One of the greatest short stories I have ever read is How Much Land Does a Man Need? by Leo Tolstoy. The story centers around a peasant named Pahom who wants to acquire land so that his family can live a more comfortable life.

Unfortunately, Pahom’s quest for comfort quickly becomes an obsession as he amasses more and more land, yet is never fully satisfied.

The climax of the story occurs when Pahom hears of a neighboring tribe who is selling their land for next to nothing. In an effort to secure some of this cheap land, Pahom showers the tribe and its chief with lavish gifts.

The chief becomes so impressed with Pahom’s hospitality that he makes him an irresistible offer. The chief tells Pahom that he can have all the land that he can mark off within a single day as long as he returns to his starting point before the sun sets.

Pahom accepts the chief’s offer with his mind racing over how much land he will soon have in his possession. The next day Pahom takes off in haste as he starts plotting out his newly imagined estate.

However, as the day drags on, Pahom begins to tire and questions whether he can return to his starting point in time. With his body breaking down from a full day of walking, Pahom has no choice but to go into a full sprint as dusk quickly approaches.

Rushing with all his might, Pahom crosses the starting point just as the sun is setting only to collapse from exhaustion and die.

The tale ends with Pahom being buried in a grave just long enough to fit his body, with the final line of the story reading:

Six feet from his head to his heels was all he needed.

I was reminded of this story and its timeless lesson about human nature and greed after reading a recent interview with ex-Goldman CEO and current billionaire Lloyd Blankfein. In the interview, Blankfein claims that, despite his immense wealth, he isn’t rich:

Blankfein insists that he is “well-to-do,” not rich. “I can’t even say ‘rich’,” he insists. “I don’t feel that way. I don’t behave that way.”

He says he has an apartment in Miami as well as New York. But he abjures most of the trappings. “If I bought a Ferrari, I’d be worried about it getting scratched,” he jokes.

“Ken Griffin [the Chicago-based hedge fund billionaire] buys all these houses. He’s out there every minute, calling the office. It can’t make any sense to people outside.”

As shocking as this sounds, I kind of understand his sentiment. When you regulary hang out with people like Jeff Bezos and David Geffen and count Ray Dalio and Ken Griffen among your peers, having only $1 billion doesn’t seem like much.

However, on a completely objective basis, Blankfein is in the top 0.01% of U.S. households, or the 1% of the 1%. According to Saez and Zucman, the top 0.01% of U.S. households (~16,000 families) had a net worth of at least $111 million in 2012. Even if you adjust for the increase in asset prices since 2012, Blankfein would easily be in the top 0.01%.

But it’s not just Blankfein with this perception problem. Most people at the upper end of the income spectrum think they are less wealthy than they actually are.

