I recently read a blog post from Patrick Stanley where he claimed:

By the end of this decade, almost everyone who’s online will become an investor.

I agree with Stanley’s assertion, but what he is describing has mostly already happened. Over the last few hundred years, and especially over the last half century, investing has evolved from something only done by the rich and powerful to something done by everyday people. And given how much access has expanded in recent years, the entire world is slowly being brought into the investment fold. We are all investors now.

So, how did this happen? And, more importantly, what will the future of retail investing look like? Let’s dig in.

The First Investment in Human History

Before we can examine the future of investing, we must first understand the history of investing. And, I believe, the history of investing starts with food preservation.

Before the advent of agriculture, food preservation was one of the only ways in which people could invest toward their future. The image below showing Native Americans preserving Buffalo meat for future consumption is one such example of this:

The act of sacrificing food today in order to have food tomorrow is the simplest (and oldest) form of investment we know. Unfortunately, these investments only lasted a few weeks to a few months at best.

It wasn’t until agriculture took hold in human civilization that investing for the future became far more involved. With increased surpluses of food and resources, farmers, and eventually, rulers could determine what and how much to save for the future. For example, during Roman times, a warehouse known as a horreum would be used to store grain and other food supplies:

While saving for the future was starting to become more commonplace, it was still done mostly among the ruling elite. Most people didn’t really have a way to invest. However, this started to change in the Middle Ages.

The Rich Investment Boom

Imagine you are a merchant living in Venice in the 1500s. You are in a port city that is bustling with trade, however, you don’t have enough money to personally finance a sea voyage to bring back exotic goods for you to sell. What do you do? Enter the commenda.

As Marc Rubinstein stated in his wonderful piece on the history of private equity:

The commenda was used to finance merchant shipping. Passive investors would put up most of the capital and share in the profits of the voyage. In a downside scenario, they couldn’t lose more than they’d put in—their liability was limited.

The commenda, for all practical purposes, was one of the first examples of investors pooling their capital in hopes of returning a future profit. Given the risks (and possible rewards) associated with sea expeditions, you can see (pun intended) how the commenda took off among those with investable capital.

These initial contracts eventually gave way to the Dutch East India Company, founded on the Amsterdam stock exchange in 1602. The Dutch East India Company was the first publicly-traded company in history and was granted a monopoly on the Dutch spice trade with India. With the founding of the Dutch East India Company, anyone with wealth could now invest their money. No longer did you need to be in a position of power or have any particular connections if you wanted to invest.

While this was a revolutionary event for investors around the world, it still doesn’t explain what created today’s retail investor. For that we turn to our next section.

The Birth of the Retail Investor

Two hundred years ago the modern day retail investor didn’t exist. Why? Because they were likely dead.

