One of the most common questions I get asked when it comes to which kinds of stock ETFs/mutual funds to invest in is:

What do you think about dividend paying ETFs?

After all, if dividends are just profits paid from a company to its shareholders, then those companies that pay more in dividends should be better than those that pay less (or none at all), right?

Unfortunately, it’s not that simple. While it might seem straightforward to assume that companies paying higher dividends are better investments, this view overlooks some key changes in corporate strategy and market composition that have occurred in recent decades. Due to such changes, investing in dividend paying stocks may never be the same.

But before we dive into these issues, let’s take a look at how dividend paying stocks have performed historically.

How Have Dividend Paying Stocks Performed Historically?

When it comes to investing in dividend paying stocks, the first thing most people want to know is: how has their performance been? Thankfully, there’s lots of historical data on the topic.

Tweedy Browne, an investment management firm, reviewed some of this data in What Has Worked in Investing, a meta-analysis of which investment approaches have been the most successful throughout the 20th century. And what did they find?

They found that stocks with higher dividend yields typically outperformed stocks with lower dividend yields across the world. Their finding comes from the paper “The Importance of Dividend Yields in Country Selection” which was published in the The Journal of Portfolio Management in 1991. As they state about the paper’s results:

The study indicated that the most profitable strategy was investment in the highest [dividend] yield quartile. The compound annual investment return for the countries with the highest yielding stocks was 18.49% in local currencies (and 19.08% in U.S. dollars) over the 20- year period, December 31, 1969 through December 31, 1989. The least profitable strategy was investment in the lowest [dividend] yield quartile, which produced a 5.74% compound annual return in local currency (and 10.31% in U.S. dollars).

