Which group of people (by age and sex) is least likely to die in the U.S. within the next year? For example, is it newborn girls? Teenage boys? Women in their thirties? Men in their fifties?

Before reading on, think about this for a second and take a guess.

All done?

The answer, according to the Social Security Administration’s actuarial life tables, is nine year old girls, followed up by 10 year old girls then 10 year old boys. Less than 1 in 10,000 in each group will die in the U.S. over the next year, which is the lowest of any age-sex combination in the data.

Why? Because 9-10 year old boys and girls are in the goldilocks zone of life. They are old enough to have decent immune systems (making them less frail than babies/toddlers) while still being young enough to not want to take risks like their older counterparts. Despite this, according to this 1999 data from National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), the most common cause of death among children 5-14 is accidents, followed by cancer then homicide.

I raise this point not to be grim, but to emphasize that when it comes to figuring out how to live longer, we may be focusing on the wrong things. As Charlie Songhurst said in an episode of Invest Like the Best:

One of the things I think that sort of is perhaps underestimated, is if you want to live forever, maybe don’t start thinking about studying centenarians, instead, work out how to not die of a DUI or drunk driving or anybody else smoking 20 cigarettes a day.

And to some extent, the same in entrepreneurship, is people spend a lot of time studying greatness. They don’t study failure. They study Mohammed Ali. They don’t study all the heavyweight boxers that faked out after losing that first match.

Songhurt’s idea is that studying negative outcomes can be just as useful, if not more useful, than studying positive ones.

We can take this idea and extend it to investing as well. So instead of asking, “How do investors succeed?” we can ask, “How do investors fail?” To that end I have compiled a list of the five most common causes of investor failure, and how to avoid them.

