As the saying goes, “Risk happens fast.” From medical emergencies to job loss to car and home repairs, unforeseen events can quickly derail your finances—especially if you’re not prepared. That’s where an emergency fund comes in.

An emergency fund is a financial safety net designed to help you weather life’s storms with ease. While most financial experts emphasize the importance of having an emergency fund, the question of how much you should save for emergencies is still up for debate.

In this blog post, I’ll dig into the data on emergency funds and provide you with a framework for thinking about how much to save in your emergency fund and how to build an emergency fund efficiently. To begin, let’s look at some common myths surrounding saving for emergencies before we tackle how much you should save in your emergency fund.

How Much To Save In Your Emergency Fund: Debunking Common Myths

A common question among those planning their financial future is how much money should be set aside in an emergency fund. But before we can answer this, let’s debunk some common myths surrounding emergency funds by examining typical emergency expenses, the kinds of emergency expenses that lead to bankruptcy, and how much people usually save in their emergency funds.

How Much is the Typical Emergency Expense?

You’ve probably heard that only one in three Americans could comfortably cover a $400 emergency expense. Not only is this a somewhat misleading statistic, but $400 is not nearly enough to cover the typical emergency expense among U.S. adults. In August 2022, LendingClub released a report which found that the average emergency expense was $1,400 and that “middle-aged and high-income consumers” were more likely to have emergency expenses.

Why did these kinds of consumers have more emergency expenses than everyone else? Because they own more possessions that generate such expenses. We can see this clearly if we look at the most common kinds of emergency expenses that individuals face. As the LendingClub report found:

At 30%, car repairs are the most common unexpected expense, and consumers paid an average of $1,008. The next-most common expenses are health-related, with 21% of consumers facing at least one health-related emergency expense and spending an average of $1,361. Housing- and relocation-related expenses had the highest average cost at $2,042, and 19% of consumers faced this type of expense.

But LendingClub’s data may be somewhat conservative when it comes to the size of emergency expenses.

Bankrate did an analysis in January 2020 which found that the median emergency expense was $1,750 with the average being closer to $3,500 among U.S. adults. I can’t tell which data source is more accurate, but if we adjust for inflation, the typical emergency expense is likely around $2,000 today. This illustrates that the $400 figure often cited by the media vastly underestimates the cost of a typical emergency expense in the U.S.

However, we don’t just care about the size of the typical emergency expense, but what kind of expenses lead to financial ruin as well. For this we turn to the next section.

What Kind of Emergency Expenses Lead to Bankruptcy?

It is often reported that medical bills are the most common cause of personal bankruptcy in the United States. In fact, according to a report from the American Journal of Public Health, “66.5% of bankruptcies were tied to medical issues.”

