Which asset bubble was the greatest in history? Was it the flower that once sold for the price of a house? Or the magic internet money that went up 10x in a little over a year? Or was it something else entirely?

This debate has raged on for far too long, so I decided to analyze the data and answer this question once and for all. After doing some research (this article helped a lot) and running a few Twitter polls, I have finalized the list of seven asset bubbles that should qualify as contenders for the greatest ever:

- Tulip mania (1637)

- South Sea (1720)

- The Great Crash (1929)

- Japan (1989)

- DotCom (2000)

- U.S. Housing (2007)

- Bitcoin (2021)

Let’s get started.

What Makes a “Great” Bubble?

Before we can select the greatest asset bubble of all time, we need to have some criteria over which to judge a bubble. Therefore, I propose that an asset bubble be evaluated on the following three measures:

- Market Capitalization: The size of the overall market for the asset class

- Price: The size of the price changes of the underlying asset class

- Recovery Time: The amount of time it took for the asset class to reach its prior highs (if ever)

Why do I propose these 3 values as a benchmark for comparison? Because they are useful for comparing bubbles to one another.

For example, let’s say that there is an asset that goes up in price by 100x in a year to reach a total market capitalization of $10 million before collapsing and never recovering. While this asset bubble scored high on price movement and recovery time, it scored low on market capitalization relative to other bubbles, so would likely not be considered the greatest ever.

Of course this process is as much art as science, but I will be fair in my judgement of each bubble. The one thing I can say with near certainty is that the greatest bubble in history will score highly on all three measures. It will be a large market with extreme price changes that does not recover in a reasonable time frame.

With that being said, I am now going to go through each one of these criteria and narrow down the bubble list until we have a winner.

The Too Small Bubbles

Tulip mania (1637)

If we had to choose the greatest bubble in history based on how speculative it was, the Tulip mania of 1637 takes the cake. No bubble in history has had an object of such low utility (a flower) sell for such a high price.

The problem with the tulip bubble is that it wasn’t that large. Despite its prominence in financial pop culture, most of the common knowledge surrounding tulip mania has been grossly exaggerated. As Anne Goldgar, the author of Tulipmania: Money, Honor, and Knowledge in the Dutch Age, states in this article:

Prices could be high, but mostly they weren’t. Although it’s true that the most expensive tulips of all cost around 5,000 guilders (the price of a well-appointed house), I was able to identify only 37 people who spent more than 300 guilders on bulbs, around the yearly wage of a master craftsman.

Jason Zweig also wrote an article on Tulip mania saying:

At its peak, the market for rare tulips seems to have been limited to a few hundred people in total, many of whom traded only once or twice.

Given this information, it appears that Tulip mania was more bark than bite and should not be considered the greatest bubble ever.

South Sea (1720)

Despite suckering in the great Sir Isaac Newton with price increases of 10x in a year, the South Sea bubble wasn’t really a bubble, but more of a scheme. If you read into the complexities of what it was trying to accomplish, it was more like an insane IPO than a traditionally traded asset class.

Regardless of this, my main issue with the South Sea bubble/scheme was that it wasn’t particularly large and there was little evidence of widespread economic impact. As Edward Chancellor stated in Devil Take the Hindmost:

Although the South Sea stock fell to 15 percent of its peak (and the Bank of England and East India shares fell by near two-thirds),the number of mercantile bankruptcies in 1721 did not increase significantly from the previous year and the economy recovered quickly.

So though the bubble was a crazy one for a host of reasons, the negative effects were limited to South Sea shareholders. Thank you, next.

Bitcoin (2021)

While Bitcoin went up 10x from early 2020 into 2021 and then lost 75% of its value in 2022, what happens to it in 2023 and beyond will ultimately determine how we interpret the 2021 “bubble.”