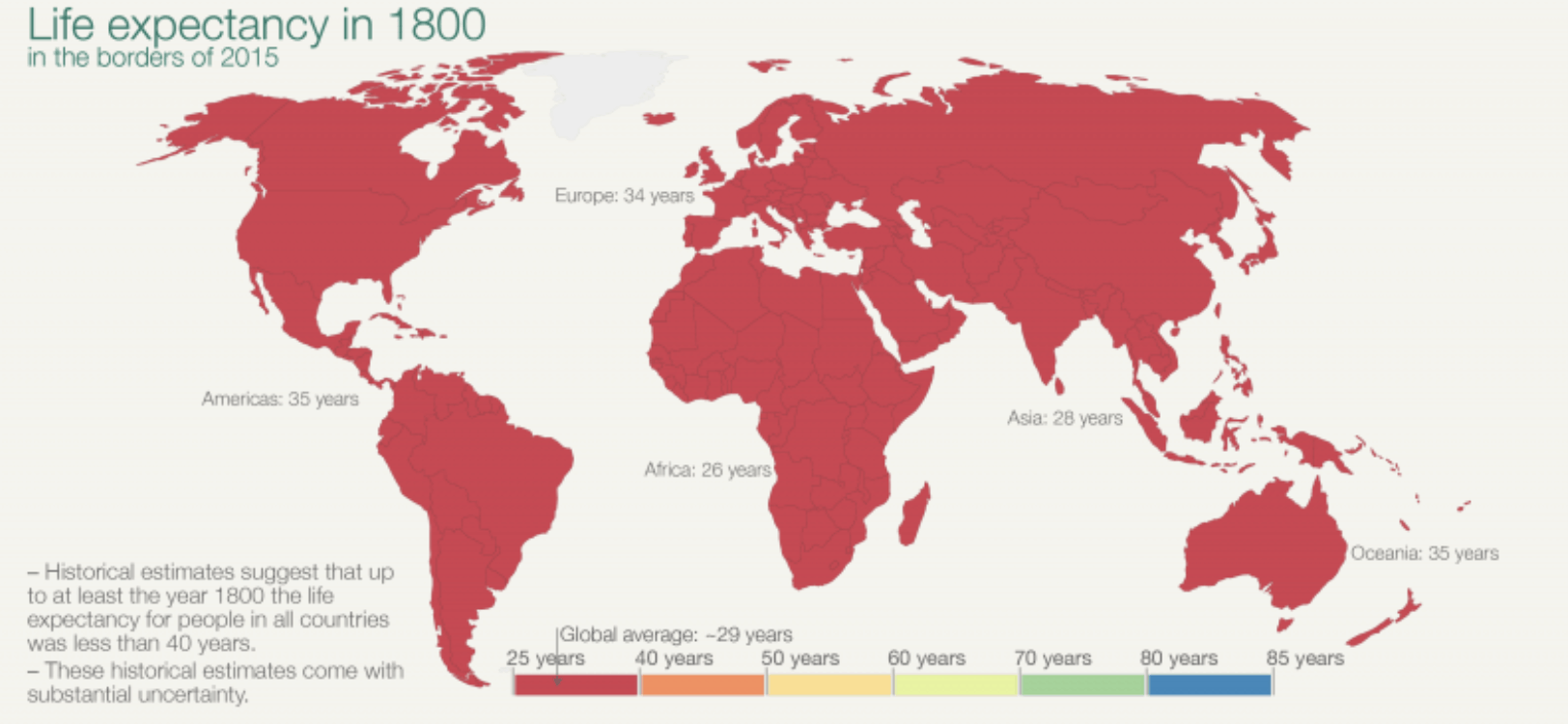

What I mean is that most people didn’t live long enough to ever have the need to invest. If you look at life expectancy across the globe in 1800 you can see what I mean:

For most of the world, life expectancy was in the 20s and 30s, with a global average of 29 years. As Thomas Hobbes so eloquently stated, for most of history humans had lives that were “nasty, brutish, and short.”