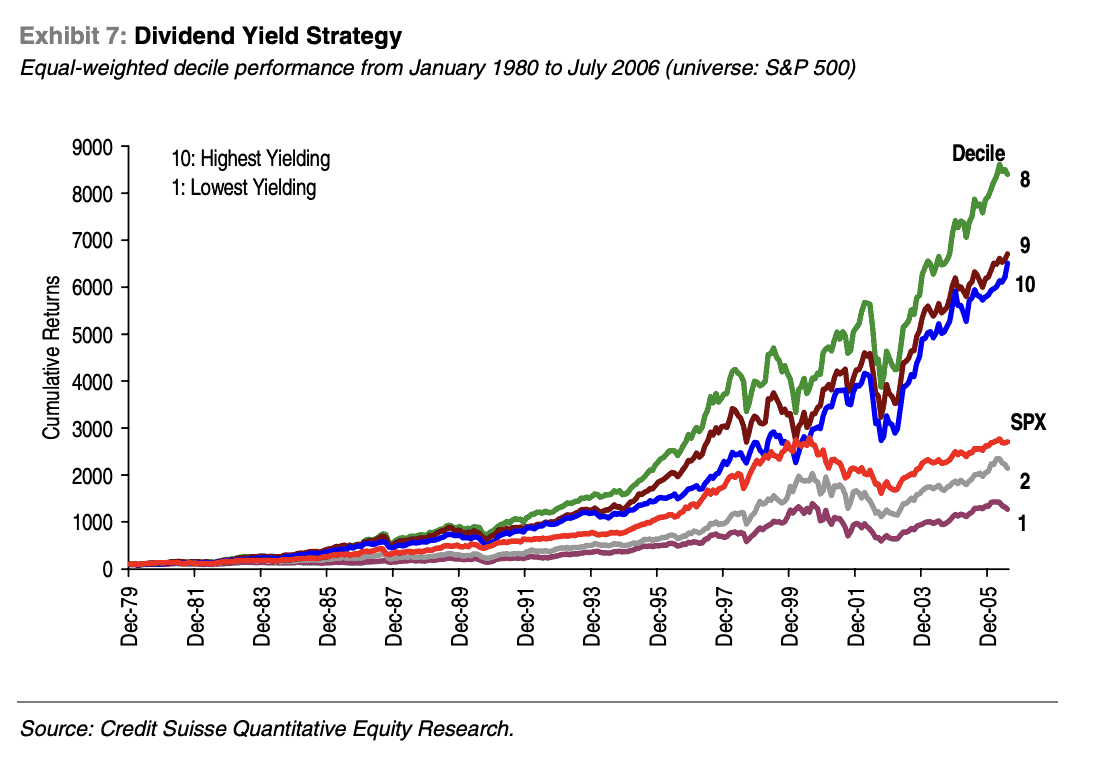

However, this isn’t the only study to have documented this effect. In “High Yield, Low Payout” Credit Suisse’s quantitive equity research team also found that, “stocks with higher dividend yields generally outperformed those with low dividend yields.” However, their backtests found that it wasn’t the absolute highest yielding stocks (10th decline) that performed the best, but those that were slightly below the top (8th & 9th decile):

Either way, this research suggests that, historically, dividend paying stocks have outperformed non-dividend paying stocks. But, is this still true?

Either way, this research suggests that, historically, dividend paying stocks have outperformed non-dividend paying stocks. But, is this still true?