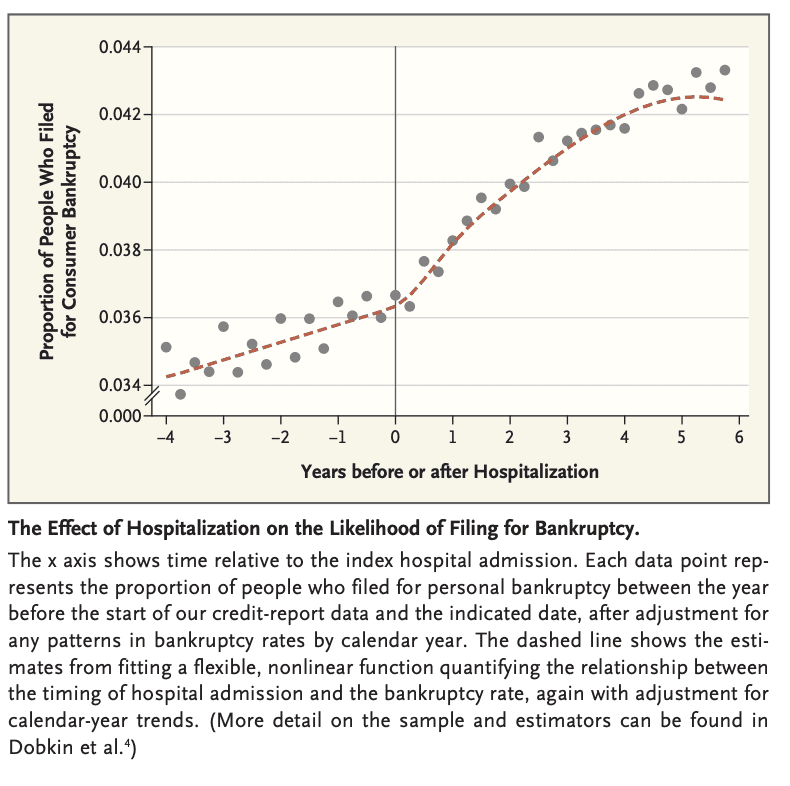

However, this seems to be a case of correlation and not causation. Researchers at the Massachusetts Medical Society examined medical events and future bankruptcies and found that only 4%-6% of bankruptcies are caused by hospitalizations and medical debt. They discovered this by looking at the proportion of bankruptcies that occurred before and after major hospitalizations:

As you can see, the proportion of people who file for bankruptcy in the years following a hospitalization rises, but not by much. So why the media gets this wrong? Because they assume that if many people who file for bankruptcy have medical debt, then it is the medical debt that caused their bankruptcies. Unfortunately, they overlook the fact that there are far more people with medical debt that do not declare bankruptcy.

Medical debt, by itself, doesn’t seem to be the cause of most bankruptcies. So what is? This paper, which examined household spending patterns and personal bankruptcies among Delaware households in 2003, suggests that the answer is—overconsumption. As the paper states:

A closer look at the bankrupt households reveals that they consume in a surprisingly similar fashion to the control groups…[however] the bankrupt households make less than one half of what the control households do.

Though the bankruptcy households had roughly similar levels of mortgage, automobile, and credit card debt as the non-bankrupt households, their incomes were much lower. They were keeping up with the Joneses, and it cost them in the long run.

This gets at a bigger point about what kinds of households get into financial trouble. The answer is—it’s generally the same ones over and over again. As this article on financial distress found:

While many U.S. consumers (35%) experience financial distress as defined by severe (120 days past due) delinquency at some point in the life cycle, most financial distress events are primarily accounted for by a much smaller proportion of consumers in persistent trouble—less than 10% of borrowers account for half of all distress.

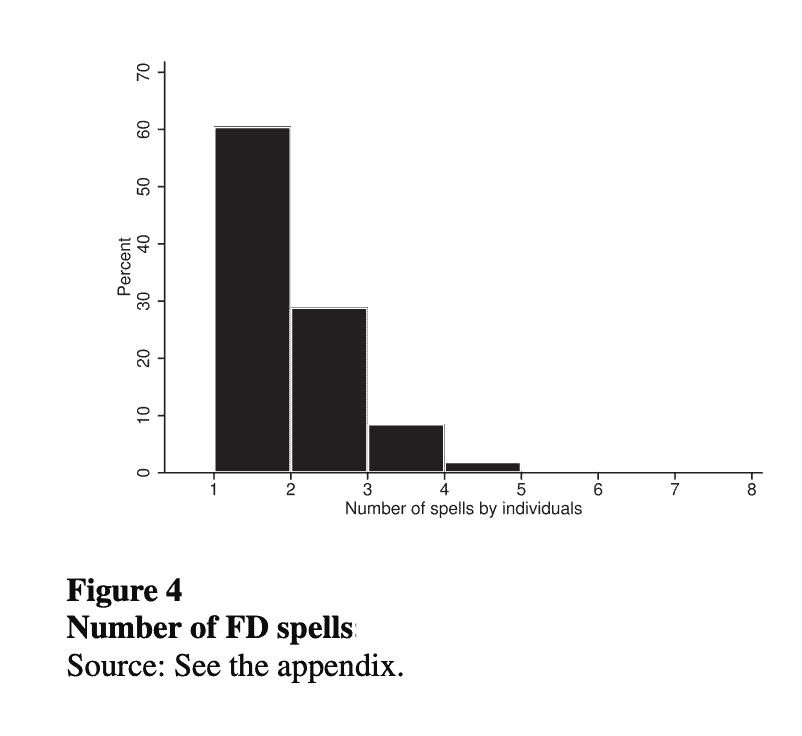

A small number of people are experiencing most of the financial hardship. You can see this clearly when you look at the percentage of people with a certain number of financial distress (FD) spells over time:

Most individuals (60%) that experience financial distress experience it once and then never again. However, there is a small minority (~10%) of people that experience 3 (or more) distinct financial distress events in their lifetimes.

