He was preparing a fire inscription for an Israeli youth movement when he experienced the event that would change his life forever—the magnesium caught fire. Within seconds, a strong white light filled the room as flames, burning at a few thousand degrees Celsius, engulfed his body. In a state of confusion he almost tried to jump out the window (he was on the 4th floor of a building), but, instead, found a way to put out the fire with help from a friend. Though he was able to save his life, Dan Ariely would end up receiving third-degree burns on over 70% of his body.

In the aftermath of the accident, Dan would have to experience excruciating bandage removal treatments, from what was left of his charred skin, every day for a period of three years. During these painful treatments, Dan asked himself a question:

Was it better to have these bandages removed quickly (with the accompanying high intensity pain) or over a longer duration (with less intensity)?

After his recovery, Dan began doing experiments and came to a startling conclusion as told in his book Predictably Irrational (emphasis mine):

It turns out, I told the nurses and physicians, that people feel less pain if treatments (such as removing bandages in a bath) are carried out with lower intensity and longer duration than if the same goal is achieved through high intensity and a shorter duration. In other words, I would have suffered less if they had pulled the bandages off slowly rather than with their quick-pull method.

Dan’s story parallels an interesting psychological principle on how we remember events—we tend to focus on the most intense and the most recent parts of a memory when judging an experience—the peak and the end. This idea, formally called the peak-end rule, was based on work done by Barbara Fredrickson and Daniel Kahneman in 1993. As a simple example, imagine having the best tasting meal of your life, however, after heading home you get food poisoning for the next 3 days. Though the meal was incredible, you would probably remember it as a terrible experience because of the food poisoning.

For investors, the peak-end rule is incredibly important because it explains why we tend to remember moments of market trauma (high intensity) and the most recent market events (recency bias) over many others. As Jason Zweig perfectly summarizes in Your Money and Your Brain:

The more recently an event has occurred, or the more vivid our memory of something like it in the past, the more “available” an event will be in our minds—and the more probable it will seem to happen again.

