In 2017 Hendrik Bessembinder released an academic paper that rocked the investment world. His research (full text here) called into question the validity of stock picking by highlighting the large skew in individual stock performance. As the paper’s abstract states (emphasis mine):

Four out of every seven common stocks that have appeared in the CRSP database since 1926 have lifetime buy-and-hold returns less than one-month Treasuries. When stated in terms of lifetime dollar wealth creation, the best-performing four percent of listed companies explain the net gain for the entire U.S. stock market since 1926, as other stocks collectively matched Treasury bills.

If only 4% of stocks can win in the long run, why waste time picking stocks, right? While this conclusion seems sound, it isn’t the right way to think about this paper.

The issue (which has nothing to do with Bessembinder’s logic) is the time frame being used. Yes, over the course of the next 80 years, most companies around today will likely be gone. As Geoffrey West noted in Scale: The Universal Laws of Life, Growth, and Death in Organisms, Cities, and Companies:

Half of all the companies in any given cohort of U.S. publicly traded companies disappear within ten years, and a scant few make it to fifty, let alone a hundred years.

This simple fact is illustrated in that not a single company in the current Dow Jones Industrial Average was in the index 100 years ago (the company that has been in the Dow the longest, Exxon Mobil, was added on October 1, 1928 after the index was expanded from 20 to 30 companies).

My problem is that you and I don’t live in 80-year investment time frames. While Jason Zweig says that he “measures his time horizon in centuries,” most of us don’t.

We feel the impact of stocks on a much shorter time frame (i.e. daily to yearly). Therefore, we should examine skewness over this shorter time frame as well.