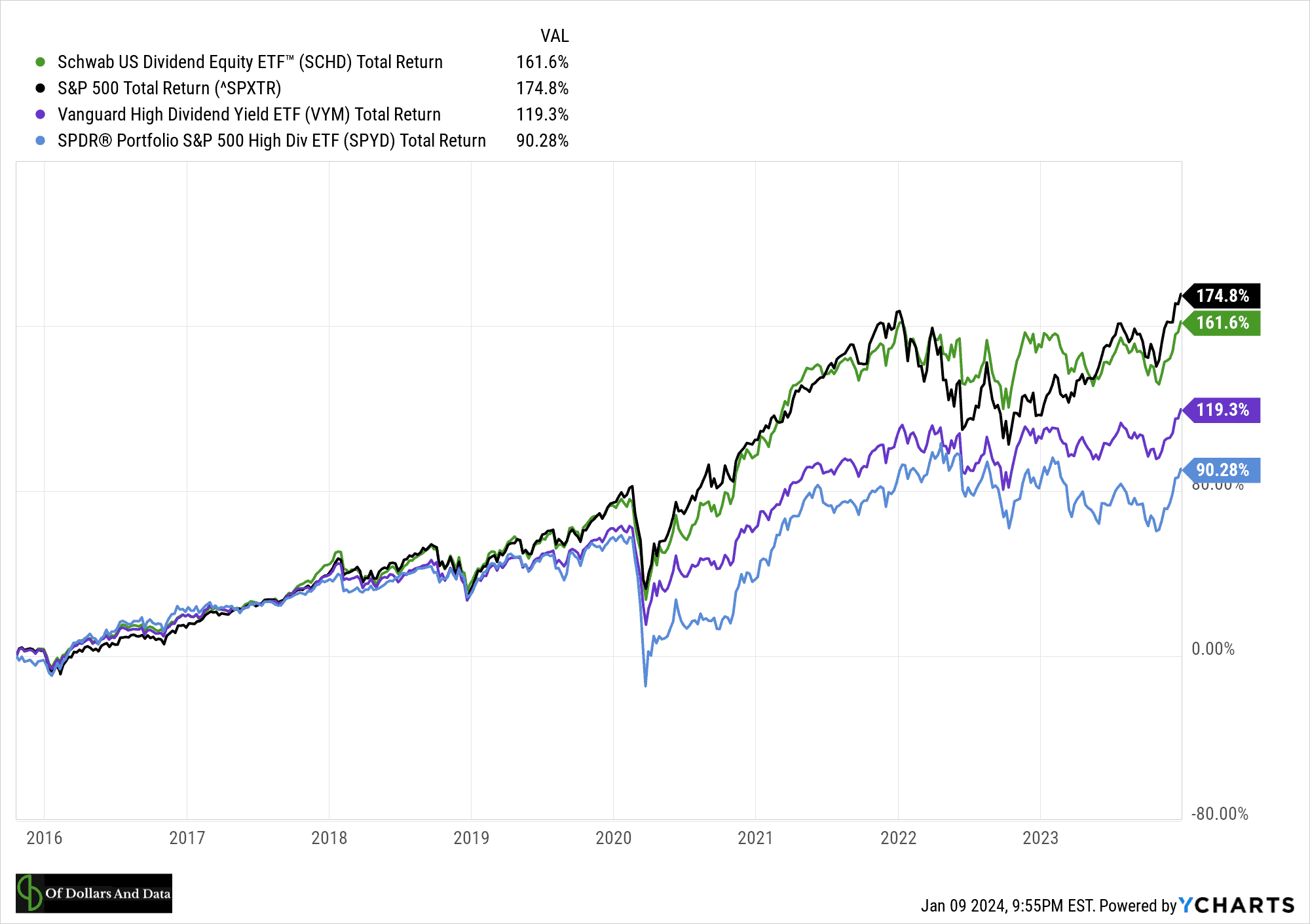

Unfortunately, I don’t think so. Every dividend fund I’ve looked at has underperformed the market (S&P 500) over the last five to 10 years. For example, below is a chart showing the total return of the S&P 500 (in black) against three dividend funds from October 2015 to December 2023:

As you can see, only Schwab’s dividend fund has somewhat kept pace with the market while its two high-yielding counterparts have lagged further behind. While it might be too soon to suggest that dividend paying stocks will no longer outperform non-dividend paying stocks, I have two valid reasons for why this might be true:

- Changes in corporate strategy have favored stock buybacks over dividends

- Changes in the composition of U.S. stocks have favored technology stocks (which tend not to pay dividends)

Let’s take each of these in turn.

First, for the uninitiated, stock buybacks are when a company buys back it’s shares from the public to lower the share count, increase the earnings per share, and, in theory, raise the price of their stock. Economically, this is equivalent to paying a dividend with the only real difference being the tax treatment for shareholders. While shareholders have to pay tax on their dividends when they get them, they don’t have to pay taxes on increases in the share price until they sell their shares.

