The best decision I ever made in my life was a complete fluke. It happened during the beginning of my senior year in high school. I was compiling the list of which colleges to apply to when my godfather asked me whether I was applying to Stanford. To be honest, I didn’t know much about Stanford at the time other than they were a private school. And private schools were definitely off the list.

You see, neither of my parents graduated from college so I didn’t grow up knowing anything about college or what options were available to me. So when I started looking at where to apply I focused on the one thing that I did understand—cost. As a result, I was only looking to apply to public colleges in California, mostly the University of California (UC) schools. Public because it was cheaper and California so I could keep the CalGrant money (~$10,000 a year).

After explaining this to my godfather he insisted that I apply to Stanford because he knew they would provide some sort of financial aid package. I agreed and started doing research online before applying. Unfortunately, I quickly realized that getting into the school was easier said than done.

After scrolling the College Confidential online forum for hours I realized I was in over my head. One student who got accepted had discovered their own asteroid, another was a stuntman, and another founded a $1M charity. How was I supposed to compete with these kids?

I didn’t think I had any real chance, but I did learn that Stanford had a single-choice early action (SCEA) program that allowed you to apply early, but you could only apply early to them and no other school. Because I felt so unsure about my chances of getting in, I convinced myself that I would apply early just to get it over with. By mid December I would know if I was in or not.

Unfortunately, I only had nine days until the early application deadline. So I scrambled through the numerous essays and short responses to put my application together and sent it in on the day it was due.

Unbeknownst to me, I had just made the single best decision of my life. However, I didn’t realize this until a few weeks after I had applied. Because in those weeks after applying I kept scouring the College Confidential forums and learned something huge.

In the year prior (2007), the overall acceptance rate into Stanford was a sobering 10.3%. However, the acceptance rate for those who applied early was closer to 20%. Through sheer dumb luck I had doubled my chances of getting into one of the most selective schools in the country.

And guess what? It worked. Out of the 20,747 applicants who applied during the regular admissions process in 2008, Stanford accepted 8%. However, of the 4,551 students who applied early, they accepted 16%! I happened to be one of them.

As I think back upon it now, applying early should be the obvious choice for almost anyone. After all, what other single decision can double your chances of getting into such a selective school? I know of none.

This is why one of the most important things I have ever learned is to respect the base rate.

The base rate is simply the probability of some event occurring when you have no other information. In this case, the base rate of getting accepted as regular applicant was 8%, while the base rate for getting accepted as an early applicant was 16%. Without any other information, you should assume that you will experience the base rate.

Unfortunately, many of the users on the College Confidential forum didn’t follow this logic. They generally recommended against applying early because they believed that the early applicant pool was stronger than the regular applicant pool. I have no idea whether this was true, but, then again, neither did they. They had no empirical evidence to go on, just anecdotes.

Therefore, since they had no real information to go on, the best thing to do was use the base rate. Assume you will have the same outcome as the average person in the same situation. This is why applying to college early was such a good decision for me though I didn’t know it at the time. The base rate was two times higher!

You can utilize base rates to make all kinds of better life decisions as well.

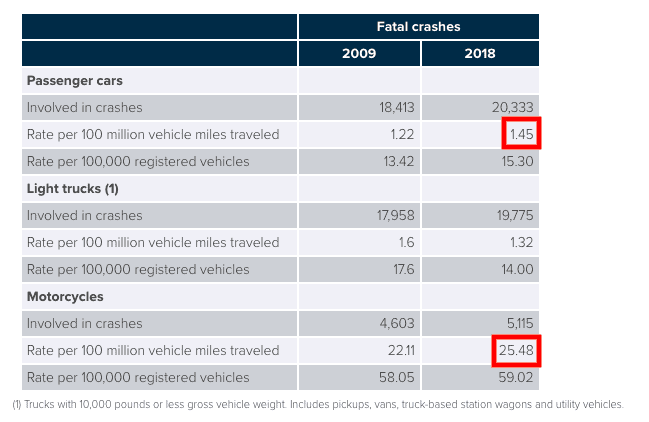

For example, base rates are the reason why I won’t ever regularly drive a motorcycle. As the table below illustrates, the 2018 fatality rate for those using motorcycles is roughly 18 times higher than those in passenger cars when controlling for the number of miles driven:

Driving can be risky enough as it is, but doing it on a motorcycle is playing with fire.

You can also use base rates to better assess future career opportunities too. For example, if you know you want to make a lot of money very early in your career, then getting into investment banking or private equity is probably the way to go. Why? Most people going into those industries make lots of money early in their career.

The reason why base rates are so useful is that they allow you to imagine an outcome without actually doing it. You get to use the experience of others and then apply it to your decision-making.

However, there are certain circumstances where following the base rate is a bad idea.

When Do Base Rates Fail?

Base rates are incredibly useful in scenarios where you have little information. However, once you have some information, they can lose their relevance.

For example, if you told me that you wanted to play in the NBA, I would tell you to consider a different career path because the base rate of making it in is so low. However, if you then revealed to me that you were seven feet tall, that changes things a bit. The base rate no longer applies because I have new information showing that you are different than the average person.

And this isn’t just a hunch on my part either. If you look at the data, height is one of the best predictors of likelihood of reaching the NBA. As Seth Stephens-Davidowitz wrote in Everybody Lies:

I estimate that each additional inch roughly doubles your odds of making it into the NBA. And this is true throughout the height distribution…It appears that, among men less than six feet tall, only about one in two million reach the NBA. Among those over seven feet tall, I and others have estimated, something like one in five reach the NBA.

So, if you have information that suggests that you are different from the typical person, then you can ignore the base rate.

This is why I can justify blogging despite the low base rate of success. Early on blogging looked like a silly decision because most writers never build any sort of audience. However, as I got positive feedback from readers, I was motivated to keep going. The information changed, so the base rate no longer applied.

When it comes to investing, I try to provide advice that has the highest base rate for long-term success. This is why I recommend buying a diverse set of income-producing assets if you want to build wealth. With no other information about you, it’s the best thing out there.

It’s not that you can’t get rich doing something like day trading, but I know that only about 1 in 20 day traders remain profitable in the long run. Will you be among the select 5% of day traders that are profitable? Probably not. But you may have information that suggests otherwise.

Of course, your information may not be good information either. You could be deluding yourself into thinking you have skill when you actually don’t. So don’t part ways with the base rate unless you have some solid evidence that illustrates you are different.

The optimal approach when it comes to making decisions isn’t to blindly follow the base rate, but to respect it. Because not doing so can get you into lots of trouble.

Happy investing and thank you for reading!

If you liked this post, consider signing up for my newsletter.

This is post 228. Any code I have related to this post can be found here with the same numbering: https://github.com/nmaggiulli/of-dollars-and-data