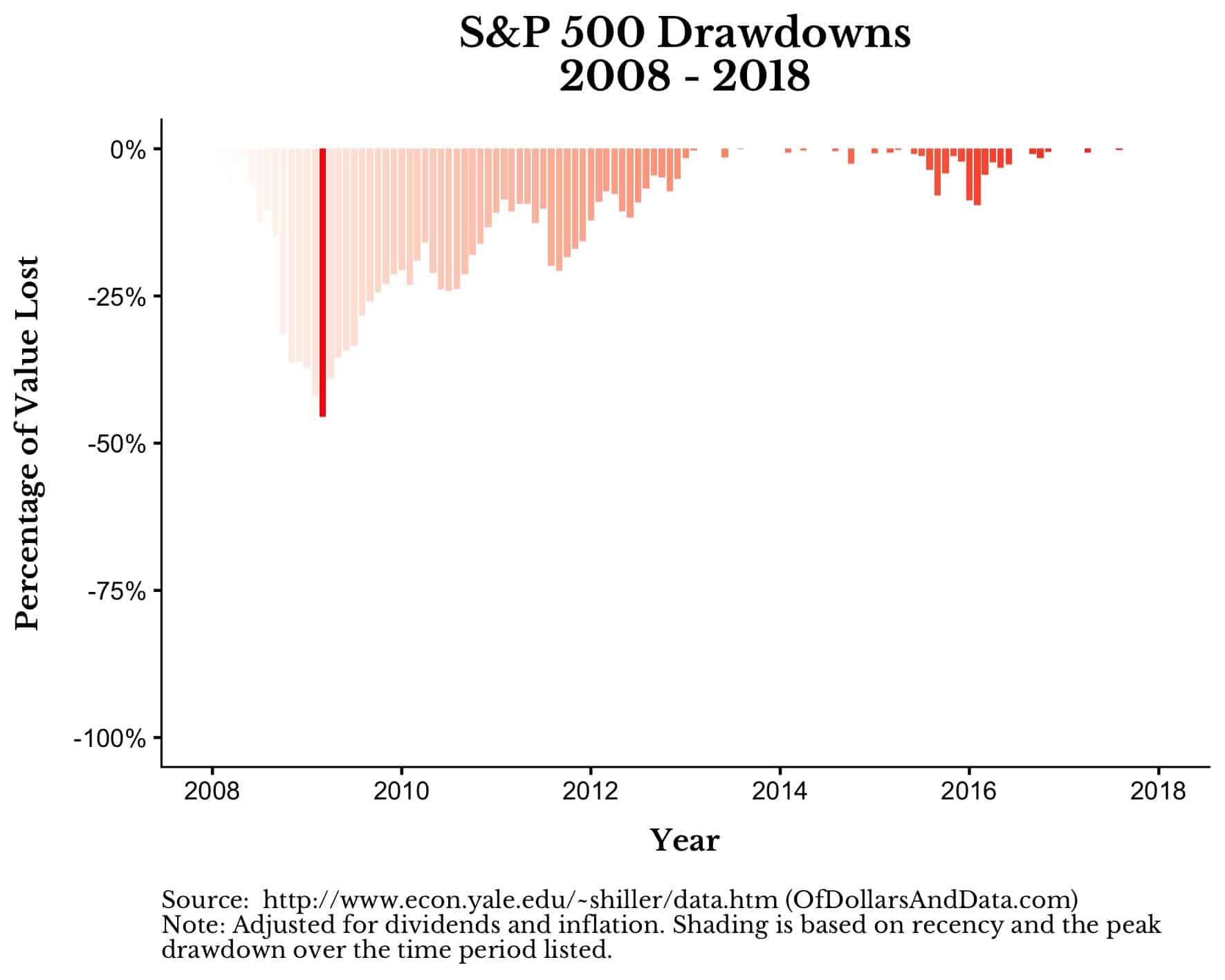

If we had to plot what this would look like visually, imagine the drawdowns for the S&P 500 over some 10 year time period. Now march forward in time and watch as most market history is “erased” from the investor’s psyche (this is recency bias). I have demonstrated this below by highlighting (i.e. making more red) the most recent and intense drawdowns in each 10 year period:

Though this visualization is imperfect, it illustrates how we tend to overweight the most recent information while also letting the most intense moments linger in our subconscious as well. This matters because, despite our privilege of knowledge, investors tend to collectively “forget” market history and succumb to the same forces of fear and greed again and again. This “forgetting” is either accidental or unavoidable since you cannot get the feeling of market history from looking at a chart or reading a book. This is why the peak and the end matters so much, it has to be experienced to be understood…

The Beginning Matters Too

While I think the peak-end rule is generally quite good at explaining how we remember market history, I do think there is more to the story—the beginning matters too. Your formative years in investing will be just as important as the most intense and recent years that you have experienced. For example, I have a bias against physical real estate because of what I saw my family go through in 2008 though I wasn’t investing at the time. In addition, because I did start investing in 2012 I have only seen the market head in an upward direction. It’s no wonder that I wrote a piece called Just Keep Buying and I consider myself an optimistic capitalist.

My beginnings have shaped who I am as an investor to a large degree and so have yours. Just imagine an investor in the 1930s who saw themselves lose 80%, then recover, and then lose 50% all within the same decade. They will remember markets far differently than you or I because of how they started.

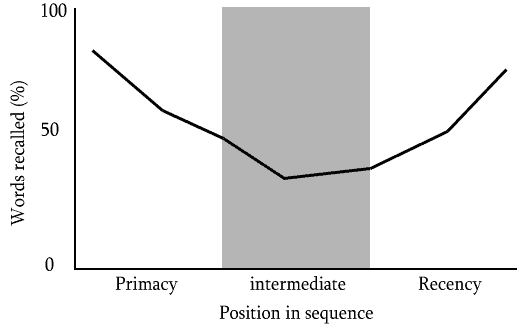

In fact, there is a psychological term for this: the serial-position effect. The serial-position effect states that people tend to remember the first things (primacy) and the last things (recency) in a list, but tend to forget the middle things. Visually the serial-position effect for recalling a list of words looks like this:

What’s even more interesting is that our brain uses the serial-position effect all of the time to remember information. For example, consider this sentence I put together where each word has the correct first and last letter with the middle letters scrambled:

You sluhod be albe to raed tihs snetnece tohguh amlsot ervey wrod is spleeld icorenlrcty

If you haven’t seen this before you are probably in a state of shock right now. It’s okay. Just breathe.

My point is that the serial-position effect and the peak-end rule together seem to be how we remember events as investors. This is important for you because it might help reveal where you could have biases. For example, I know I have a bias against physical real estate and I know that I am an optimistic capitalist. I mean, I once said on Twitter, “The bull market started in 1776,” so you can see where I stand on a lot of things.

The question is: what beginning, end, and peak market experiences do YOU have and how might they bias your investment decisions in the future? I wish I could help, but only you can answer that question. Until next time, remember the peak and the end and thank you for reading!

If you liked this post, consider signing up for my newsletter.

This is post 80. Any code I have related to this post can be found here with the same numbering: https://github.com/nmaggiulli/of-dollars-and-data