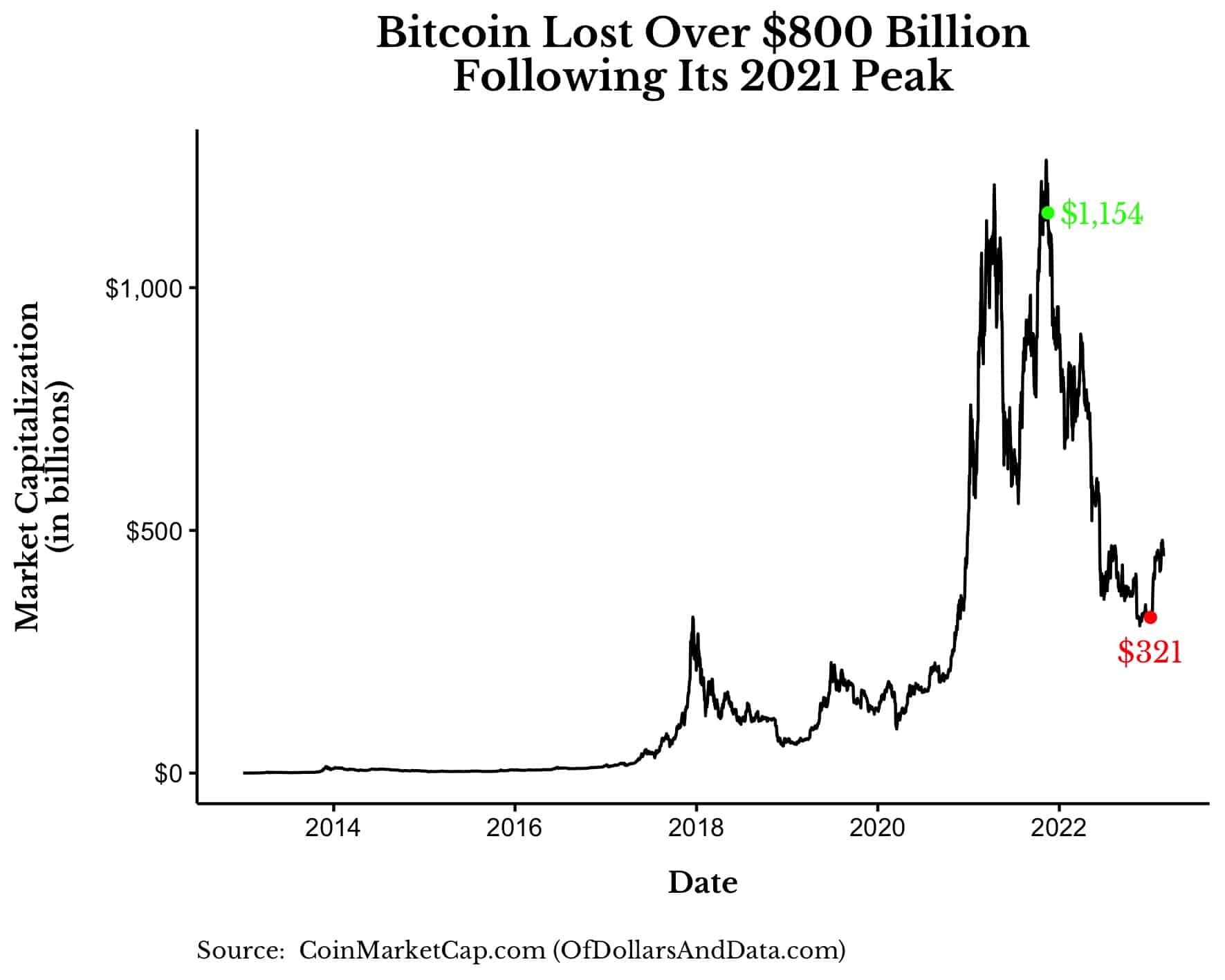

That aside, my primary issue with calling Bitcoin the greatest bubble in history is that Bitcoin’s market cap is too small. At its peak in November 2021, Bitcoin was only worth a little over $1 trillion. As a result, it had only lost a little over $800 billion when it hits its local bottom earlier this year:

Compare this with U.S. stocks (~$30 trillion) and you will see that though Bitcoin gets 50% of the attention on Finance Twitter (FinTwit), it’s too small to play in the bubble big leagues.