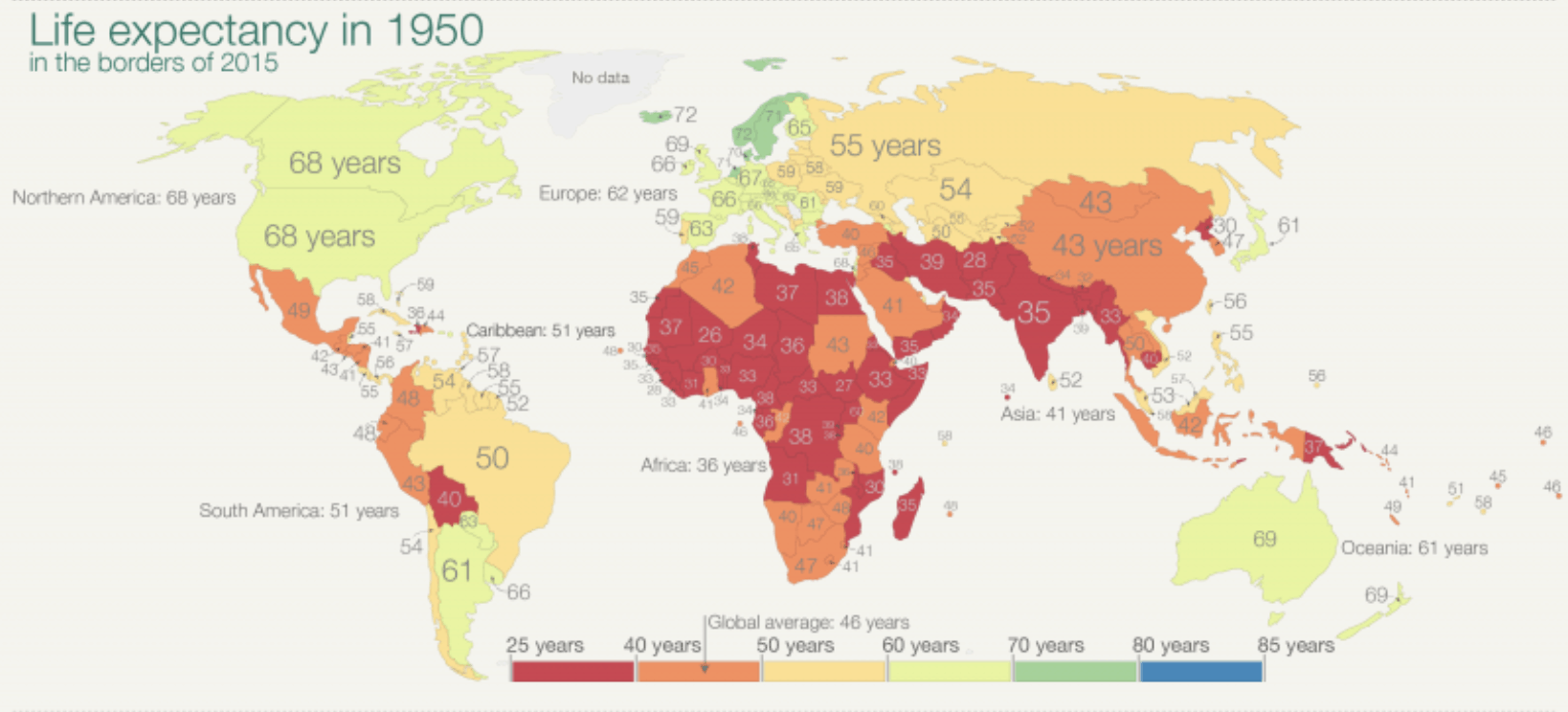

But look at what happened over the next 150 years of human history. It’s remarkable:

Only a century and a half later and the global average for life expectancy had increased to 46 years with some countries reaching into the 60s and 70s. The advent of modern medical technology (sanitation, vaccines, etc.) had come to extend life in unforeseen ways.

