Last week Austen Allred started a huge debate on Twitter/X after tweeting:

Why isn’t the ideal investment strategy for 99% of people under the age of~45 just putting 100% of cash directly in the S&P 500?

This argument has more or less been made by the late Jack Bogle, Warren Buffett, and JL Collins in his bestselling book The Simple Path to Wealth.

But is it really that easy? Is a 100% U.S. stock portfolio the golden ticket to wealth for most people? Or are there significant drawbacks that warrant a closer look?

In this blog post I will explore these questions by examining US stock performance vs other asset classes and some of the behavioral challenges associated with owning a 100% U.S. stock portfolio. Let’s begin by looking at how often U.S. stocks outperform other asset classes.

How Often Do U.S. Stocks Outperform?

One of the key reasons why people recommend a 100% U.S. stock portfolio is because the performance in recent years has been incredible. In fact, over the last 10 years U.S. stocks have outperformed their international counterparts by about 7% per year.

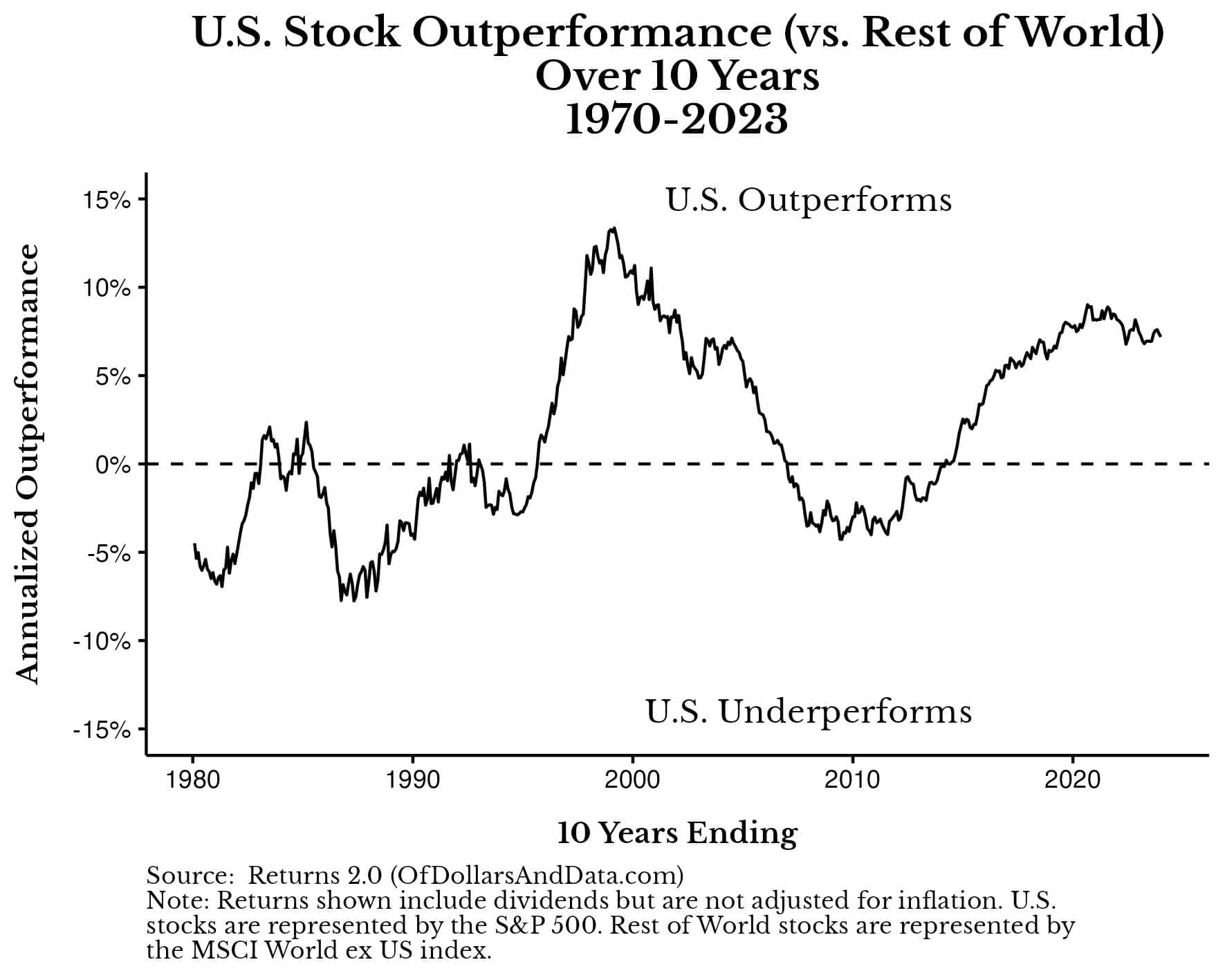

What about historically? Using data going back to 1970, U.S. stocks have outperformed international stocks in 54% of all rolling 10-year periods and in 80% of all rolling 20-year periods. As you can see, in the plot below, U.S. outperformance over a rolling 10-year period peaked during the height of the DotCom Bubble, fell during the Great Financial Crisis, and increased once again in recent years:

After looking at this plot you might argue that there’s no point in owning international stocks because they simply haven’t performed as well as U.S. stocks in the past. And, while this is technically true, a lot of this argument hinges on data from the most recent decade. When we control for this recency bias, U.S. stocks don’t look quite as impressive.