The “Stable” Price Bubble

U.S. Housing (2007)

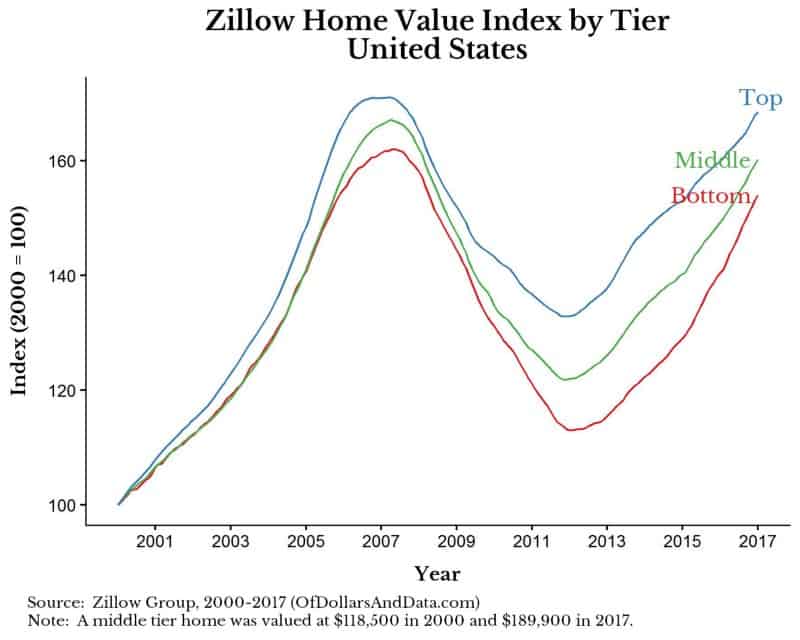

When it comes to BIG bubbles, the U.S. housing bubble of 2007 is the biggest on our list in terms of size. If you look at this visualization provided by Zillow, you will see that the U.S. residential housing market declined in value from $29.2 trillion at its peak to $22.7 trillion when it hit bottom in 2012. That is a decline of $6.5 trillion in the span of half a decade.

My issue with the U.S. housing bubble is that the price changes that went into the bubble were far too “stable” compared to the other bubbles on our list. This chart shows how the median U.S. house price increased ~70% from 2000 to 2007 or an annual gain of 7.9% a year:

Yes, a subset of U.S. real estate markets showed more extreme behavior than this, but the aggregate price changes (<2x) don’t compare to the other bubbles on our list. Additionally, U.S. housing prices recovered within a decade of their old highs. So, while I cannot deny the U.S. housing bubble as being the biggest on our list, due to its lackluster showing in other criteria, it is not the greatest of all time.

The Quicker Recovery Bubbles

The Great Crash (1929)

The Wall Street Crash of 1929 (“The Great Crash”) had both a large change in market capitalization and an extreme run-up in prices in the decade prior. From 1920 to the peak in September 1929, U.S. stock prices increased 6.7x (adjusted for dividends and inflation). In addition, in August 1929 the NYSE estimated that the market value of the 846 listed companies was $90 billion (see Table 1 in this paper).

If we adjust this figure for inflation that would represent less than $1.5 trillion today. So the 90% decline in stocks from 1929 to the summer of 1932 represents an aggregate loss of slightly over $1 trillion.

The only issue I take with the Great Crash is that it recovered back to its September 1929 high within seven years (adjusted for dividends and inflation). Yes, that seven years was difficult for the American people, but it wasn’t necessarily the fault of the stock market crash, but of other systemic issues in the economy.

As Morgan Housel recently noted about the Great Crash:

Only 2.5% of Americans owned stocks in 1929.

The huge majority of Americans watched in amazement as the market collapsed, and perhaps lost a sense of hope that they, too, might someday cash in on Wall Street. But that was all they lost: a dream. They did not lose any money because they had no money invested.

The real pain came nearly two years later, when the banks started to fail.

For these reasons, the Great Crash is a close contender, but not the greatest bubble in history.