Too Much Leverage

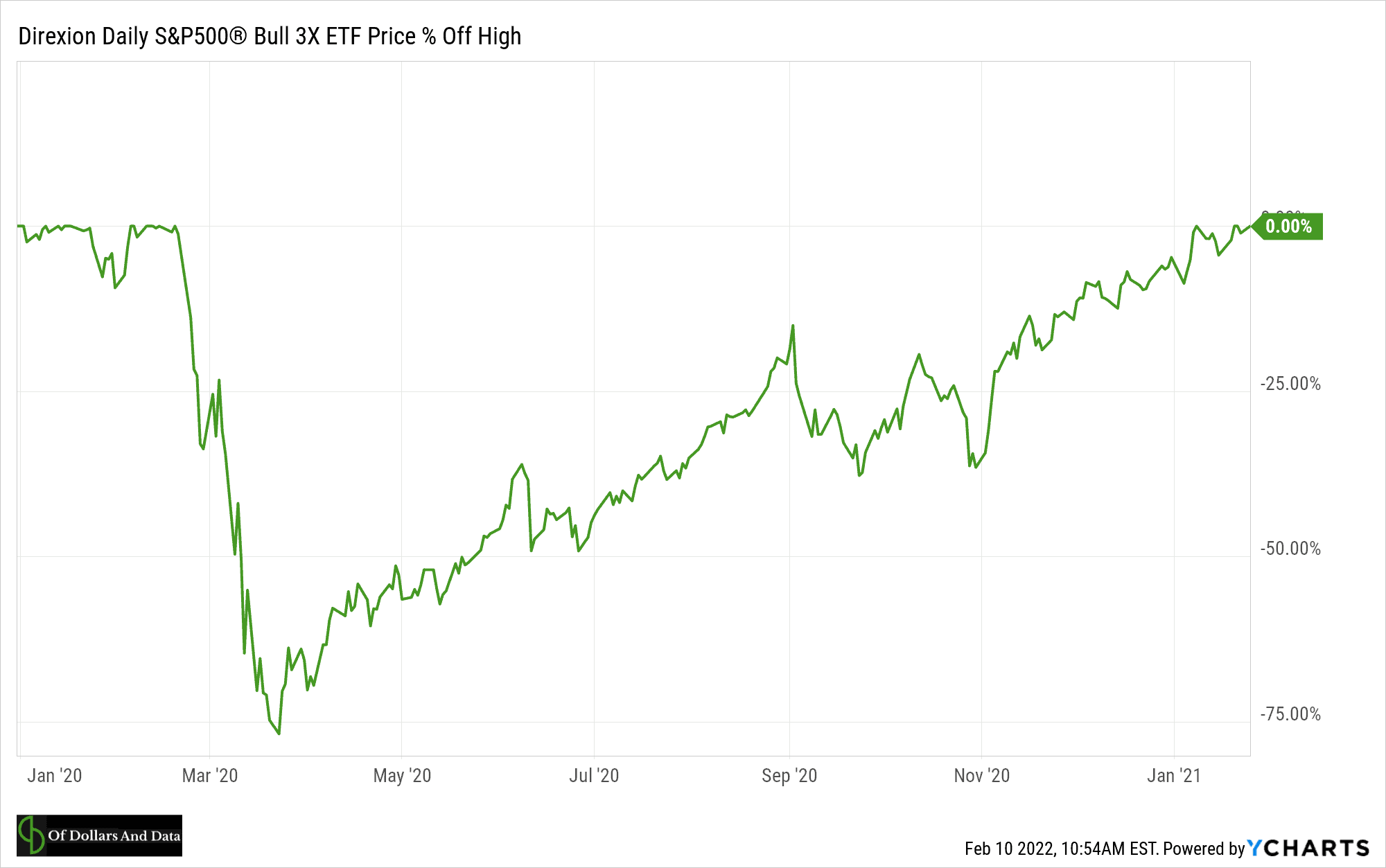

I’ve written on the dangers of leverage before, but a periodic reminder never hurts. Whether we are talking about the downfall of Long Term Capital Management (LTCM) or an unlucky bout volatility, too much leverage is an easy way to go for broke. Why can leverage be so disastrous for your returns? Because it takes any existing price swings and amplifies them. So a little decline becomes a big decline in a hurry. For example, a 3x long S&P 500 ETF would have declined by nearly 75% in March 2020, which is much worse than the 33% decline in the underlying index:

Of course, those that held on would’ve been rewarded during the recovery. However, if the crash had been much worse, it could’ve destroyed nearly all of your capital. It’s these rare, big declines that wipe out many investors.

So what should you do? Don’t borrow money and then invest it. And if you do, keep it to a minimum. After all, if Warren Buffett never levered his portfolio beyond 1.7-to-1, why should you?

Not Setting Aside Money For Taxes

Not setting aside money to pay capital gains taxes is a surefire way to derail your investing career and I have a story to prove it.

I have a friend who starting day trading crypto in early 2021 with $100,000. By year end he had grown his portfolio to $1.1 million, realizing about $1 million in short term gains along the way. Unfortunately, he never set aside any of these gains to pay the IRS as he rolled his money into new positions.

Well, as crypto crashed going into 2022, his portfolio plummeted to around $400,000. But guess what? He still owes the IRS $300,000 for his 2021 gains! So, after liquidating his portfolio, he would be left with ~$100,000. Right back to where he started. Ironic, I know.

Technically my friend is better off than where he started because he now has a $700,000 tax loss carry-forward that he can use to offset future gains. But, he’s one of the lucky ones.

What if my friend’s portfolio had crashed further and he had lost everything? He would still owe the $300,000 in taxes, but have no way of paying for it. This is the situation that some unfortunate traders find themselves in today.

Morale of the story: when you sell for a capital gain, always set aside some of it to pay your taxes.

Too Much Concentration

If not respecting the IRS doesn’t get you in trouble, not respecting diversification eventually will. Of all the ways in which investors fail, being overly concentrated is near the top of the list. Of course, I understand why investors do it. As the saying goes:

Concentration to get rich, but diversification to stay rich.

Yes, concentration is one of the few paths to extreme wealth, but it’s also one of the few paths to absolute ruin as well. History is riddled with examples of traders and business owners alike who went from riches to rags because they had all their eggs in one basket.