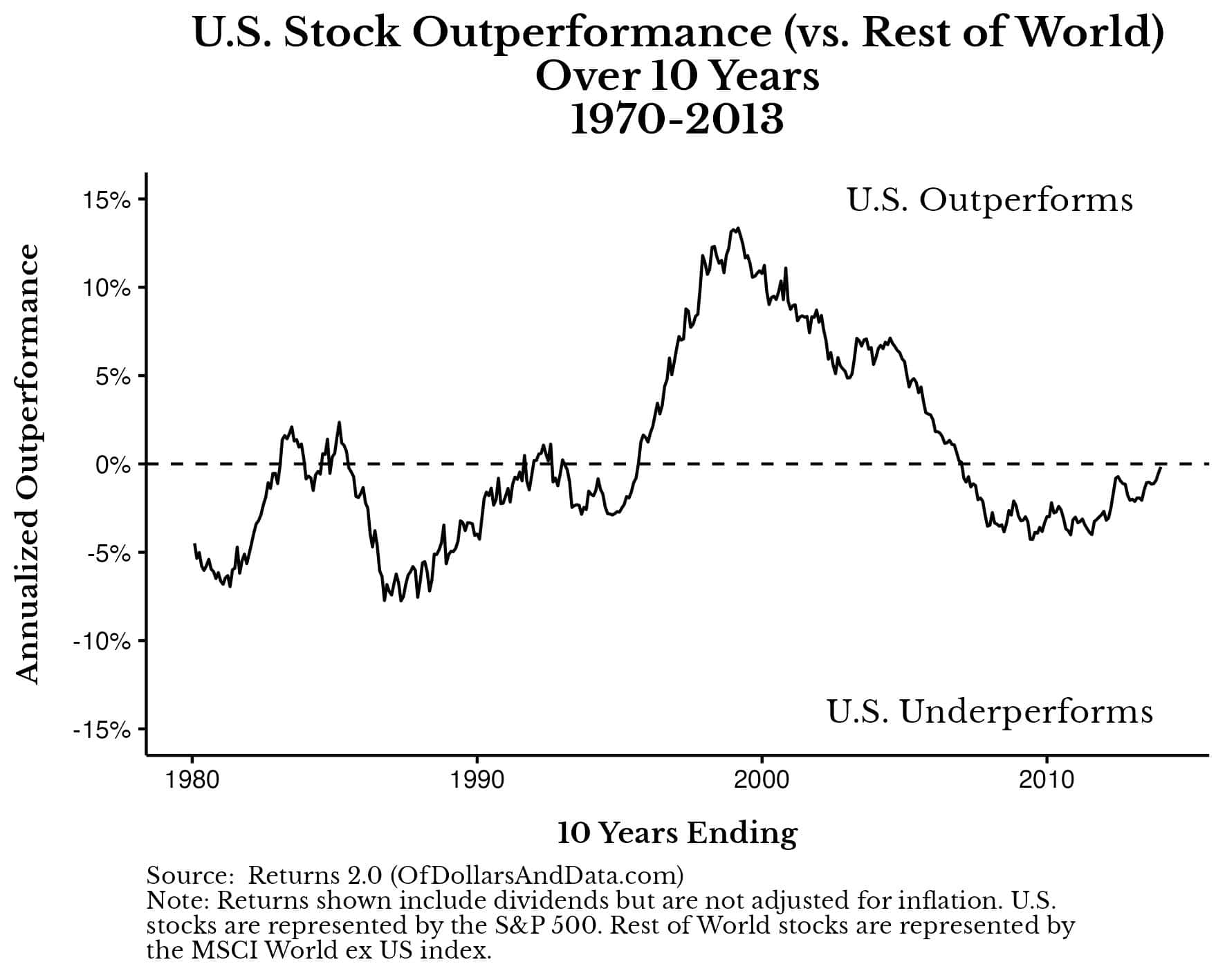

For example, if we had run this exact same analysis back in 2013 (which would’ve excluded the last 10 years), US stocks would have only outperformed international stocks in 41% of all rolling 10-year periods. As you can see in the plot below, from 1970-2013 U.S. stocks were more likely to underperform (than outperform) international stocks over a random 10-year window:

Now imagine looking at this plot back in 2013. What does it say to you? Does it say “U.S. stocks are superior to international stocks”? No, it doesn’t.

If anything, you could argue the opposite. After all, the only period in this data where U.S. stocks had sustained outperformance over international stocks was during the late 1990s to mid-2000s. This period coincides with the worst bubble in U.S. stock market history. Is it possible that this period of U.S. outperformance was merely a fluke caused by animal spirits gone awry? Of course.

This is why it was easy to argue for investing in international stocks over U.S. stocks a decade ago. Back then, whether U.S. stocks outperformed international stocks over a 10-year period was worst than a coin flip (41% success rate). But, today the tables have turned as U.S. stocks have pulled away from the rest of the world.

However, international stocks aren’t the only other asset class that U.S. stocks have outperformed. They’ve also outperformed U.S. bonds most of the time as well. Going back to 1926, a portfolio of U.S. stocks would have outperformed 5-Year U.S. Treasury Notes (“U.S. Bonds”) in 83% of all 10-year periods and nearly 99% of all 20-year periods.

Of course, I wouldn’t expect anyone to have a portfolio of 100% U.S. bonds. But, even when we compare the performance of a 100% U.S. stock portfolio to a diversified portfolio of say 80% U.S. stocks/20% U.S. bonds, the 100% U.S. stock one outperformed in 76% of all 10-year periods and in 86% of all 20-year periods.

This provides some evidence that owning some U.S. bonds can be beneficial during periods of weak U.S. stock performance. However, since those periods are rare, historically, owning U.S. bonds has detracted from long-term performance.