DotCom (2000)

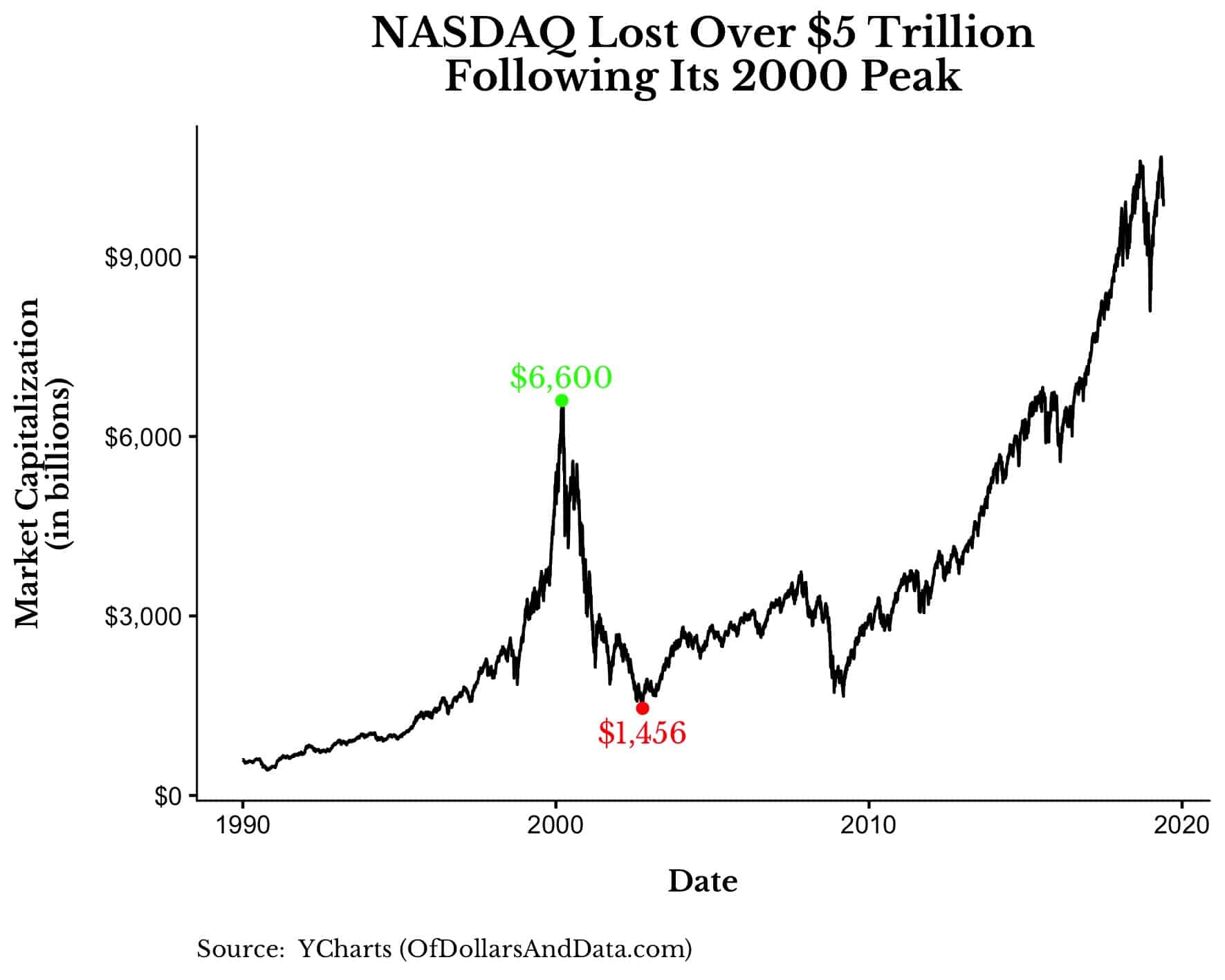

After a 10x increase in prices starting in 1990, the NASDAQ peaked in March 2000 with a market capitalization of $6.6 trillion. The ensuing collapse wiped out $5.1 trillion in market value from the NASDAQ that it wouldn’t gain back for 13 years:

Though I originally thought that DotCom was the greatest asset bubble of all time, something Marc Andreessen said in his interview with Barry Ritholtz (see 17:32) changed my opinion:

The DotCom Crash hit in 2000 and all these ideas that were viewed as genius in 1998 were viewed as complete lunacy and idiocy in 2000. Pets.com being the classic example. So, it’s actually really striking. All of those ideas are working today. I cannot think of a single idea that isn’t working today. The kicker for the Pets.com story is that there is a company Chewy that just got bought for $3 billion.