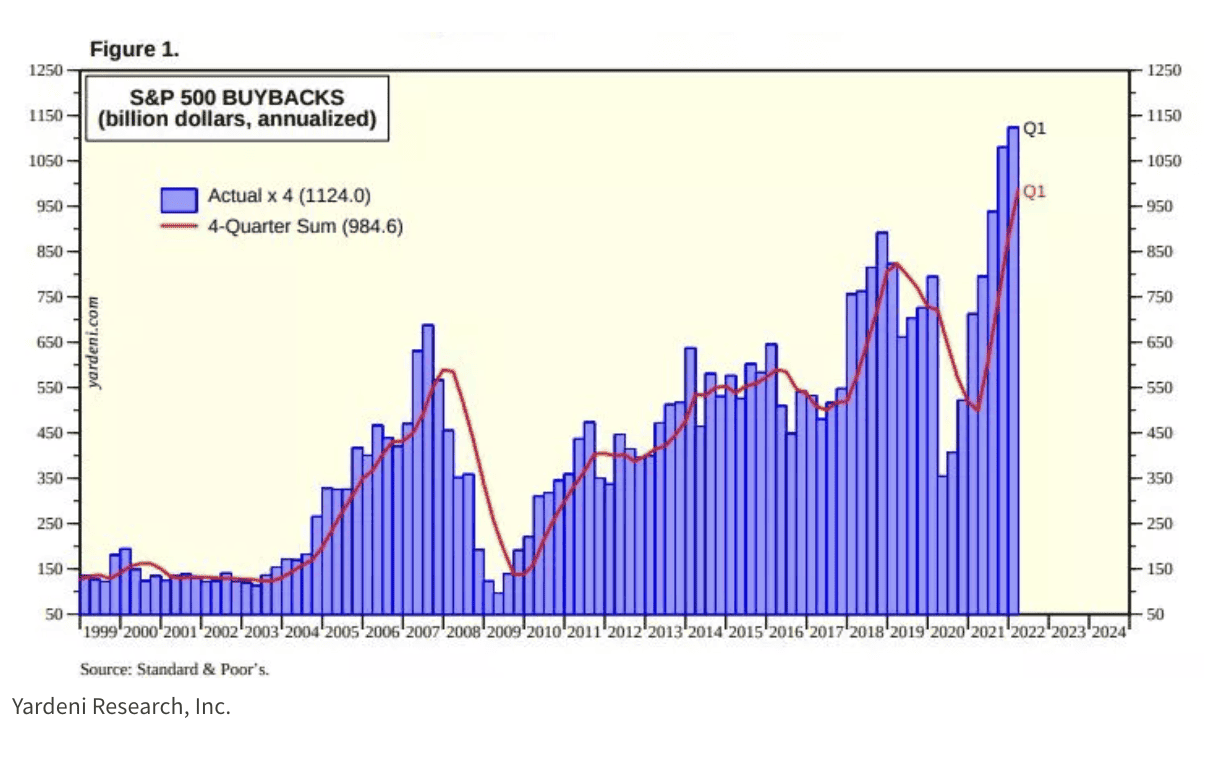

Putting that aside, stock buybacks were more or less illegal in the U.S. until the SEC adopted rule 10b-18 in 1982, which made it easier for companies to buy back their stock. However, it wasn’t until a little after the turn of the century that stock buybacks really took off. As you can see in the chart below from Yardeni Research, stock buybacks hit record levels in recent years:

As a result of this change in general corporate strategy, many companies that would have traditionally paid dividends (and been high performers historically) are now buying back shares instead. This means fewer companies are paying out dividends like they used to, which could make investing in dividend paying stocks less appealing.

Second, changes in the composition of the U.S. stock market toward technology companies has reduced overall dividends as well. Since many tech companies typically make little to no profits for an extended period of time as they scale, they can’t pay out dividends to their shareholders. And since technology companies have been so dominant in the U.S. over the past decade, you can see why dividend paying stocks haven’t been able to keep up.

Ultimately, the result of shifting corporate strategy and changing stock composition means that the dividend paying stocks of today aren’t what they used to be. Despite these changes, dividend paying stocks can still be appealing for a host of reasons. Let’s look at some of those now.

The Appeal of Dividend ETFs

There are two primary reasons why you might consider owning dividend ETFs—stability and psychological comfort.