Outside of international stocks and U.S. bonds, there are many other asset classes that you would have to forgo as a 100% U.S. stock investor. For example, U.S. farmland had a total return of 9.0% per year from the 4th quarter of 1990 until the end of 2022 while also having a negative correlation with U.S. stocks throughout most of this time period. Though U.S. stocks outperformed farmland by about 1% per year during this time, investing in farmland would have provided you with great returns that were uncorrelated with traditional financial markets.

This is what you are giving up by being a 100% U.S. stock investor. You might argue that this doesn’t matter since U.S. stocks have generally outperformed most other asset classes in recent decades. That is true, however, there is nothing that says this will hold in the future.

Now that we’ve analyzed how often U.S. stocks tend to outperform other asset classes, let’s discuss whether U.S. stocks by themselves are diversified enough.

Are U.S. Stocks Diversified Enough?

One of the other arguments put forth by U.S. stock only investors is that you don’t need to own international stocks because U.S. stocks are already diversified through their exposure to foreign markets. After all, U.S. companies sell their products and services to people all over the world. In fact, according to Global X, “roughly 40% of S&P 500 revenues are generated outside of the U.S.” While U.S. stocks do have exposure to foreign markets, I think this argument misses a bigger point about what it means to own a 100% U.S. stock portfolio.

Typically, when you invest in the companies of a foreign stock market, you are implicitly making a bet on the sectors that dominate that market. For example, if you owned an index of Norwegian stocks, you would basically be betting on their energy sector (i.e. Oil & Gas). If you owned a basket of South Korean stocks, you would be making a bet on their consumer electronics/manufacturing sector (e.g. Samsung), and so forth.