My issue with calling the DotCom bubble the greatest is as Andreessen suggests: The bubble wasn’t wrong, it was just too early.

The Greatest Bubble of All Time

Japan (1989)

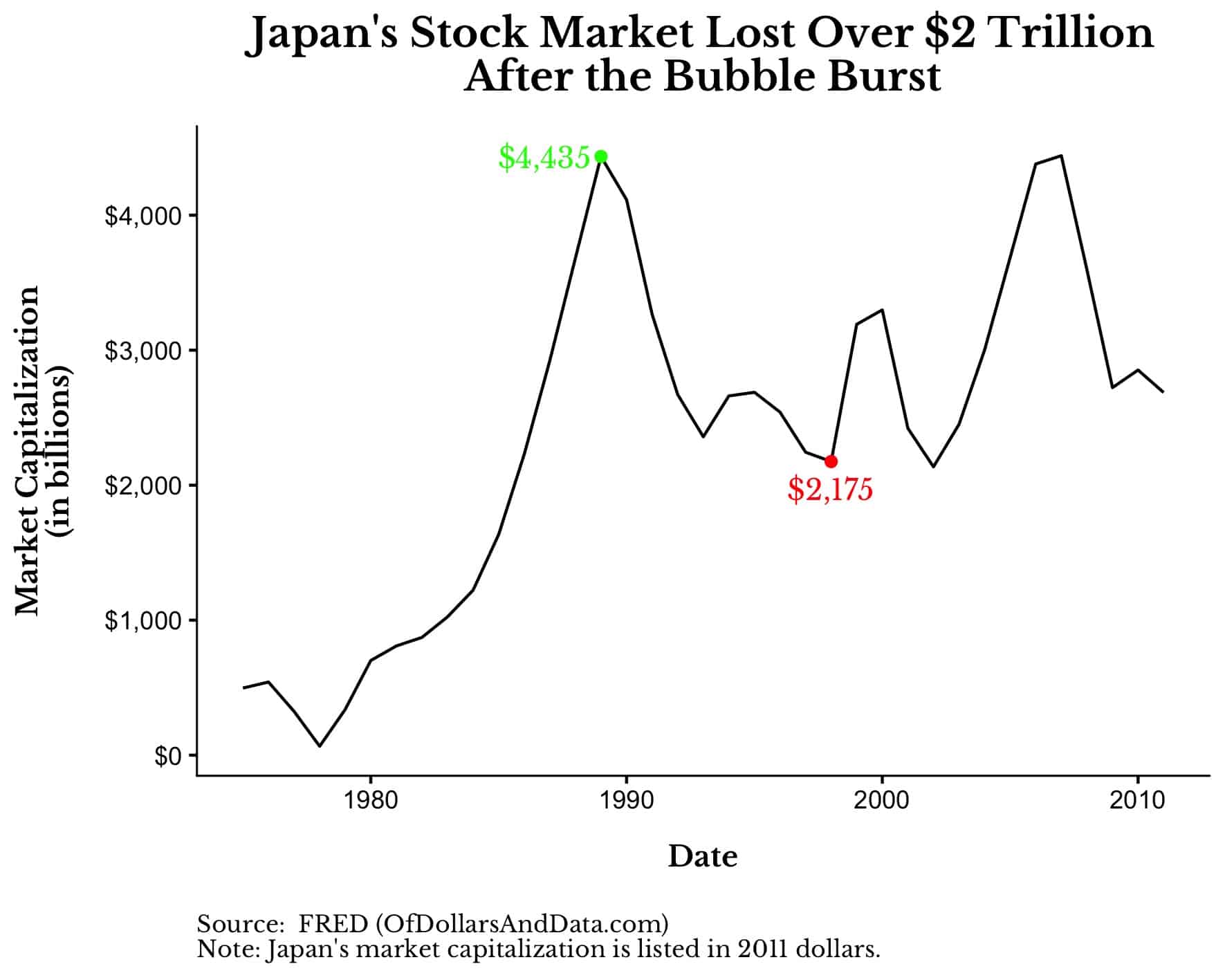

Japan in the late 1980s was the grandaddy of them all. At the peak, the Japanese imperial palace was considered to be worth more than all the real estate in California and the Japanese stock market had grown 10x over the prior decade.