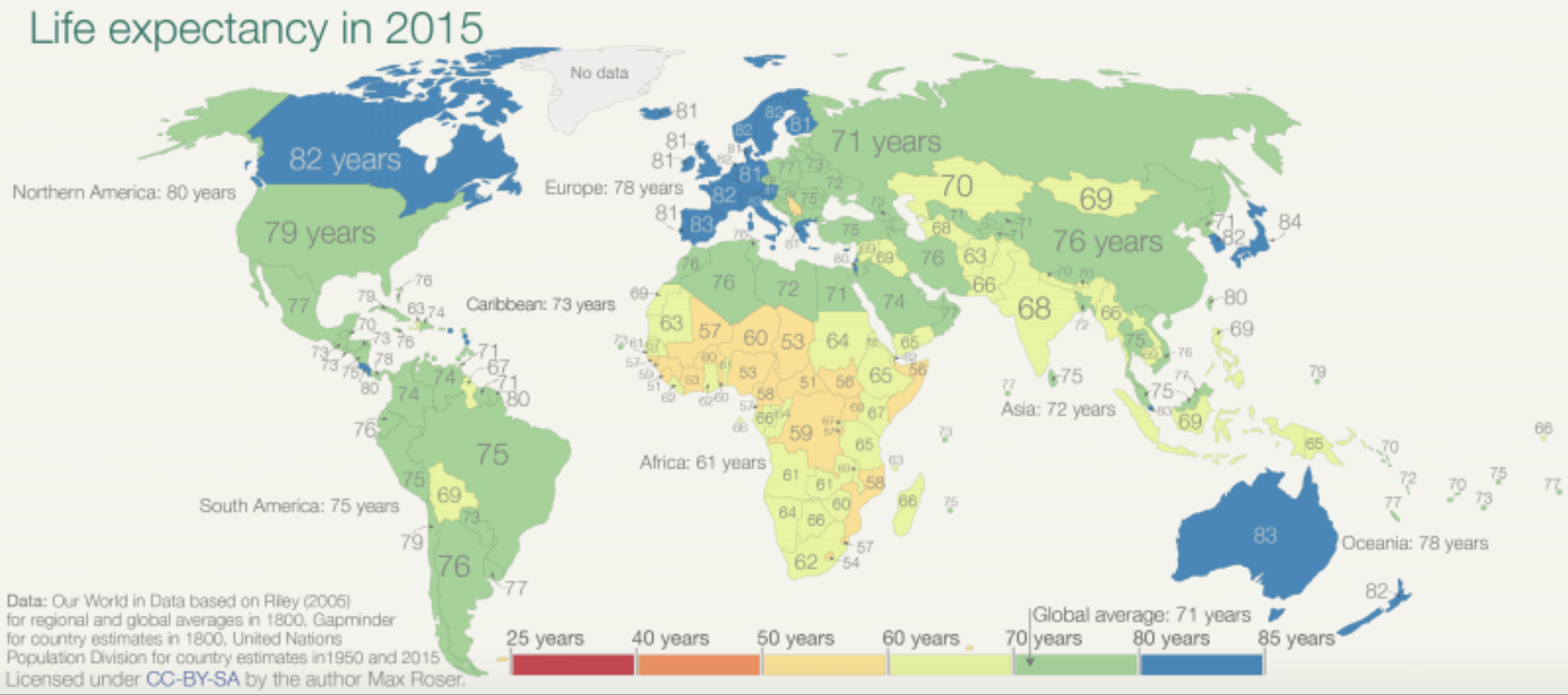

As these changes proliferated around the world over the next six decades, global life expectancy increased to 71 years (on average) by 2015:

In the span of two centuries we went from a world where life was “nasty, brutish, and short” to one where old age was a near certainty for most people around the world.

