I’ve always liked the idea of living in the penthouse. The view. The luxury. The lack of noisy upstairs neighbors. There’s something exciting about it. And, as someone who has lived in eight different apartments over the past 11 years, I understand why people pay a premium for the experience.

But things weren’t always this way. In fact, throughout most of history, those who lived on the higher floors of a building were typically poorer than those who lived down below. When high-rise construction took off in the early 1900s in places like Manhattan, elevators weren’t yet commonplace. This meant that those living on the upper floors had to climb more stairs every time they came home. This was a major inconvenience that wealthier residents (living on the lower floors) paid to avoid.

But convenience wasn’t the only issue at hand. Which floor you lived on could also be a matter of life and death. In ancient Pompeii, where most homes were built out of wood, living on a higher floor meant an increased chance of dying during a fire. This is one of the reasons why wealthier residents lived on the ground floor, where they could more easily escape such a blaze.

I’ve always found it intriguing how money impacts the non-financial aspects of our lives. How it affects where we choose to live or what kinds of risks we take. And the older I get, the more I’m convinced of its importance.

I don’t say this because of what money can buy directly, but what it can buy indirectly. I’m talking about things like a better education which can lead to a better career, higher lifetime earnings, and, ultimately, more wealth.

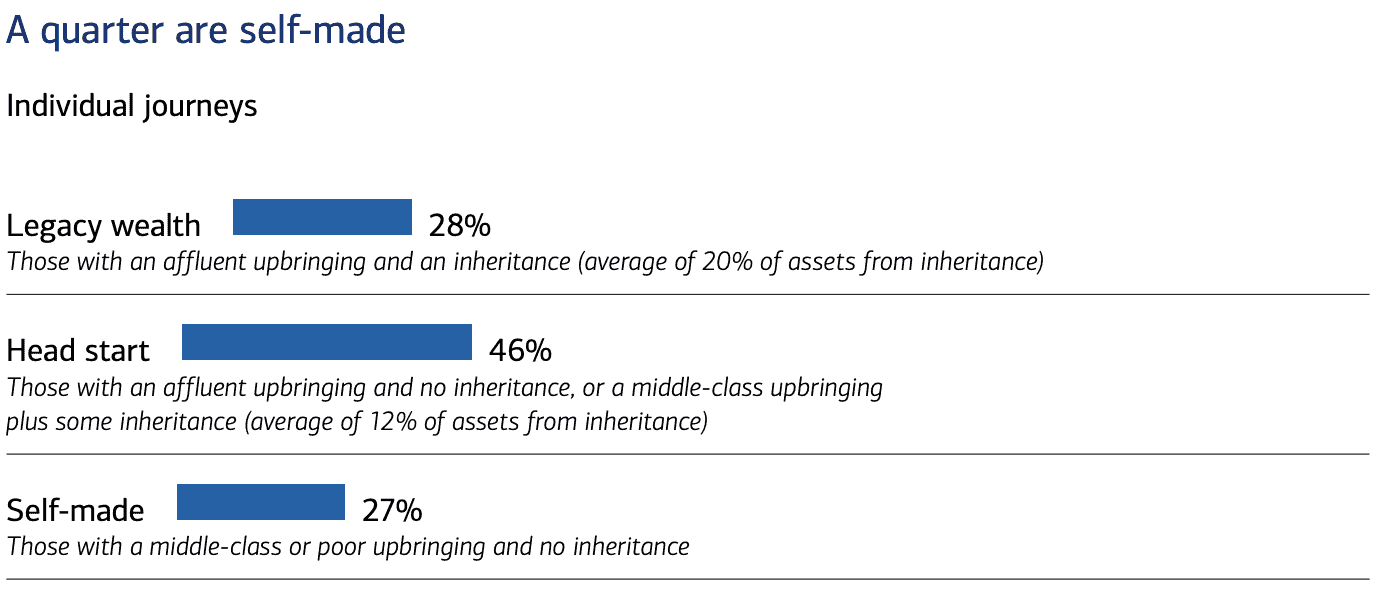

This partially explains why only 1 in 4 people with over $3 million in investable assets are self-made, according to this 2022 Bank of America study:

As you can see, most people with over $3 million in investable assets had some sort of monetary advantage early in life, either via an inheritance, an affluent upbringing, or both.

Though there are people like Howard Schultz who grew up poor and ended up becoming a multi-billionaire (thanks to Starbucks), these success stories are the exception, not the rule. For every Howard Schultz who grew up in poverty, there is a Jeff Bezos, a Mark Zuckerberg, and a Donald Trump who didn’t.

I mention Bezos, Zuck, and Trump, because they all had some parental involvement in their early business endeavors either through loans or direct investments into their companies. This isn’t meant to discount the hard work they put into their businesses, only that it’s a bit easier to take such risks when you have a significant financial safety net.