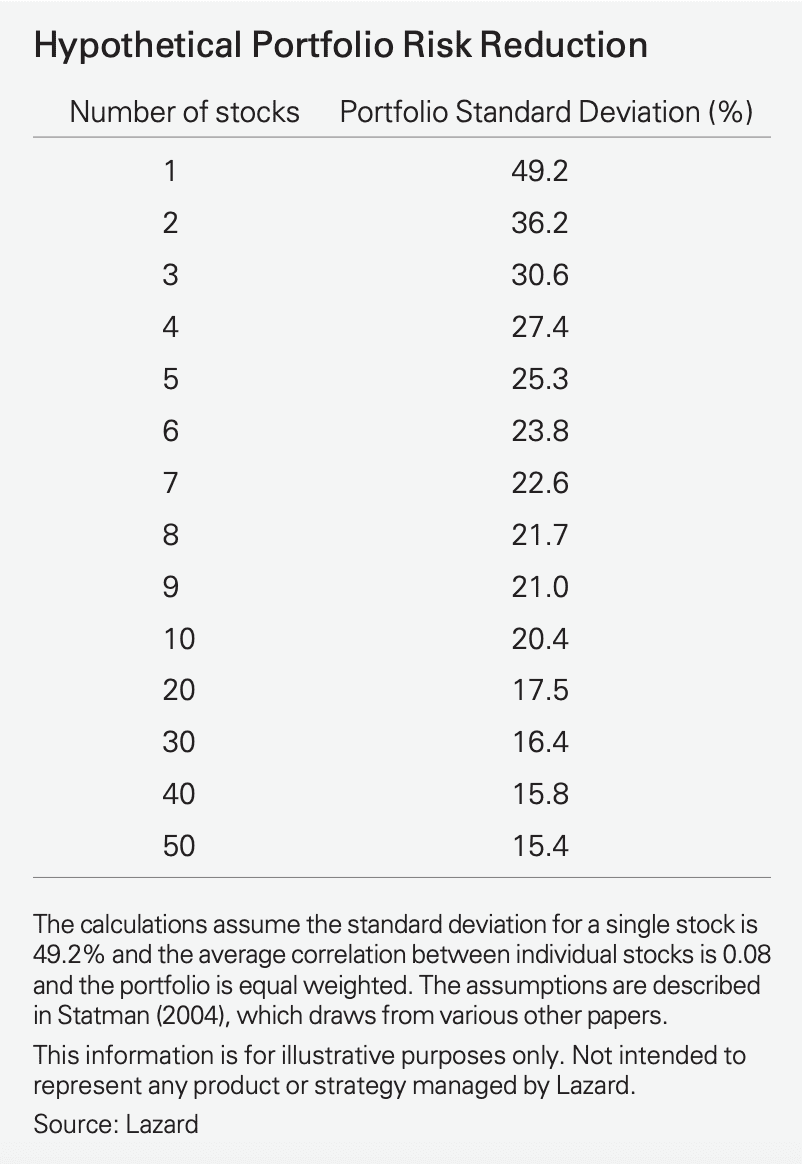

I’m not saying that you can never make concentrated bets, only that a little diversification can go a long way. For example, Lazard did a review on concentrated stock portfolios and found that increasing your portfolio from one stock to five stocks cut the portfolio’s standard deviation in half. As you can see in their table below, even the smallest amount of diversification can significantly reduce how much risk you are taking:

So if you use concentration to win the battle, make sure to use diversification to win the war.

All-or-Nothing Decisions

Similar to having too much concentration in your portfolio, making large all-or-nothing decisions with your investments is a recipe for disaster. Whether that means moving to 100% cash during a panic or going all-in on an asset that has recently collapsed in price, all-or-nothing decisions are usually very risky moves. Why?

Because all-or-nothing decisions tend to increase risk.

Even when you go all-in on a “risk-free” asset like cash, you are still increasing your risk, it’s just a different kind of risk. Because the risk of being 100% cash isn’t you losing money over the next month. No, the risk of being 100% cash is you losing money over the next year and beyond. As I have alluded to before, holding too much cash is the drug equivalent of cigarettes, not heroin.

So how do you combat the temptation to make these all-or-nothing decisions? You take a step back, you don’t trade while you’re emotional, and you stick to your long-term plan. That’s the only all-or-nothing decision that I will always support.

Investing What You Can’t Afford to Lose

Last but not least, many investors fail when they invest what they can’t afford to lose. Whether that means borrowing too much, not setting aside money for taxes, or going all-in on a risky bet, investing what you don’t have is a foolproof method for losing everything that you do have.

The problem with investing like this is the mismatch between the variable returns of your portfolio and the fixed costs of your lifestyle. In other words, though your gains are uncertain, your liabilities are guaranteed. I once stated that:

If you need to spend money and you can’t, that’s risk.

By this definition, investing what you can’t afford to lose might be the riskiest investment choice of all.

With that being said, if you want to be more successful as an investor, sometimes it’s good to know how to fail. Thank you for reading!

If you liked this post, consider signing up for my newsletter.

This is post 281. Any code I have related to this post can be found here with the same numbering: https://github.com/nmaggiulli/of-dollars-and-data