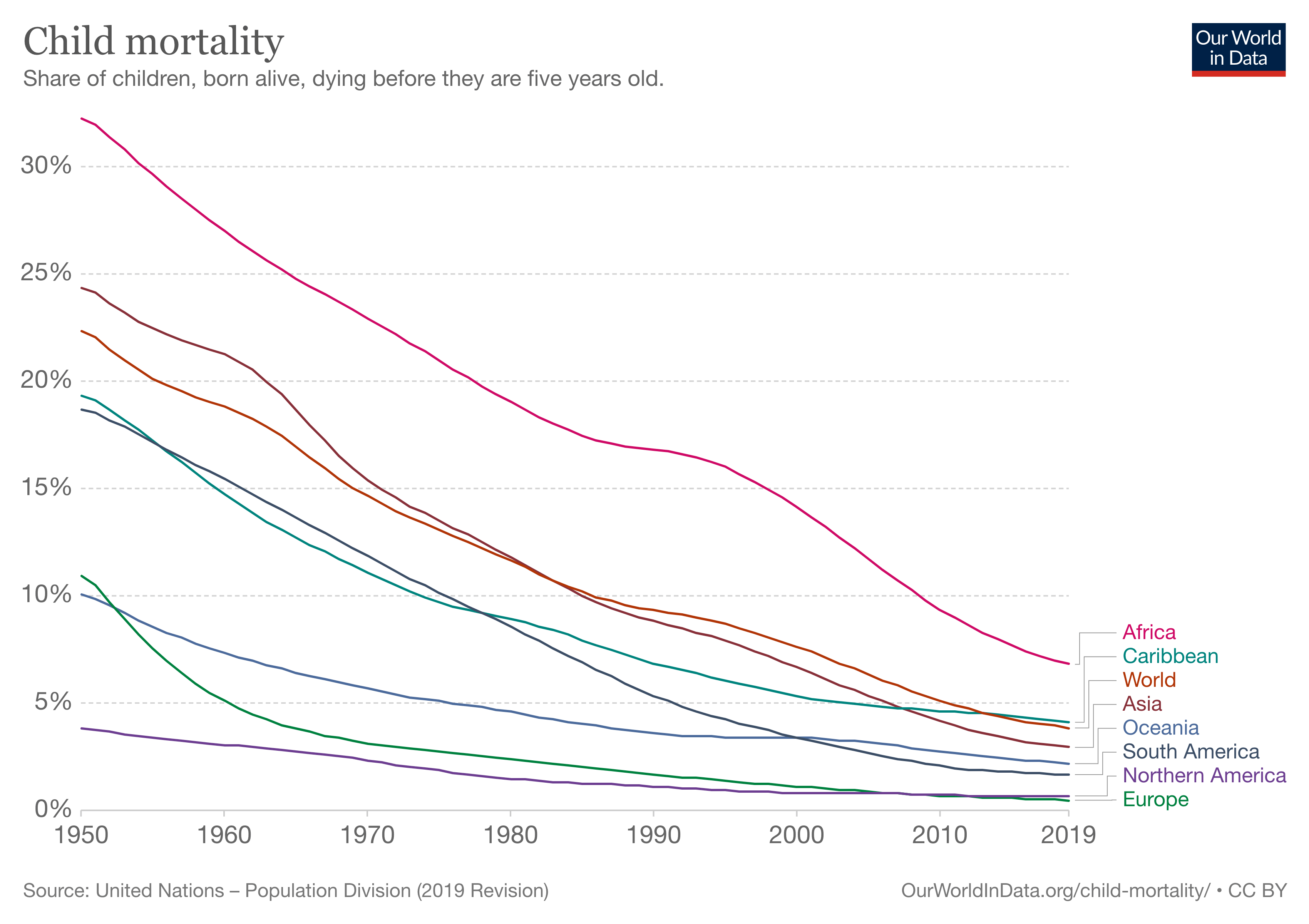

There is a slight caveat with this analysis though. A large part of the increase in life expectancy is the drop in childhood mortality. As evidenced by the chart below, the number of children dying before age five has decreased dramatically around the world:

But, that isn’t the entire story. Yes, childhood mortality is driving a lot of the changes in life expectancy, but lifespans have also increased considerably over this time as well.

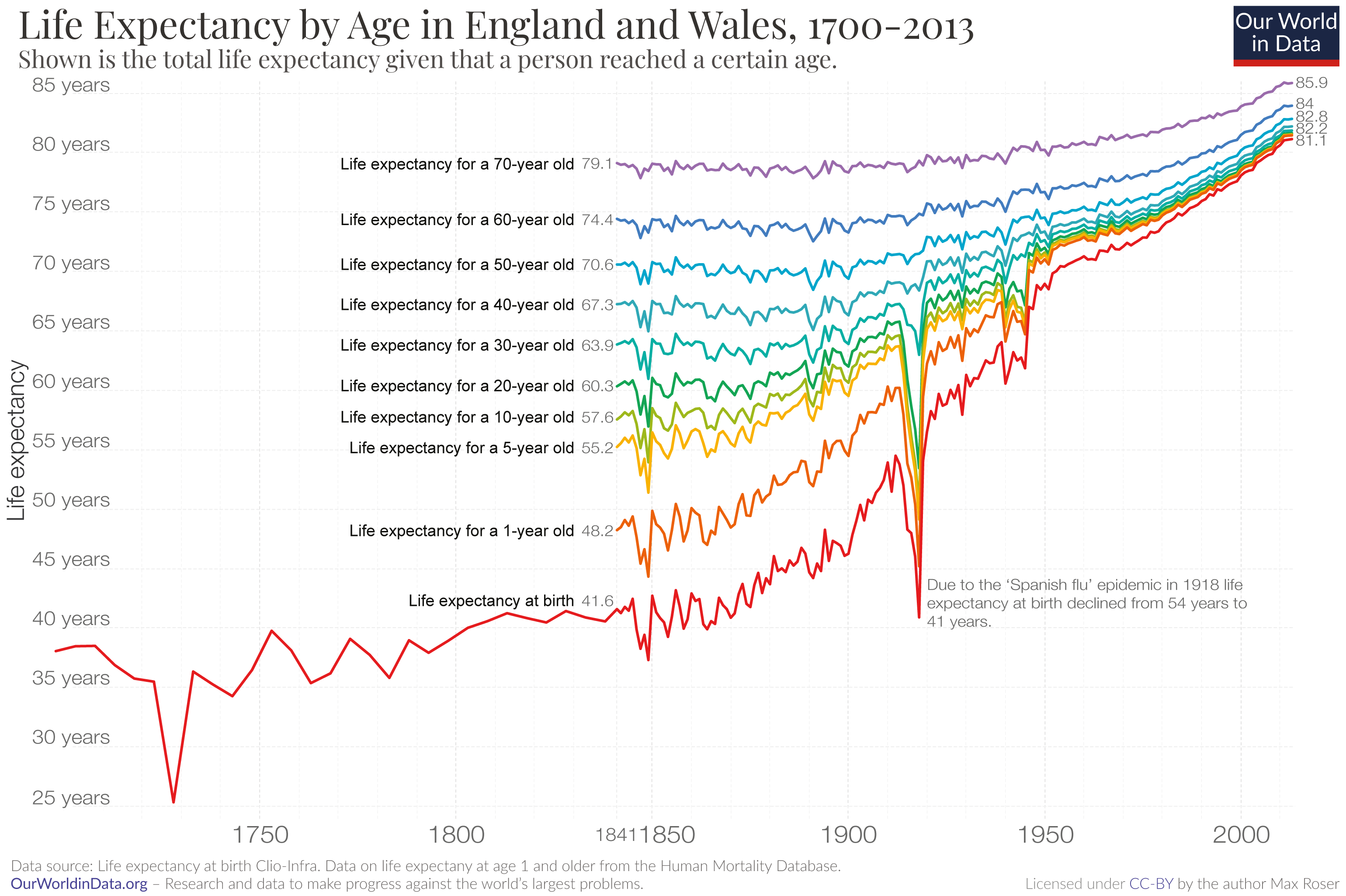

For example, if you look at the data on lifespan coming out of England & Wales, you can see that every age group has been living longer over the last 150 years (with a brief exception during the Spanish flu):