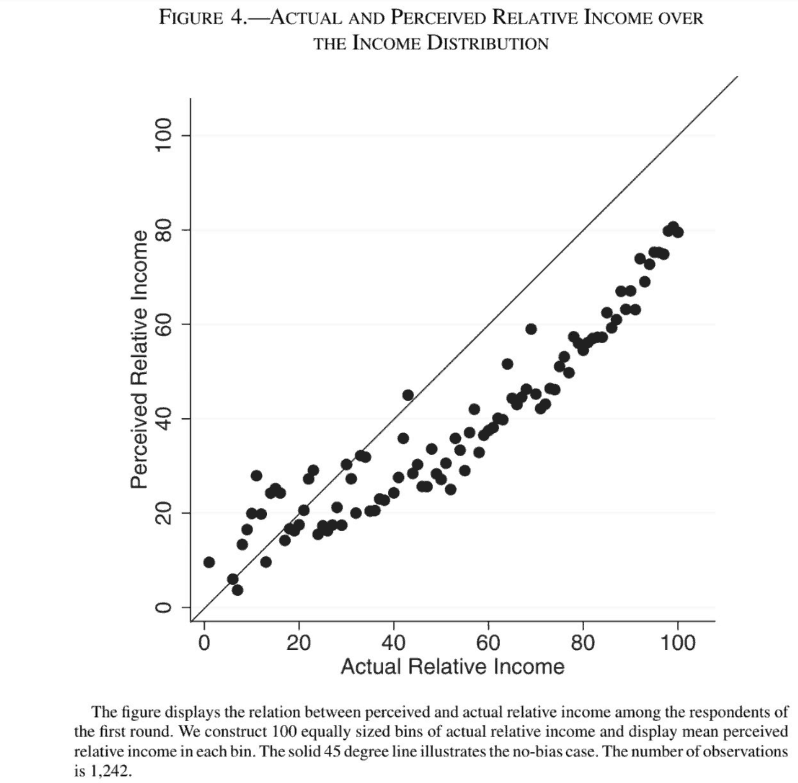

As the chart below, from this MIT Press article illustrates, most households in the upper half of the income spectrum (on average) don’t realize how well they have it:

Even households at the 90th percentile and above believe that they are in the 60th-80th percentile range. It’s like that article “Everyone is Getting Hilariously Rich and You’re Not” on repeat.

While this result might seem surprising at first glance, if you think about wealth perception as a network problem, it makes a lot of sense.

Matthew Jackson explained this concept well in The Human Network when discussing why most people feel less popular than their friends:

Have you ever had the impression that other people have many more friends than you? If you have, you are not alone. Our friends have more friends on average than a typical person in the population. This is the friendship paradox…

The friendship paradox is easy to understand. The most popular people appear on many other people’s friendship lists, while the people with very few friends appear on relatively few people’s lists. The people with many friends are overrepresented on people’s list of friends relative to their share in the population, while the people with few friends are underrepresented.

You can apply this same thinking within your social networks to illustrate why most people feel less rich than they actually are.

For example, you can probably think of at least one person who is wealthier than you are. Well, that wealthier person likely has some wealthier friends, so they can think of someone wealthier than themselves as well.

And if they can’t, then they can easily reference a celebrity (i.e. Gates, Bezos, etc.) who is.

If you extend this logic to its natural conclusion, you will realize that everyone (besides the world’s richest person) can point to someone else and say, “I’m not rich, they are rich.”

That’s how filthy rich billionaires like Blankfein can feel like they are just “well-to-do.”

Well, guess what? You probably don’t act all that different.

How do I know? Because you are likely far richer than you think.

For example, if your net worth is greater than $4,210, then you are wealthier than half of the world, according to the 2018 Credit Suisse Global Wealth Report.

And if your net worth exceeds $93,170, which is similar to the median net worth in the U.S., that puts you in the top 10% globally. I don’t know about you, but I would consider someone in the top 10% to be rich.

Let me guess…you disagree? You don’t think it’s fair to compare yourself with random people across the globe like rural farmers in the developing world?

Well guess what? Lloyd Blankfein probably doesn’t think it’s fair to compare himself with people like you and me either.

Yes, Blankfein’s claim of “not being rich” is objectively more outlandish than the claim that “being in the top 10% globally isn’t rich.” However, they are fundamentally the same argument. We are just splitting hairs.

After all, is the top 10% rich? The top 1%? The top 0.01%?

And at what aggregation level? Globally? Nationally? City-wide?

There is no right answer, because “being rich” is a relative concept. Always has been and always will be. And that relativity will be present throughout your life.