Now that we have looked at what kinds of emergency expenses lead to bankruptcy and how overconsumption seems to be the biggest contributor to this, let’s examine how much people tend to save for emergencies.

How Much Do People Typically Save in Their Emergency Fund?

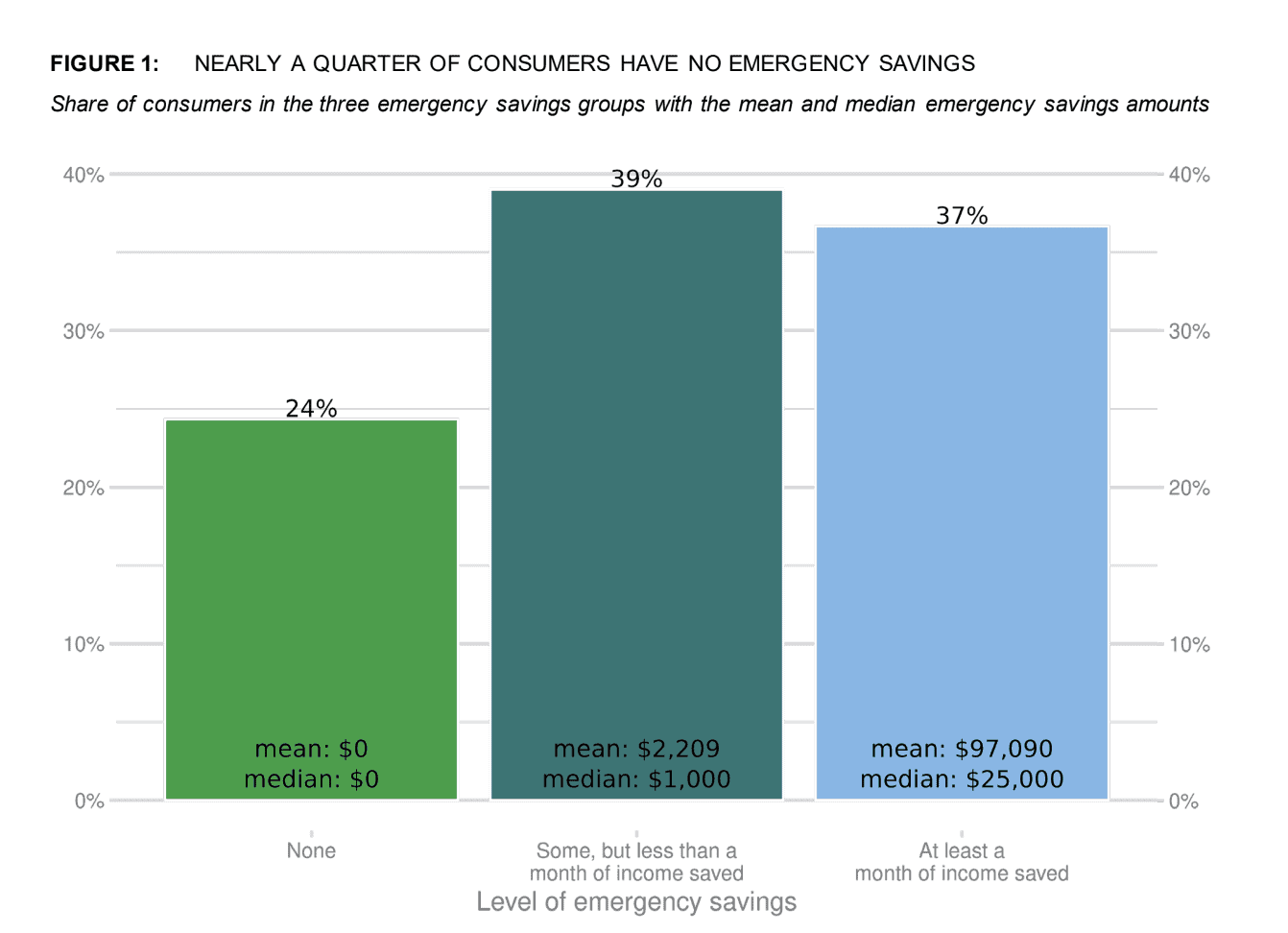

When it comes to saving for emergencies, the typical American doesn’t save all that much. As this March 2022 report from the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau demonstrated, 24% of consumers have no emergency savings, 39% have less than a month of income saved, and 37% have a month (or more) of income saved for an emergency:

This data suggests that approximately 44% of consumers have less than $1,000 saved in an emergency fund. Given that the typical emergency expense is around $2,000 (based on the prior section), you can see why this is problematic.

More importantly, this data suggests that there is a huge variance in emergency savings at the high end. While the median amount of savings is $25,000 (for those with at least a month of income saved), the average is nearly $100k. This means that there are some people who have in excess of six figures saved for a rainy day. Though the typical emergency expense is only a few thousand dollars, these ultra-high savers are also likely higher spenders that are worried about months of lost income at a time.

Now that we have debunked some common myths surrounding emergency funds, let’s take a look at the factors you should consider when saving for your own emergency fund.

How Much Should You Save in Your Emergency Fund?

Though the typical emergency expense for most households is only a few thousand dollars (as shown above), large financial emergencies (such as job loss) could warrant that you save a much larger amount. For this reason, the biggest factors to consider when saving for an emergency fund are:

- Monthly expenses: The most important factor when determining how much to save in an emergency fund is your monthly spending. Knowing how much you spend on housing, groceries, transportation, and other essential costs will be necessary when determining how much to set aside for an emergency. Many financial experts recommend saving 3-6 months of expenses, but you may want to save more depending on the other factors listed below.

- I’ve had 6 months of expenses saved since around age 25, but have never come anywhere close to exhausting them. Let’s hope it stays that way.