Dividends Are More Stable than Prices

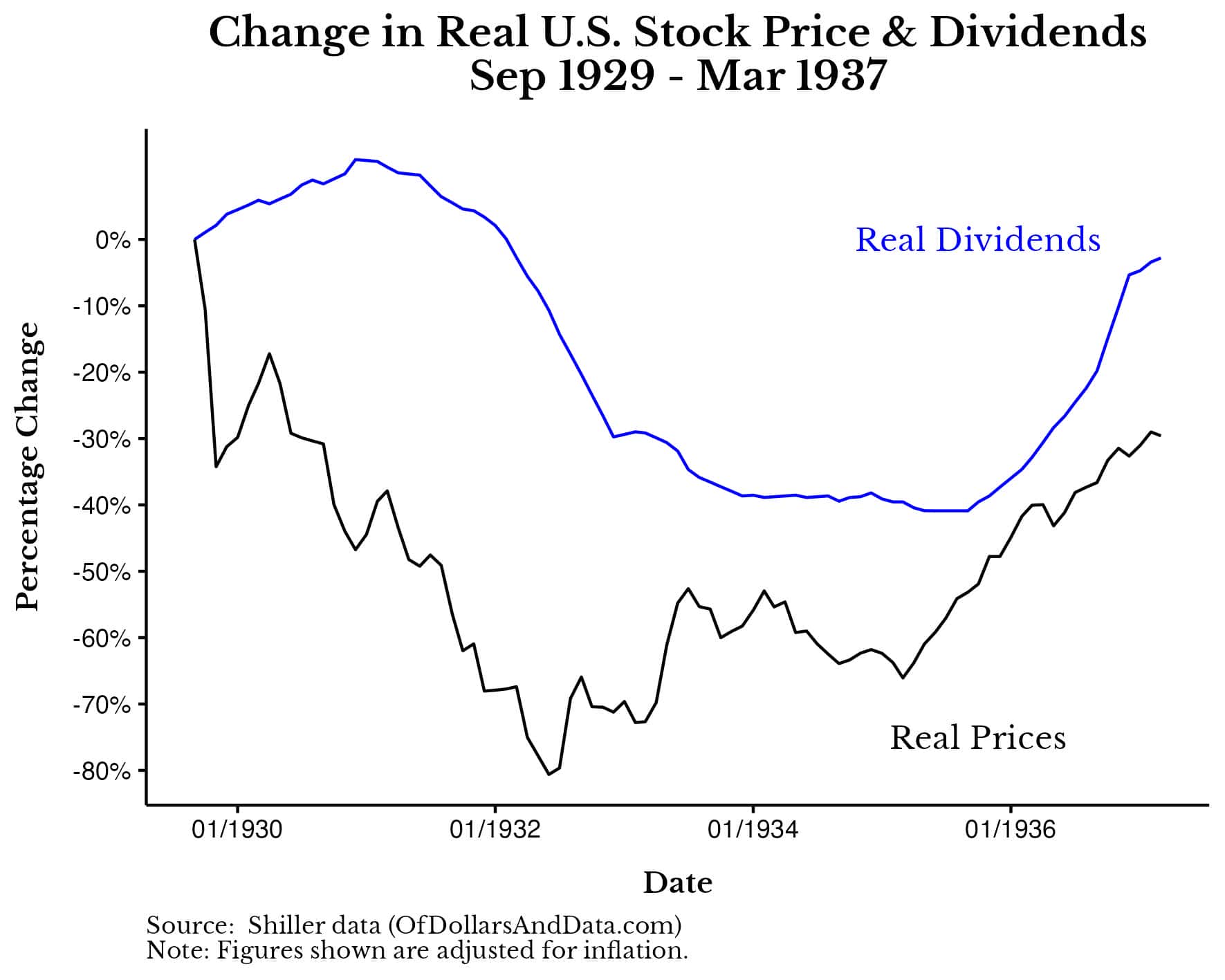

Unlike stock prices, which move based on the whims of market participants, dividends are set by company management and have been far more stable than prices historically. My favorite example of this comes from The Great Depression where monthly prices declined by nearly 90% (from peak to trough) but dividends weren’t even cut in half.

You can see this in the plot below, which relies on Robert Shiller’s U.S. stock market data. Note that this chart shows a real price decline of only 80% and a real dividend decline of only 40% because Shiller uses monthly data, which is less precise than daily data:

From the peak in September 1929, real prices bottomed in less than three years, but it would take another three years before real dividends hit their lows.

The stability of dividends during the darkest period in American economic history is a testament to their attractiveness. Though The Great Depression was a terrible time for any investor, those that owned dividend paying stocks had a far better experience as they saw their income decline by far less than the price of their holdings. This fact brings us naturally to our next section.

Psychological Comfort

Of all the reasons why people might prefer owning dividend paying stocks, psychological comfort tops the list. Given the higher stability of stock dividends (relative to stock prices) mentioned in the prior section, you can see why investors value their quarterly dividends. There’s something about getting paid to hold stocks that can make the experience seem more real than a number increasing on a screen.

Of course, the counter argument you will hear from investors who own non-dividend paying stocks is that you can always sell your shares to create the dividend income yourself. This is true, all else equal.

However, when prices are crashing, it will become very difficult psychologically to sell your shares to create this income. After all, who wants to sell at a loss, especially a major one?

As I illustrated above, since stock dividends tend to decline by less than stock prices during market crises, you don’t have to deal with this internal conflict as a dividend stock investor. So while, mathematically, non-dividend paying stocks and dividend paying stocks should be equivalent in normal times, I am quite confident owning them during a major crash feels quite different.

Now that we’ve reviewed the benefits of owning dividend paying stocks/ETFs, let’s explore some of the downsides.

The Case Against Dividend ETFs

Though dividends are less volatile than prices and can provide investors with a sense of psychological comfort, there are a few reasons why you might want to avoid them.

Tax Inefficiency

When you get paid dividends from a company those dividends are either qualified or non-qualified. This distinction matters because qualified dividends are currently taxed at the long-term capital gains rate (around 15% for most investors), while non-qualified dividends are taxed like income (typically higher than 15% for most investors).

Technically, most dividend ETFs are pretty good about ensuring that all dividends they pay out are qualified and, thus, at the lower tax rate. For example, if you review Vanguard’s or Schwab’s qualified dividend income figures across their funds, you will see that the ones that focus on dividends specifically tend to have 100% of their dividend income as qualified dividends. This is good for dividend investors.