More importantly, in the 33 years since the peak, both Japanese stocks and residential real estate have yet to recover.

To be precise, the Japanese stock market lost over $2 trillion and Japanese land values have declined by $8 trillion since the late 1980s/early 1990s:

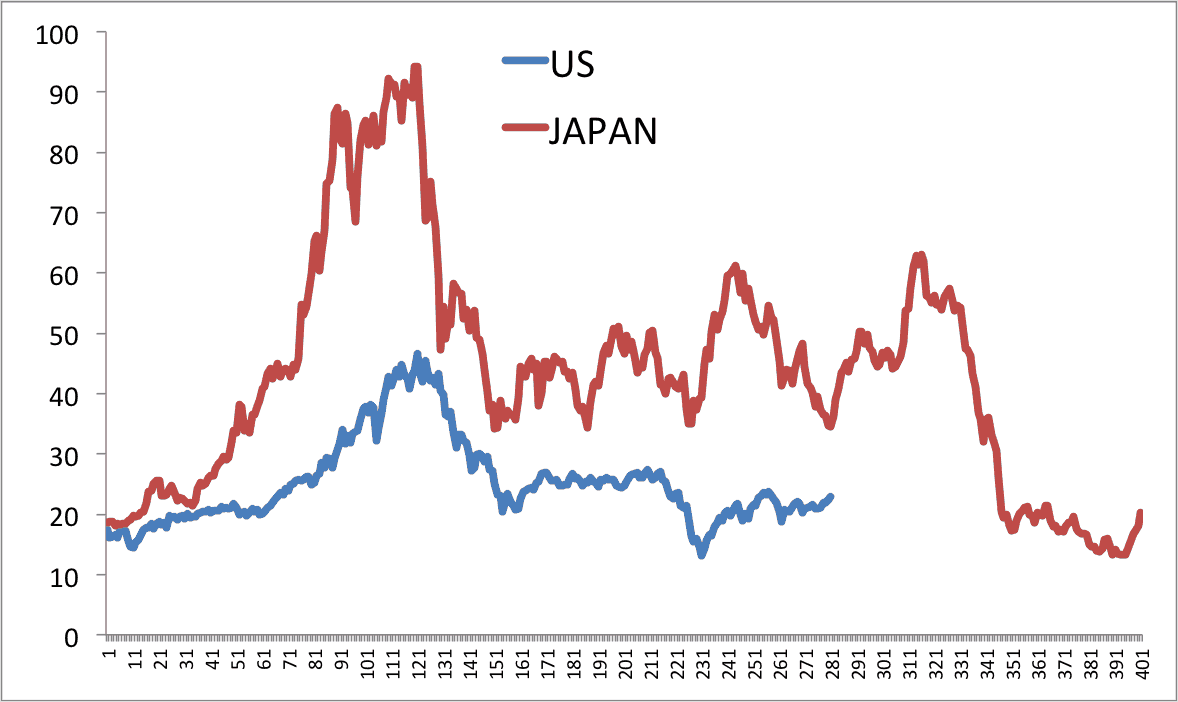

In addition, Meb Faber put together an incredible chart illustrating just how extreme the Japanese bubble was compared to the DotCom bubble on valuation terms (i.e. 10-year P/E ratios):

If you still aren’t convinced, consider reading this post by my colleague Ben Carlson where he makes the case for Japan as the greatest asset bubble ever in much more detail.

Summary

Japan is the winner for the greatest asset bubble of all time because of how well it scores on the three criteria (Market Cap, Price, and Recovery Time) relative to all other bubbles in market history.

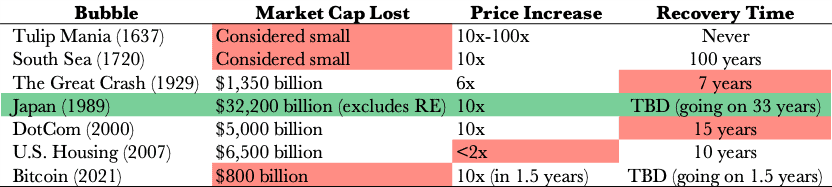

To illustrate this, I have created a table below that summarizes how each of the seven bubbles fared on these three measures.