- Income stability: If you have a stable job or a predictable income, you may need a smaller emergency fund than someone who is self-employed, a freelancer, or has irregular income. For those that have to regularly deal with fluctuations in income, saving more for an emergency can be a financial lifesaver.

- Family situation: If you are single in your 20s, you may not need to have as large of an emergency fund as a middle-aged individual with a family. Having dependents or being the breadwinner in your family means that you probably need to have a larger emergency fund.

- Insurance coverage: Consider how healthy you are and the comprehensiveness of your insurance coverage. If you have a history of health issues or subpar insurance coverage, you might want to save a bit more to cover future medical expenses.

- Debt: If you have significant debt, such as student loans, car loans, or credit card debt, it’s important to maintain a more substantial emergency fund to continue making payments in case of job loss or other financial setbacks.

- Risk tolerance: Some people are more comfortable with risk than others. If you have a low risk tolerance, you may want to save more in your emergency fund to feel secure. On the other hand, if you’re comfortable with taking more risks, you might opt for a smaller emergency fund.

Given all this information, you can see why there is no one-size-fits all emergency fund recommendation. What works for one person may fail for another. This is why the right emergency fund is the one that allows you to sleep at night. If that means 3 months of expenses or 2 years of expenses, then so be it.

Whatever you decide to do, you should also keep in mind that your finances are more dynamic than you realize. For example, if you saved up 6 months of your current expenses, you may be able to make this last a bit longer if you cut out your discretionary spending (i.e. entertainment, eating out, etc.). In addition, if you lose your job, you may be able to find a new one more quickly than you realize.

Of course, you can’t know what the future will hold, but by thinking critically about your emergency fund and planning responsibly you lower your chances of financial ruin due to an emergency.

Now that we have discussed how much you should save in your emergency fund, let’s look at the best way to build an emergency fund.