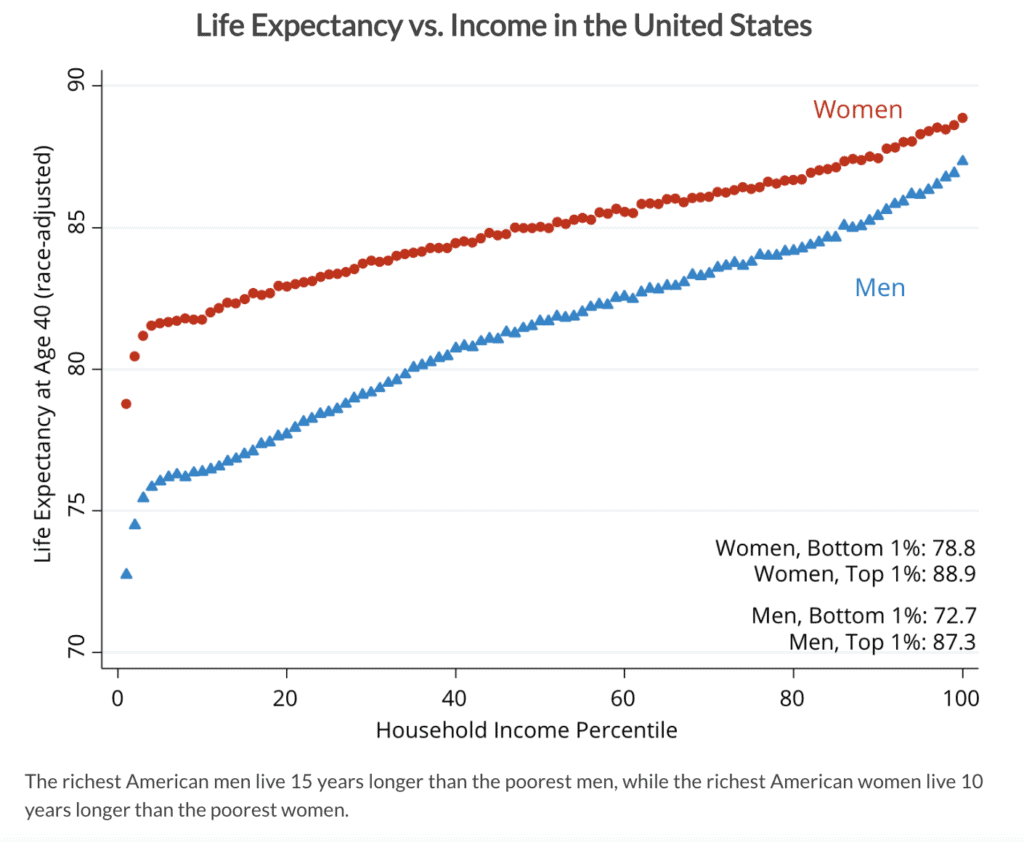

But, money can indirectly influence more than just your career. It can have a dramatic impact on your life expectancy as well. The Equality of Opportunity Project has data demonstrating this. As their plot below highlights, life expectancy tends to be positively correlated with household income for both men and women:

What’s most interesting about this chart is that life expectancy continues to rise all the way up the income spectrum. One might expect this relationship to plateau at a certain income level, say at the 90th percentile, but it doesn’t.

Of course, people higher on the income scale likely differ from people lower on the income scale in some key ways that impact life expectancy. For example, diet, exercise, and other consumption patterns have been shown to be correlated with income, so it probably isn’t higher income by itself that causes the higher life expectancy, but what that higher income represents (i.e. the ability to buy healthier food, etc.). Regardless of what is causing the relationship between income and life expectancy, the important part is that this relationship exists in the first place.

Vicki Robin and Joe Dominguez highlighted the connection between money and well-being in their book Your Money or Your Life (where this blog post gets its title from). However, instead of focusing on life expectancy, they examine how money acts as a form of stored “life energy” that you must manage with care. They argue that failing to do so will result in you sacrificing your life (in terms of time, happiness, and values) in return.

I love this idea because it challenges you to re-think how you spend your money. For example, if you make $50 an hour (after tax), consider whether a $200 dinner in NYC is worth 4 hours of your life. Maybe. Maybe not. If you take this thinking to its extreme, you can ask much more impactful spending questions.

For example, I have a friend who lives in Miami and only takes Uber XLs (not Uber X) everywhere he goes. He does this even when traveling alone. I was a bit puzzled by this initially, but then he explained. Uber XLs are typically bigger, safer cars than Uber Xs, which means that you are far less likely to get hurt or die in a car accident. Assuming that my friend takes ~6 Ubers a week and pays an additional $10 for each XL, that means he is paying roughly $3,120 per year [6 * 52 weeks * $10] to lower his chance of getting seriously injured in a car crash.

I’m not saying that you need to think about spending your money in this way, but my friend has a point. Every day you make possible life-changing decisions with your money without even realizing it. It could be the car you drive, the food you eat, or where you choose to live. These decisions (which all involve money) will have a bigger impact on the non-financial aspects of your life than you might initially imagine.

In the end, “Your Money or Your Life” isn’t just a question, it’s a reminder of the financial choices we make every day and the profound impact those choices can have on our lives. So, as you consider your next financial decision, remember that there’s more than just money at stake.

Happy New Year and thank you for reading!

If you liked this post, consider signing up for my newsletter.

This is post 379. Any code I have related to this post can be found here with the same numbering: https://github.com/nmaggiulli/of-dollars-and-data