That aside, dividends (whether qualified or not) still generate taxable income for investors that stock buybacks do not. When a company buys back its own stock, it does not send cash to shareholders and, therefore, does not create a taxable event. Instead, the theory states that the price of the stock should rise after the buyback giving shareholders the option to sell on their own terms. For this reason alone, some investors may want to avoid those companies that pay dividends (rather than do buybacks).

Sector Concentration

As I mentioned above, due to changes in the composition of the U.S. stock market, dividend paying stocks are fundamentally different from non-dividend paying stocks today. Therefore, by loading up on dividend stocks/ETFs, you are inherently making a bet on companies in the sectors that tend to pay the most dividends (e.g. utilities and real estate).

If you are okay with doing this, that’s fine, but I feel like many dividend investors chase after dividend income without realizing how they are re-positioning their portfolio in the process.

Out of Touch Management?

While historically, dividends were a way for a company’s management to send money back to shareholders, with the rise of share buybacks (and their increased tax efficiency), there’s a debate as to whether dividends are still the best use of a company’s capital.

I’m definitely not an expert on this issue, but if a company’s management is paying dividends (instead of doing buybacks) some may view this as out of touch with modern corporate strategy. Of course, there are still good reasons why a company’s management might prefer paying dividends over doing buybacks despite the subpar tax efficiency of dividends:

- Buybacks are political. Though I discuss buybacks and dividends as if they are interchangeable, there is a cohort of people who believe buybacks should be illegal. While I do agree that buybacks can be misused to enrich management (over shareholders), I don’t think buybacks are the primary issue here. Rather than getting bogged down in this debate, let’s just say that some companies avoid buybacks for PR reasons.

- Dividends are traditional (and more stable). If a company has a long tradition of paying dividends, switching to buybacks may upset existing shareholders. In addition, unlike buybacks, which can vary over time based on a stock’s price, dividends can be more stable.

- Dividends enhance financial discipline. Paying regular dividends imposes discipline on a company’s financial management forcing them to be more selective about the projects they invest in.

So while dividends are somewhat less tax efficient than buybacks, I can see why some companies still rely on them.

Now that we’ve looked at the case against owning dividend paying ETFs, let’s wrap things up by summarizing who should and shouldn’t buy dividend ETFs.

Who Should (And Shouldn’t) Consider Dividend ETFs

As we wrap up our discussion on dividend ETFs, it’s important to consider who stands to benefit most from these investments, and who might be better off looking elsewhere. Ultimately, whether you decide to own a dividend-focused ETF should be based on your financial goals, time horizon, and personal preferences. Below is a summary of who should (and shouldn’t) consider buying dividend-focused ETFs.

Who Should Consider Dividend ETFs

- Income-Focused Investors: If you’re seeking a consistent income stream, particularly in retirement, dividend ETFs can be a valuable part of your portfolio. Note that you can technically re-create an income stream of non-dividend paying ETFs by selling them down each quarter, but some people don’t like the idea of selling down their portfolio, which is why dividend ETFs can seem more appealing.

- Investors Preferring Stability: Those who are more risk-averse may find comfort in the stability that dividend-paying stocks tend to offer, especially during volatile market periods.

- Investors Who Like Dividends: There is a certain level of psychological comfort that dividends can provide (outside of their stability). If you find yourself liking the idea of getting quarterly payouts from your portfolio, then dividend-focused ETFs might be right for you.

Who Might Want to Avoid Dividend ETFs

- Growth-Oriented Investors: If your primary goal is capital appreciation, not income, then growth-focused ETFs might better serve your needs.

- Investors in Higher Tax Brackets: Given the potential tax inefficiencies associated with dividends (compared to stock buybacks), those in higher tax brackets might want to avoid dividend-focused ETFs.

- Investors Seeking Maximum Diversification: If you want broad market exposure, then you might want to stay away from dividend ETFs which have sector concentration risks particularly within utilities and real estate.

While dividends have been a great bet historically, today they seem better suited for someone who has a specific need for them. Either way, I hope you found this guide on the topic helpful.

Happy investing and thank you for reading!

If you liked this post, consider signing up for my newsletter.

This is post 387. Any code I have related to this post can be found here with the same numbering: https://github.com/nmaggiulli/of-dollars-and-data