How to Build Your Emergency Fund (and Where to Keep It)

When it comes to saving for an emergency, below are a few tips you can use to build one efficiently:

- Set savings goals: Given the unpredictability of life, my general approach to saving money is to “save what you can.” However, when it comes to saving for an emergency fund, we have to be more diligent in our approach. This is why I recommend setting savings goals to track how you are spending your money until your emergency fund is built up. Once that is done, then you don’t have to be as strict with specific goals and monthly tracking.

- Automate as much as you can: The best way to set savings goals is to automate your savings as much as possible. Setting aside money from your paycheck and “paying yourself first” is the best way to do this, especially if you might be tempted to spend any money that isn’t normally set aside.

- Cut expenses mercilessly: While I am generally not a fan of cutting expenses, when it comes to saving up for an emergency fund, this is the way to go. The only time we should cut our expenses is in an emergency, and not having any emergency saving is an emergency. As a result, you should try to cut back as much as possible until you’ve built up some financial cushion. Only then can you ease off the expense cutting and focus on growing your income to build your long-term wealth.

Once you start following the steps above, you still might be wondering: Where should I keep this extra money I save? Should I hold it in cash or put it somewhere else?

Generally, you want your emergency fund to be as low risk and as liquid as possible. For many this might mean keeping it in a checking or saving account. Unfortunately, most checking and savings accounts aren’t paying that much today and haven’t paid much for the last decade. However, with short-term Treasury rates above 5%, there are some better options to consider:

- Money market accounts: Money market accounts are FDIC-insured accounts that pay a yield on your cash holdings. And with interest rates where they are today, many money market accounts are paying 4% (and up) on deposits. While this yield is attractive, there are typically restrictions one how often you can withdraw money from these accounts. But, since you are using these accounts for emergencies only, these withdrawal restrictions shouldn’t be a problem.

- Money market funds: Unlike money market accounts, money market funds are not FDIC-insured and must be accessed through a brokerage firm. These funds tend to invest in short-term debt securities (like U.S. Treasury bills) and, therefore, can provide a higher yield to investors than those with money market accounts. And while there are no limits on withdrawals, the value of your emergency fund will fluctuate if interest rates change in the future. This is something to keep in mind before investing in a money market fund.

- Side note: While money market funds aren’t FDIC-insured, they have generally been very safe. There’s only been one instance in history where one of these funds “broke the buck” and wasn’t able to offer 100% of its invested funds back to investors. Unfortunately, that fund had invested a portion of its assets into commercial paper at Lehman Brothers.

- Treasury bills: If you want to go straight to the source, you can invest your emergency fund directly into U.S. Treasury bills as well. While these will provide the highest yield of the options above, you also face interest rate risk just like you would with money market funds. Those that had their emergency funds invested in Treasury bills at the beginning of 2022 learned this the hard way when rates increased dramatically throughout the year and sent bond values plummeting. While short-term Treasury bills are less sensitive to interest rates than longer duration bonds, their values can still have fluctuate to some extent. If this bothers you, then you may want to put your emergency funds elsewhere.

Now that we have examined how to build an emergency fund effectively and where to put your emergency funds, let’s wrap things up by discussing why it all matters.

The Bottom Line

In conclusion, having an emergency fund is crucial for weathering life’s unexpected events and maintaining financial stability. By debunking common myths surrounding emergency funds and understanding the typical emergency expenses people face, you can better determine how much you should save and tailor your emergency fund to your unique financial situation.

It’s important to keep perspective when considering your financial preparedness. While striving for a robust emergency fund is commendable, don’t let it cause unnecessary anxiety. With 24% of people in the U.S. having nothing saved and another 39% having less than one month’s income saved for emergencies, you may already be in a stronger financial position than you realize. This doesn’t mean that you can throw caution to the wind, but it does imply that you are probably trying to over-optimize your finances.

The truth is that no one knows the future and all the preparedness in the world can’t prevent certain outcomes from unfolding. Ultimately, you have to make a well-informed effort and let the chips fall where they may. That’s all we can ever do. Thank you for reading.

If you liked this post, consider signing up for my newsletter.

This is post 346. Any code I have related to this post can be found here with the same numbering: https://github.com/nmaggiulli/of-dollars-and-data