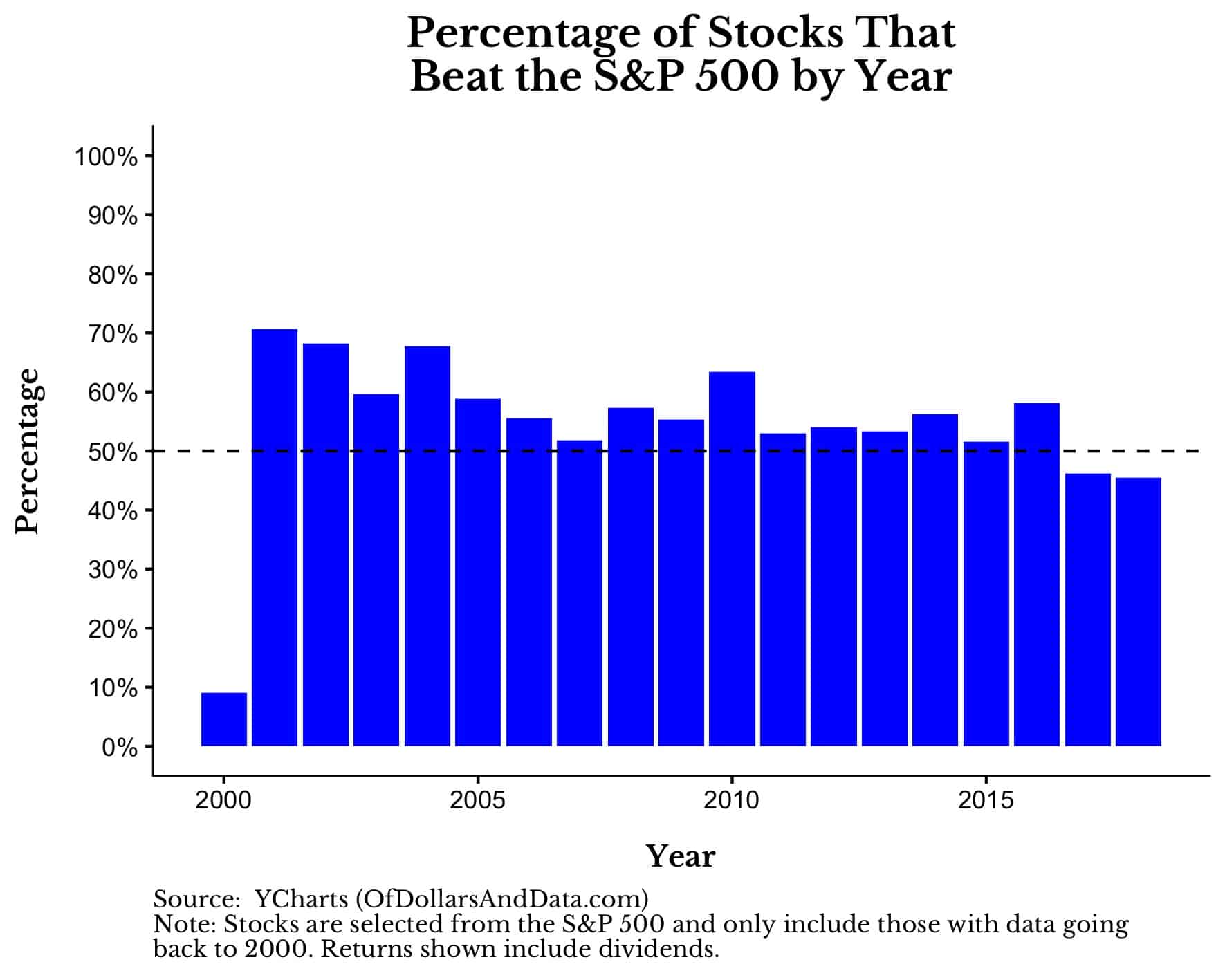

To do this I took all the stocks in the S&P 500 as of today and looked at their performance going back to the year 2000 (this includes 396 companies will full return data). I then compared the performance of these stocks to the performance of the S&P 500 in each year to see what percentage of companies would beat the market.

Note that my list should overstate how often individual stocks beat the market since I am knowingly selecting companies that are in the S&P 500 in 2019 (i.e. winning stocks).

However, even when we select for these future winners, the percentage of stocks that beat the market in a given year is not negligible:

As you can see, only a small percentage of stocks outperformed the market in the year 2000 (thank the DotCom bubble). However, in every year after that, the percentage of stocks that have outperformed the market is sizable.

Yes, as I mentioned before, these numbers will be biased (usually upward) because of my selection sample. However, even in 2018, a year in which we do not have selection issues, 45% of the stocks in the S&P 500 outperformed the index.

This fact could provide motivation for those who might attempt to beat the market over shorter time periods.

But, those attempting to beat the market will have to contend with another issue—the market is always changing. What constitutes the S&P 500 is in flux every single year.

Yes, most of the stocks remain the same, but if you invest in the S&P 500 you have the benefit of a committee that selects which stocks to add/remove over time.

This is why Bessembinder’s paper won’t have much practical value for your typical investor despite how great it is. Because most people don’t buy a set of stocks and hold them for life.

Even indexers are constantly shuffling in and out of stocks over the years whether they realize it or not. And the world’s best investors aren’t immune from change either.

Consider what Charlie Munger, Warren Buffett’s long time business partner, told a Chinese financial publication:

Warren and I hated railroad stocks for ages. But the world changed, and pretty soon we got down to only four big railroads. And technology changed. The whole world changed. Then we bought railroad stocks and then we bought the whole railroad. We changed our minds because the facts changed. Don’t you change your minds when the facts change?

I think stock picking is difficult, but maybe not as difficult as some people make it out to be. However, even if you think you can beat the market over shorter time periods, the reason you still shouldn’t engage in stock picking has nothing to do with return, but with risk.

As this graphic illustrates, it’s the variance (not the return) that changes a lot as you add more stocks to your portfolio:

This is one more reason why the skew in stock returns doesn’t matter all that much for you. Because even if you are a stock picker, you are likely to diversify among a large number of positions and capture that skew.

Timing Matters

I have noticed that more and more of my work is concerned with thinking about time and how it effects investors. Whether you are deciding how to invest over the next century or how to spend your 10,000 minutes over the next week, time is the most important concept in finance.

As it ebbs and flows so do your conclusions. An asset that once was safe is now risky. A strategy that used to be losing can suddenly become a winner. All that was needed was time.

Yet again time is the great arbiter of skewness. What is invisible over days will be made clear in decades and centuries. With that being said, I will leave you with my favorite quote about time in the entire investment literature.

From Brian Portnoy’s Geometry of Wealth:

Finance posits a linear conception of time. A day is a day is a day. One five-year period is precisely the same duration as another five-year period. Episodes of time are uniform and we experience them unidirectionally, from present to future.

Psychology disagrees: The human experience with time is non-linear and lumpy. The duration of those seconds and decades expand and contract.

Time is elastic. It slows down during traumatic accidents and speeds up as we grow older. There’s an old line in the world of parenting that “the days are long but the years are short.”

That’s mind time at play and mind time is what matters in the pursuit of wealth and funded contentment.

Thank you for reading!

If you liked this post, consider signing up for my newsletter.

This is post 139. Any code I have related to this post can be found here with the same numbering: https://github.com/nmaggiulli/of-dollars-and-data