This chart shows the life expectancy over time conditional on having reached a certain age. For example, in 1841 the life expectancy of a newborn was 41.6 years. However, if you made it to age five, you could expect to live to 55.2 years of age.

The two important things about this chart is that all the lines are moving up and to the right (increasing lifespan) and the spread between the lines has come down over time (i.e., childhood mortality has dropped). In particular, I want you to focus on the yellow line above, which shows the life expectancy for a five year old over time. In 1841 a five year old could expect to live to 55, but by 2013 they could expect to live to 82.

That is roughly 30 years of extra life that people in England & Wales have today that they wouldn’t have had a few hundred years ago!

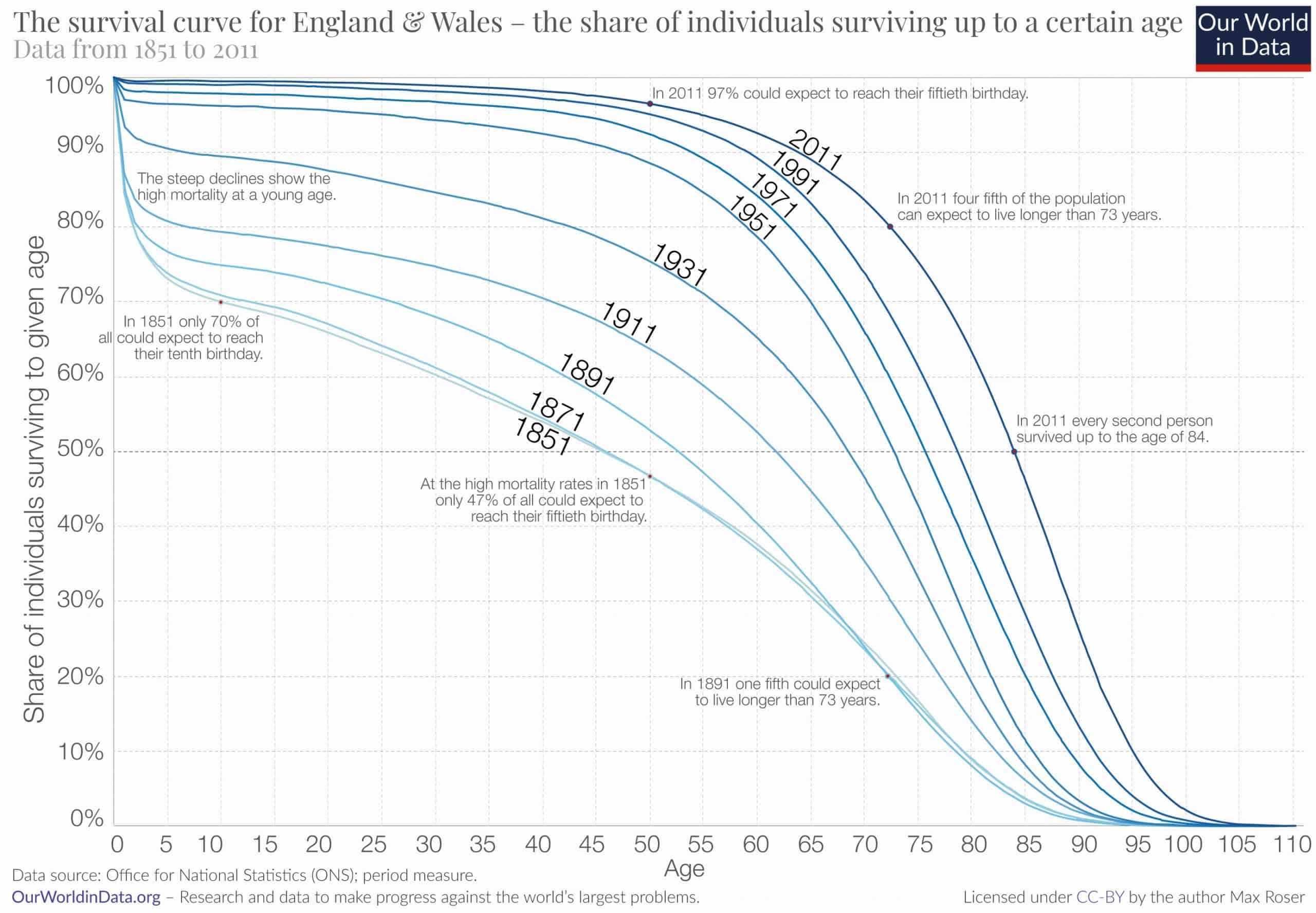

You can see this more clearly if you look at survival curves in England and Wales over this same time period:

What this chart shows is the percentage of individuals making it to a certain age at a certain period in time. For example, in 1851 only about 25% of people made it to age 70. However, by 2011 that number was 85%.

It is no coincidence that these extra decades of life have been met with an increased demand for investing. With more certainty about the future, people today have a higher need for investment services that will allow them to live more comfortably in old age.

This is how the retail investor was born. Without the medical advances over the last few centuries, old people would not exist as a sizable cohort today. However, because they do exist, investing is needed more than ever.

Nevertheless, while the revolution in health and medicine gave birth to the retail investor, it was the rise of cheap diversification that matured them.

The Rise of Cheap Diversification

If you wanted to invest in U.S. businesses in 1920, you didn’t have many options. You either had to buy the businesses yourself or purchase individual stocks. While there is nothing wrong with doing either of these, both strategies can be quite risky and expensive (at least historically).

It was until the invention of the mutual fund in the 1920s and the index fund in the mid-1970s that diversification became easier for the average investor to acquire. However, it wasn’t necessarily cheap. Between load fees and transaction costs, getting a diversified portfolio was far more costly than it is today.

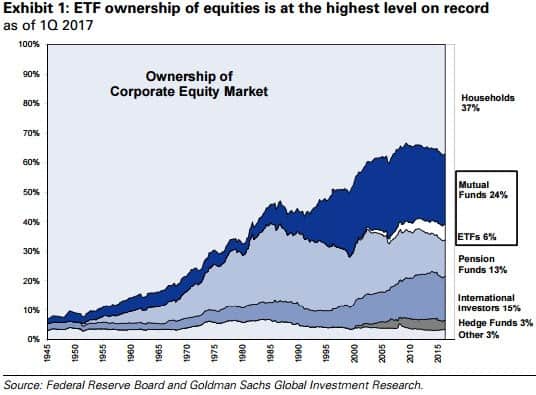