I also added red boxes for each bubble to highlight what I consider the weak points in the discussion for greatest of all time (i.e. too small, little price movement, or decent recovery time). Japan is the only bubble in all green because of how well it scores on the three criteria:

Note: The market capitalization lost in the Japanese bubble listed above excludes the $8 trillion of estimated losses in land/real estate (“RE”) since the early 1990s. I did this to make the comparison with the other bubbles (i.e. one asset class only) more meaningful.

This table illustrates that though other bubbles are close contenders, Japan remains in a league of its own as the greatest asset bubble in history.

The Bottom Line (The Madness of the Crowd)

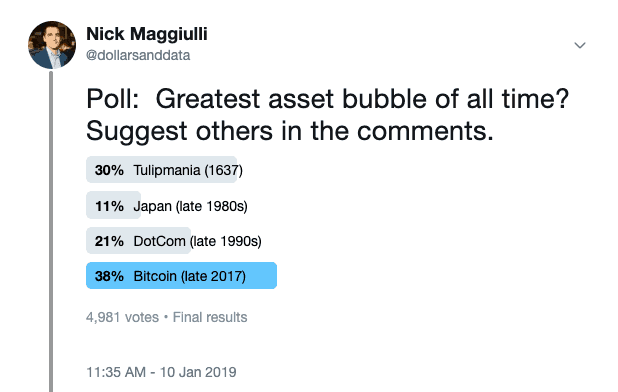

If there is anything that we can learn from the many bubbles of history, it is that the crowd is not always right. When I asked Twitter what was the greatest asset bubble of all time back in January 2019 (where I used the first Bitcoin bubble from 2017), here was the result:

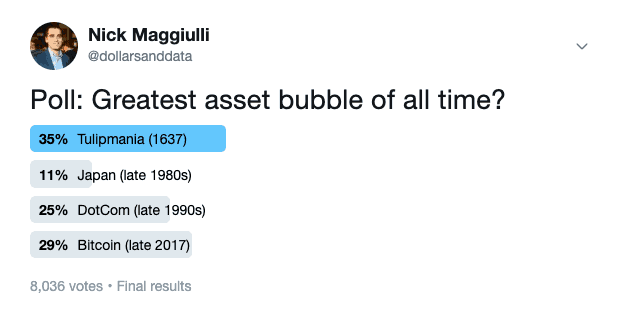

Note that at this point in time Bitcoin was near its lowest point since its December 2017 peak. To correct for this recency bias, I re-asked the same question in late May 2019 after Bitcoin’s price had recovered a bit:

Besides the additional few thousand votes, you will notice that the mood around Bitcoin shifted with its recent price recovery, leaving Tulip mania as the winner. This is why listing Bitcoin as a bubble in 2021 can be problematic. It is the bubble that keeps on recovering.

The other thing to notice from these polls is that the two greatest bubbles in history (Japan and DotCom) also contain the least number of votes. Maybe I should be using a different set of criteria for assessing bubbles, but I will let you be the judge of that.

The only thing I can say with certainty is that bubbles will occur in the future. I don’t know when. I don’t know where. But I know they will happen.

So, what should you do when asset bubbles inevitably appear?

Don’t participate.

Ignore them.

Look the other way.

That is your only hope.

But, you don’t have to believe me though. Consider the words found on an anonymous pamphlet from the South Sea Bubble of 1720:

The additional rise of this stock above the true capital will be only imaginary; one added to one, by any rules of vulgar arithmetic, will never make three and a half; consequently, all the fictitious value must be a loss to some persons or the other, first or last. The only way to prevent it to oneself must be to sell out betimes, and so let the Devil take the hindmost.

Few lines in a book have ever given me the chills, but this was one of them. For that reason, I highly recommend Devil Take the Hindmost if you want to learn more about asset bubbles and market history.

Happy investing and thank you for reading!

If you liked this post, consider signing up for my newsletter.

This is post 129. Any code I have related to this post can be found here with the same numbering: https://github.com/nmaggiulli/of-dollars-and-data