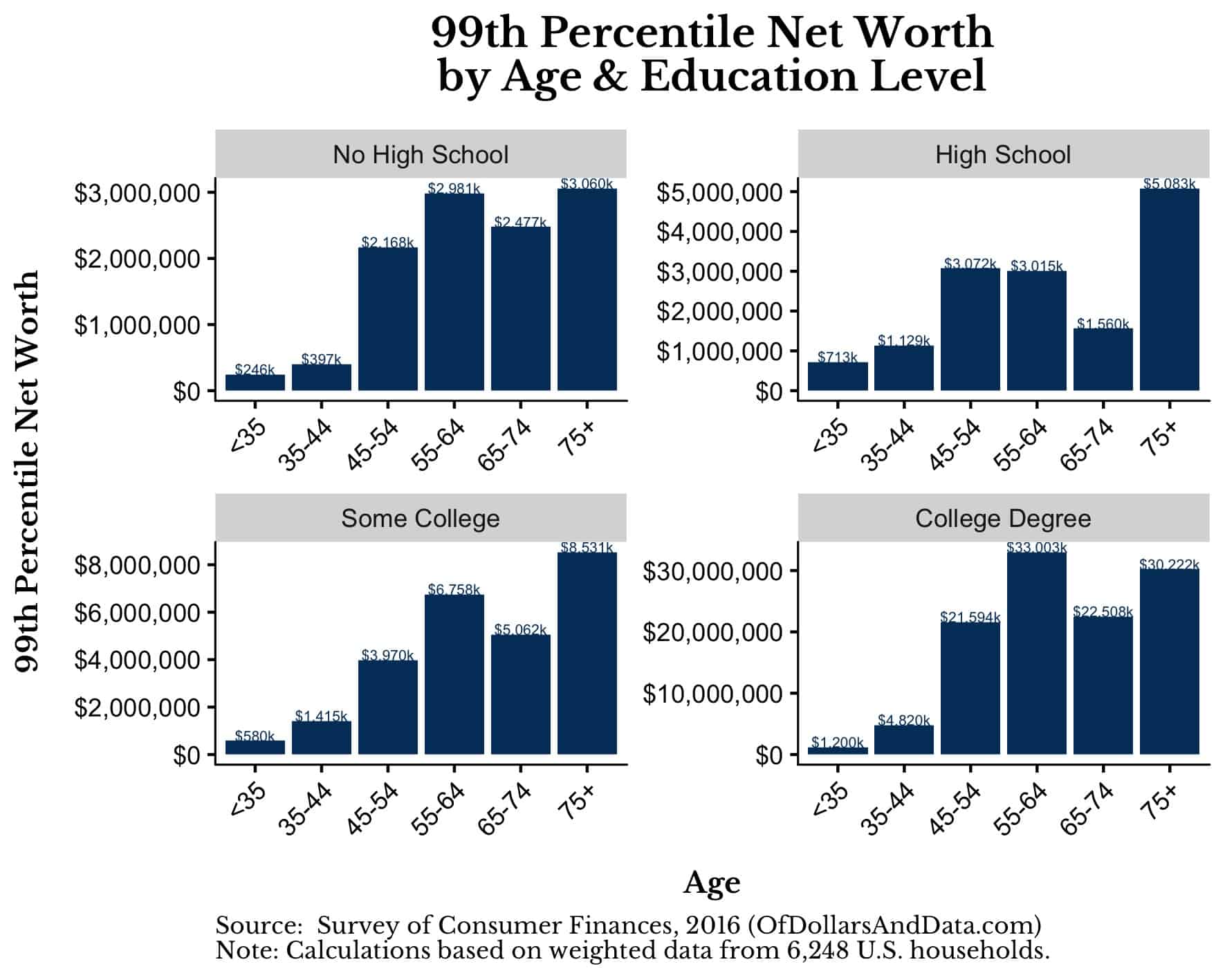

For example, you would need a net worth of $10.35 million to be in the top 1% of U.S. households. However, if you control for age and educational attainment, the top 1% varies from as little as $246,000 to as much as $33 million:

This is why when I ask, “Who feels rich really?” the answer is—no one.

Because you can always point to someone else who is doing better.

But, the trick is, not to forget all the people who could be pointing at you.

Thank you for reading!

If you liked this post, consider signing up for my newsletter.

This is post 180. Any code I have related to this post can be found here with the same numbering: https://github.com/nmaggiulli/of-dollars-and-data