Well, the same thing is true when you only buy U.S. stocks. Though the U.S. stock market is far more diversified than any other stock market on Earth, investing 100% of your portfolio into U.S. stocks is inherently tilting your portfolio toward the U.S. technology sector.

Currently, the U.S. technology sector has a market capitalization of around $14 trillion, representing 26% of the value of the U.S. stock market. And while 26% may not sound like a lot, this 26% drives a lot of the sentiment in the rest of the U.S. stock market. This is why FAANG and the Magnificent 7 have been so popular with investors in recent years and why there is no similarly popular group of stocks outside of the U.S. tech sector.

So while betting on U.S. tech companies would have worked out great in the 1990s (leading up to the DotCom Bubble) or over the last decade, you have to ask yourself whether this is the kind of exposure you want in your portfolio going forward.

There’s no right answer to this question. I own international stocks because I want to reduce my exposure to U.S. tech companies and increase my exposure to the companies found throughout the rest of the world. This strategy has underperformed over the last decade and may underperform over the next decade, but that’s fine by me. Though I would rather not underperform, I also know that I can still reach my financial goals if I do.

Now that we’ve discussed what investing in a 100% U.S. stock portfolio actually means, let’s examine some of the behavioral challenges of owning this portfolio.

Is it Easy to Hold 100% U.S. Stocks?

Even if we ignore the possibility of underperformance and the technology sector tilt that a 100% U.S. stock portfolio entails, we must also address the behavioral difficulties associated with owning only U.S. stocks. While the data demonstrates that U.S. stocks haven’t lost money on a total return basis over any 30-year period going back to 1926, there’s a big difference between talking about investing in a 100% U.S. stock portfolio and actually doing it.

