When I was 23 years old I told myself that I wanted to have half a million dollars by the age of 30. At that point in time I had less than $2,000 to my name. I chose $500,000 as my end goal after reading that Warren Buffett had $1 million by the time he was 30. Note that Buffett had his $1 million back in 1960, which would be $8.9 million today. Since I’m no Warren Buffett, I cut the goal in half and didn’t adjust it for inflation either.

Well, last weekend I turned 31 and my net worth still hasn’t hit half a million dollars. I came up short. How short? Far more than I would have wanted. But that’s not really important. As Dominic Toretto, Vin Diesel’s character in the The Fast and the Furious, once said:

It don’t matter if you win by an inch or a mile. Winning’s winning.

Well, losing is losing too, whether by one figure or six figures. But what makes this “loss” particularly unfortunate is that it occurred during a raging bull market. I can’t blame the S&P 500 for my shortcoming, only my own behavior.

Where did I slip up? Well, it wasn’t for a lack of trying. I’ve been working full time for over 8 years and have put in 10 hours a week on this blog for almost 4 years now. Though I didn’t really monetize this blog until this year, even if I had monetized earlier I still would have come up short.

I also don’t think I can blame my spending either. Though I could have traveled and dined out less often (experiences I thoroughly enjoyed), those purchases wouldn’t have moved the needle enough to make a difference.

But you know what would have made a difference? Making better decisions earlier in my career.

While many of my friends went off to big tech firms (i.e. Facebook, Amazon, Uber, etc.) and got that sweet, sweet equity compensation, I worked at the same consulting firm for six years where I was paid generously, but had no such upside. I didn’t realize how much I was missing out until it was a bit too late.

Now many of those friends are millionaires (or at least half millionaires) after exercising their stock options following the massive growth in tech valuations. It reminds me of this headline from the New York Times following the Bitcoin bull run at the end of 2017:

Yes, it’s easy to write my friends off as lucky (which is partially true), but I also know that’s just an excuse. Because I had many opportunities to board the big tech boat as it passed by, but I declined them all. And it’s not that I wanted to work in big tech specifically (I didn’t), but my mistake was not taking any career risk at all until I was 28 years old. Avoiding career risk early on seems like a foolish decision in hindsight.

As harsh as this sounds, I promise that I am not as hard on myself as it might seem. I know that I currently have a much better life than what I would’ve expected given my upbringing. In addition, I doubt I would have this blog in its current state had I joined a big tech company. So there’s that.

But more importantly, I know that even if I had reached my $500,000 goal, it likely wouldn’t have changed my life in any meaningful way. As I have written previously, affluence increases in steps, roughly by factors of 10 (i.e. logarithmically). This is why someone who increases their wealth from $10,000 to $100,000 will probably see a bigger life impact than someone going from $200,000 to $300,000. So even if I were to become a half millionaire tomorrow, it wouldn’t change a thing.

In addition, I understand how tone deaf it sounds when I complain about not reaching an exorbitant financial goal while many U.S. households struggle to make ends meet. But, as I have said many times before, wealth isn’t an absolute game, it’s a relative game. For better or for worse, I will compare myself relative to my own aspirations and my own peer group just like you will. I wish it wasn’t like this, but it is. You can argue with me all you want, however, overwhelming research suggests otherwise.

For example, in the book The Happiness Curve Jonathan Rauch describes how happiness in most people starts declining in the late twenties, bottoms at age fifty, and then increases after that. When plotted, lifetime happiness ends up looking like a U-curve (or a little smile).

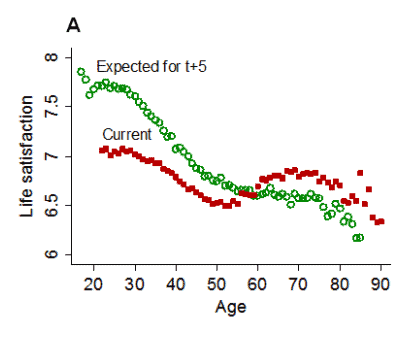

Visually, you can see this in empirical research from Hannes Schwandt, an economist and assistant professor at Northwestern University, when he plots the expected life satisfaction five years in the future by age and the actual life satisfaction at that same age:

Note how the “Current” life satisfaction forms the famous happiness U-curve from ages 25-70.

But why does happiness start to decline in the late twenties? Because, as people age, their lives usually fail to meet their high expectations. As Rauch states in The Happiness Curve:

Young people consistently overestimate their future life satisfaction. They make a whopping forecasting error, as nonrandom as it could be—as if you lived in Seattle and expected sunshine every day…Young adults in their twenties overestimate their future life satisfaction by about 10 percent on average. Over time, however, excessive optimism diminishes…People are not becoming depressed. They are becoming, well, realistic.

Look what happens in the fifties. The U curve begins swinging upward…For a good twenty years, every year brings not another dose of regret and disappointment, but another pleasant surprise.

This research explains why I am a bit bummed about not reaching the audacious financial goal I set for myself when I was 23 years old. However, it also explains why I was unlikely to reach that goal in the first place (i.e. it was probably too optimistic).

You may find this same pattern in your life too. You may have set your expectations rather high while you were young, only to be let down later. However, as the research suggests, this is completely normal. What’s also normal is lowering your expectations over time, probably too much, to the point where, as you head into old age, pleasant surprises will provide you with additional happiness. We begin our lives as growth stocks, but end our lives as value stocks.

The high expectations of youth (growth) eventually get replaced by lower expectations and upside surprises as you age (value). Of course, this is only on average. Everyone’s life is different with its own twists and turns. You don’t have to take the growth-to-value path like many others do.

For example, I don’t plan on taking this path because my expectations for myself have generally been increasing over time. Despite not reaching one of my early financial milestones, I am not deterred. Because I know that there are more days ahead and, therefore, more chances to push onward.

Yes, the research says that I will likely fail to reach my high expectations. But, sometimes, you can’t always listen to the research. Stay invested my friends.

Thank you for reading!

If you liked this post, consider signing up for my newsletter.

This is post 214. Any code I have related to this post can be found here with the same numbering: https://github.com/nmaggiulli/of-dollars-and-data