However, as costs came down, the amount of assets in diversified investment vehicles increased. You can see this most clearly when looking at ownership of U.S. equities over time by owner type:

Though households used to own 90% of U.S. common stock in 1950, today they only own 37%. Why did their share drop? Not only have international investors and pension funds bought up more of the market, but mutual funds and ETFs now collectively own 30% of U.S. equities. More importantly, most of that gain in market share has come since 1985.

While I could go into the details of how this all happened, this is a blog after all and you get the point. Technological changes that allowed for increased market efficiencies have made it cheaper than ever to get access to a broad basket of equities (from around the world). It’s gotten to the point where you can now own a globally-diversified portfolio for less than 0.2% per year.

This is where we stand today. Cheap diversification sits at the modern retail investor’s fingertips. But what comes next?

Where Do We Go Now?

Everything I have presented thus far has been based around historical evidence and fact. Unfortunately, this section diverges from that trend. When it comes to figuring out the future of retail investing, we have no history to rely on. Therefore, we have to make educated guesses about what will come to pass. In doing so, I’m reminded of the old phrase that goes:

It is difficult to make predictions, especially about the future.

With that being said, I believe that the future of retail investing will be one of mass customization. We will look back on an era when everyone owned the S&P 500 in its exact proportions as archaic and backward. The fact that a school teacher, a financial services professional, and an oil worker all could own the same set of equities seems absurd to me.

Why would these people take the same equity risks in their portfolios when their careers have very different risk profiles? For example, if you work in finance shouldn’t you have less exposure to financial stocks than everyone else? After all, your career is already exposed to financial markets, so wouldn’t it be better to hedge away that exposure in your portfolio? The same logic applies to someone who works in tech and in every other sector.

Unfortunately, creating a portfolio that is specific to your life isn’t necessarily cheap or easy today. But one day it will be. There are some firms that can do this kind of work using customizations on direct indexing, but not many. More importantly, these kinds of offering are usually reserved to high net worth investors only.