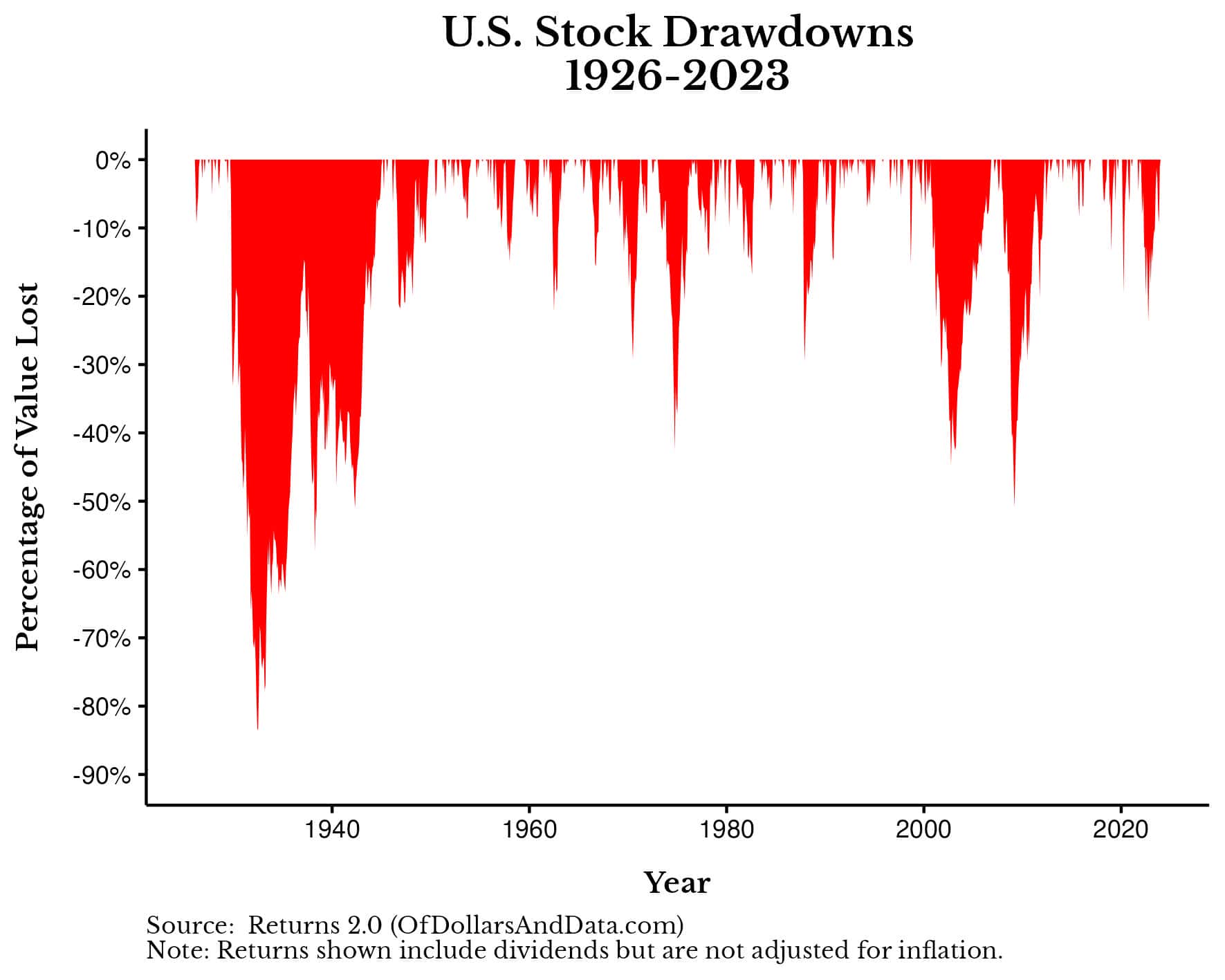

As the plot below demonstrates, there have been multiple periods throughout history where U.S. stocks were cut in half (or worse):

While it’s easy to look back on these times now and say “if you had just held on or kept buying, you would’ve made money,” this wasn’t so obvious while these drawdowns were happening. You have to realize that we have what I like to call the privilege of knowledge—we know things today that our ancestors didn’t know in the past.

This is why Austen Allred can ask, “Why isn’t the ideal investment strategy for 99% of people under the age of~45 just putting 100% of cash directly in the S&P 500?” Because he knows market history.

But, imagine all the people that take this advice without knowing market history. How might they react when stocks fall by 30% and then follow it up by falling another 30%? Some people will be okay with this, but others, who didn’t realize what they were getting themselves into, won’t be.

This is my primary concern with recommending a 100% U.S. stock portfolio to the typical person. Unless you can also educate them about market history and the risks they are taking with this portfolio, they may not stick with the strategy. And if they don’t stick with the strategy, then they won’t realize the performance.

So while it’s easy to say everyone should own 100% U.S. stocks because it will make them richer in the long run, this is only true if they don’t bail on it at the wrong time. When the going gets tough they have to stay invested or else they could end up far worse off than if they had just invested in a more diversified, lower risk portfolio (that they could stick with).

Unfortunately, I haven’t seen much data on what kinds of portfolios people are more or less likely to stick with. However, I have heard my fair share of anecdotes about people “giving up on the stock market” after losing too much money. If these people had been better educated or more diversified, maybe they wouldn’t have come to such a dramatic conclusion.

Now that we’ve addressed the behavioral challenges of owning a 100% U.S. stock portfolio, let’s wrap things up by considering the practical implications for everyday investors.

The Bottom Line

Putting the behavioral difficulties aside, owning a portfolio of 100% U.S. stocks isn’t the worst option out there. In fact, it’s a better strategy than what many retail investors do when they attempt to beat the market. Trying to pick the best stocks or trying to find the perfect time to invest are two such strategies that are doomed to fail in comparison to owning a U.S. stock index.

However, a 100% U.S. stock portfolio comes with its own set of risks. Not only will this strategy underperform at some point (possibly significantly so), but it also amplifies your exposure to the technology sector (an area where U.S. companies have dominated in recent decades). While you won’t catch me owning a 100% U.S. stock portfolio for these reasons, I don’t think anything less of anyone who does.

Nevertheless, this entire discussion misses a bigger point. Ultimately, your ability to reach your financial goals has less to do with your asset allocation and more to do with your career, your financial behavior, and your desired lifestyle. If an all-in U.S. stock portfolio can get you where you want to go, that’s great. But, such a portfolio isn’t necessary for everyone.

So let’s try to embrace the fact that there is no right portfolio and that what works for one person may not work for another. This is why “99% of people” can’t (and shouldn’t) use the same investment strategy, even if it seems optimal. Because no such strategy exists.

With that being said, happy investing and thank you for reading!

If you liked this post, consider signing up for my newsletter.

This is post 380. Any code I have related to this post can be found here with the same numbering: https://github.com/nmaggiulli/of-dollars-and-data