambling instinct; whilst he who has it must pay to this propensity the appropriate toll.

I couldn’t agree more. The problem with sticking to most investment plans is that they are quite boring. There is no thrill in buy and holding 500+ stocks and waiting to retire. If you find this is a problem for you, I suggest taking a small percentage of your portfolio (~5%) and just betting it on the things you believe in. This will allow you to feed your “gambling instinct” without any worry of breaking the bank and ruining your future financial security.

Lastly, if you are interested in learning more about Blumhouse Productions (i.e. the value investors of Hollywood) check out this Planet Money podcast episode that tipped me off to their genius methods. As always, thank you for reading!

If you liked this post, consider signing up for my newsletter.

This is post 63. Any code I have related to this post can be found here with the same numbering: https://github.com/nmaggiulli/of-dollars-and-data