One of the products that I am most familiar with is Custom Indexing by OSAM. [Disclaimer: My firm has an ongoing relationship with OSAM and we use their investment products.] The idea behind custom indexing is quite simple, you create a portfolio that is custom to your specific circumstances.

Work in the energy sector? Imagine owning the S&P 500 but down-weighting energy stocks.

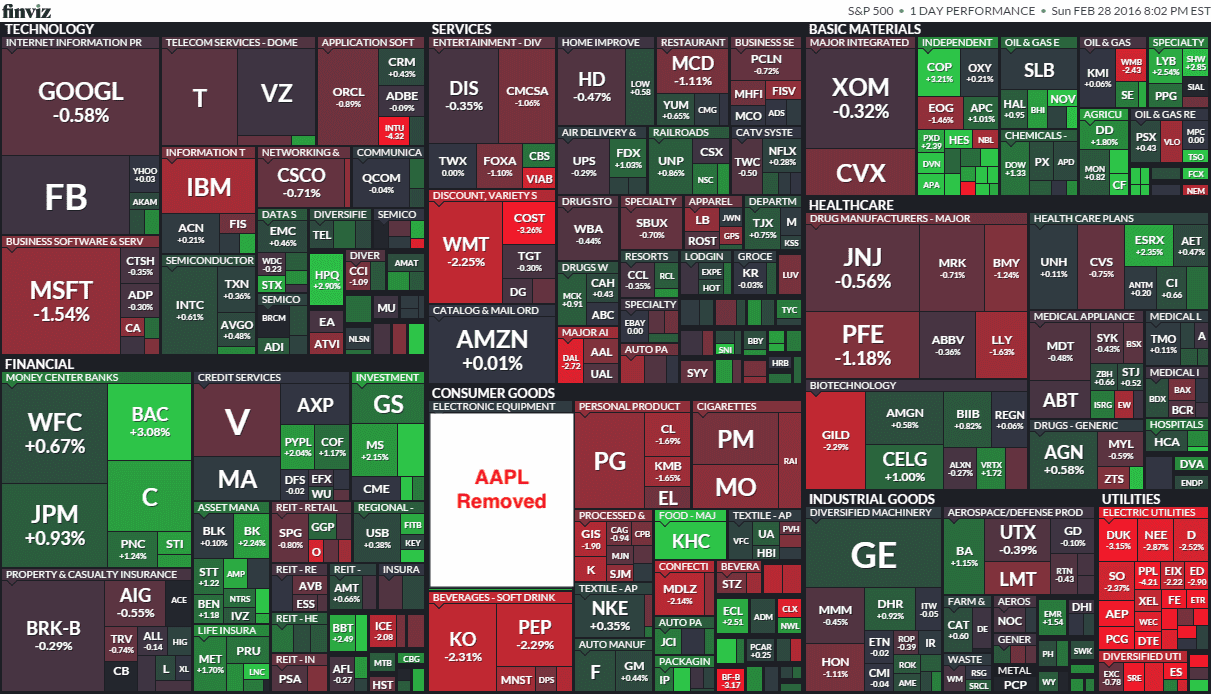

Have a huge Apple position and can’t sell it for tax purposes? No problem. Let’s create you a portfolio that is the S&P 500 ex-Apple:

The implications of this technology are just now being understood, but I think it’s a game changer.

This will be especially true once it is no longer a premium product and it is cheap enough for everyone to use. Once we get there, why wouldn’t we all have custom portfolios? Why not have investments that better fit the entirety of our risk profile? It just seems like a no brainer to me.

I’m not the first to make these claims either. My boss and fellow blogger Josh Brown, called for this in December 2020 and recently doubled-down on his belief that custom indexing is the future.

Of course, Josh and I could be wrong because we are too close and familiar with the technology to see this objectively. However, I see this as the next logical step in the evolution of the retail investor. Not only are we all investors now, but the investment industry is starting to cater to us, as individuals.

You will no longer have to be well-connected or powerful or rich to get access to the portfolio that is perfect for you. Unfortunately, that day isn’t here just yet, but one day it will be.

If you liked this post but want an audio/video version of it, I gave a similar talk earlier this year for GBM, a financial services firm based in Mexico. Thank you for reading!

If you liked this post, consider signing up for my newsletter.

This is post 251. Any code I have related to this post can be found here with the same numbering: https://github.com/nmaggiulli/of-dollars-and-data